Railing Against the Elements

With careful detailing and proper flashing, exterior woodwork should last for decades.

Synopsis: Called upon to rebuild so many porch railings exposed to the weather of New York’s Hudson Valley, the author examines why so many of them fail. He looks in particular at a railing system on a flat roof and offers suggestions for construction details that will preserve the structure. A sidebar explains how to space balusters evenly.

The moist climate of New York’s Hudson Valley isn’t exactly ideal for carpenters like myself. We have muggy summers, slushy winters and three months of rain in between. As we struggle through weeks of unremitting precipitation with fogged-up levels and wet chalklines, there is but one consolation: come April, a billion fungal spores will bloom, reaching into every water-logged mudsill, fascia and doorstep. That means a guaranteed crop of rot-repair jobs in the coming season.

Of all the woodwork exposed to the elements, none is so vulnerable as the white pine porch railing. With the right combination of faulty detailing and wind-driven rain, a railing can be reduced to shredded wheat in about eight years. I typically rebuild several of these railings each year. In this article I’ll describe one such project.

Getting organized

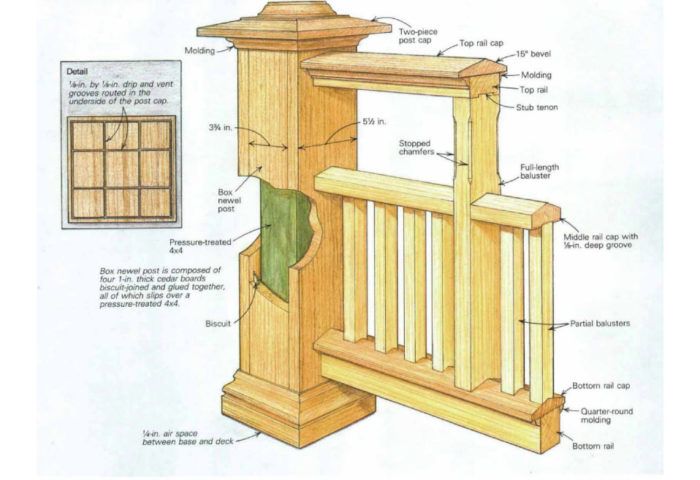

A railing around the flat roof of a garage had rotted out, and the owner asked me to build a new one. This wasn’t a deck that was used, so the railing was decorative rather than functional, and one of my worries was installing the new railing without making the roof leak (more about that later). On a house across town, my customer had spotted a railing that he liked and asked if I could reproduce it. I said I could and took down the address.

Before leaving the job site, I made a list of the rail sections I would be replacing, their lengths and the number of posts I would need. Later that afternoon I found the house with the railing my customer liked, strolled up the walk and began jotting down measurements. The family dog objected strenuously to my presence, but no one called the police.

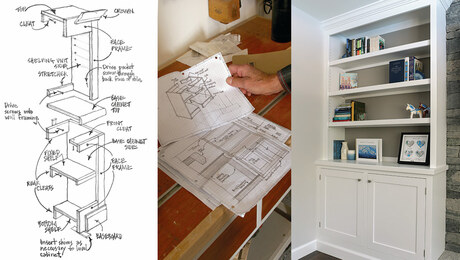

Back at the shop I drew a full-scale section of the railing and a partial elevation showing the repeating elements. The next bit of work was to make layout sticks (or rods) showing the baluster spacing for the different rail sections. This would tell me the exact number of partial- and full-length balusters that I would need.

The right wood

I’m fortunate to have a good supplier who specializes in boat lumber. He carries premium grades of redwood, cedar, cypress and Honduras mahogany, all of which resist decay well. I used cypress for the rails and balusters because it’s less expensive and because the rough stock is a little thicker than the others. Cypress is mostly flatsawn from small trees, though, and the grain tends to lift if the wood isn’t painted immediately.

Much of the Western red cedar at this yard is vertical grain — the annual rings run perpendicular to the face — and hence inherently stable. I typically use it for wider pieces where cupping could be a problem. Square caps on posts fit this description because they are so short in length. They should always be made from vertical-grain material or they’ll curl in the sun like potato chips.

For this job I bought 2-in. thick cypress for the rails and balusters, 5/4 red cedar for the rail caps and post caps, and 1-in. cedar boards for the box newel posts.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Shingle Ripper

Roof Jacks

Ladder Stand Off