Carpentry Ethics

Professional framer Larry Haun contemplates the balance between doing a "good job" and saving time and money.

I have some questions that maybe you can help me understand. They mainly have to do with my own work ethic and a few observations from building houses for more than 60 years. Maybe they will be food for thought for some of you.

A tale of two builders

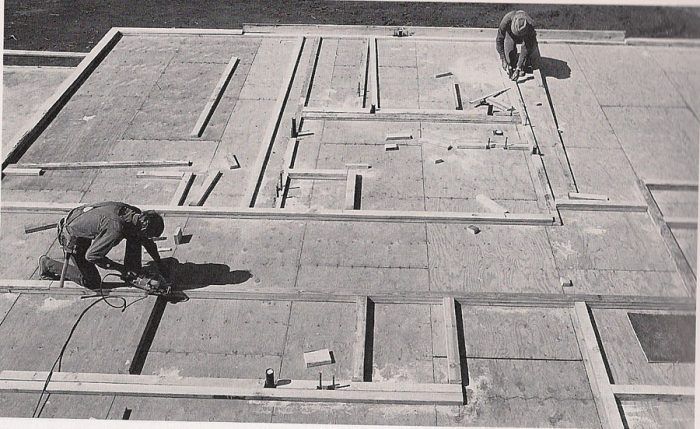

Let me start with a story. Back in the early 1980s, we were building a spec house in an exclusive canyon in the Los Angeles area. It happened that on the lot next door, a young builder named Tom was framing another spec house. We started working on the house frame on about the same day. Both he and I were building with one helper. By the time Tom had his house frame completed, the house we were working on was shingled, the walls were covered with stucco, and all the mechanical work (plumbing, electrical, heating) was awaiting inspection so that we could drywall inside. The final result of all this was that Tom ran out of money from the construction loan before completing his project. He had to turn the incomplete building back to the bank while we completed ours, sold it, and made a profit.

So why this disparity between these two similar houses? The main difference between us was that Tom and his helper were building furniture and we were production-framing a house. Every 2x block in his house was cut to perfection, every joint was clean and tight, and everything was framed to within 1/16-in. tolerance. Both houses were properly braced and built square, straight, and plumb; they were structurally sound. Both frames were then covered with drywall on the inside and stucco on the outside. Both houses should last for a long, long time. Is not the main difference that one cost much less to build?

So here is one of my questions: How do we build to ensure that customers get a quality home at the most reasonable cost and that we leave behind work we can be proud of?

I don’t want to take on some of the larger ethical issues we carpenters and builders face: creating construction waste, using certified wood, working with sustainable materials, or working with endangered wood species. And I don’t want to write about obvious ethical shortcomings. Cheating is cheating! Using inferior materials or doing sloppy work is not OK in any of our books. During the 1950s when I was framing on the tracts, every 1200-sq.-ft. house had a brick fireplace. To make his work easier and to make more money, one bricklayer I knew would cheat by cutting off the 20-ft.-long vertical steel rebar that bricks and flues were laid around. In place of the long rods tied into the foundation, he used a 4-ft. piece of rebar in each corner of the fireplace and pulled the bars up as he laid brick. If a building inspector happened on the job, he or she could see that the fireplace had the code-required steel bars in it.

A further question: Do I, as a carpenter, have any obligation to learn about and use new tools or methods of building if this will reduce the cost to a homeowner?

I go back to the revolution in methods, tools, and materials that took place in the early 1950s in Los Angeles as we changed from building one house at a time to building 500 in a row. We needed thousands of houses after the Great Depression and WWII, which demanded that we change our way of building. What we encountered in those days was substantial resistance from those who had been building differently for many generations. I have had people tell me out on the job site, “This is the way my father taught me to build, and it worked well for him. So why should I change?” I am not saying the old ways were wrong—just slow and outdated.

Technology improved efficiency

The methods we developed in the 1950s meant that we could build houses much faster without reducing the quality and without working harder. We called it “production-framing.” What was fascinating to me is that other carpenters across the country took forever to pick up on these methods. Whether we are building a tract house or a custom mansion, production-framing allows us to do it faster, costing everyone less money. This is the main reason I wrote the book The Very Efficient Carpenter, which was published in 1990. This book and accompanying videos are on production-framing.

Production-framing is actually quite simple. It is like working on an auto assembly line. On-the-line workers don’t install one tire on an auto, then the rear-view mirror, and then go back and install another tire. With production carpentry, everything is finished as complete as it can be before we move on to the next construction project. Pretty simple.

Take plating for walls, for example. When I started framing, we would snap a chalkline for a wall position on the floor, lay it out, build it, and then do the same for the next wall. This way works, but it is time-consuming, and someone has to pay the extra cost. We learned to snap chalklines for all wall lines, lay down all plates, do all detailing of studs and headers, and then start building walls. Am I right on this?

There are many other examples of production-framing: learning to cut square without using a square, marking foundation-bolt drill holes on a sill by using a simple tool, using a stud-layout stick (which saves time and materials), cutting multiples rather than one piece of wood at a time, not working to 1/16-in. or even 1/4-in. tolerances.

Cutting tolerances: I have seen framers work to cut their double top plate (cap plate) to the exact length, only to find that the plate of an intersecting wall won’t quite fit into the gap. Then we either have to bring the wall back down or jump up on a ladder and cut the gap wider, often dulling a saw blade in the process. Making the gap at an intersecting wall a bit wider does not lesson the structural integrity of a wall, and intersecting walls fit into the gap easily.

What one person thinks is sloppy, another sees as “just right”

None of these examples (and there are many more) cause us to work harder or faster. None of them damage in any way the quality of the building. All of them save time and therefore money. So the question is: What is our responsibility as carpenters, to ourselves and the people we build for, to upgrade our knowledge, methods, and tools to build quality homes at prices people can afford?

My experience is that most of us, including carpenters, resist change. I know I do. We have a tendency to follow conventional wisdom and to build like it has always been done. It is not always easy to be free from fixed mind. What is important, in my view, is that our unwillingness to change doesn’t mean that others have to pay extra for how we build. Does this make sense?

I end by saying that I am grateful for the workshops put on by people like Mike Guertin, Rick Arnold, Gary Katz, Fine Homebuilding magazine, and others. They help to bring us up to speed.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Reliable Crimp Connectors

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Affordable IR Camera

View Comments

Larry, this article smacks me with a couple of impressions:

For one, you only really discuss rough framing and secondly you never really discuss the fact that we all have differing opinions of what is "right".

I understand that the idea of "production framing" is about speed. The job boss on the crew I worked on would constantly yell "Elbows and @$$holes!!" to move us faster. But as I progressed in my career and found myself at one point as a custom trim carpenter then finally as a remodeler, I find that speed takes a backseat to quality. And by 'quality' I don't just mean quality of workmanship. Sometimes it is quality of service, that is working with the homeowner and making him feel like he is getting what he paid for. In the framing aspect which you are steeped, this may mean keeping it tighter, cleaner, and square while at the same time keeping the client happy, well informed, and welcomed on-site. Maybe that's just the difference between 'production' and 'quality'... your client is more or less faceless while mine is an added directive at each phase of construction.

I should forewarn anyone who has ever read my words or worked with me that over engineering is one of my pet peeves. So much so that after nearly a decade working in the field I went back to college and got my own degree in architecture so that I could learn the scoop on building science as well as perform any necessary structural calculations. This was due to encounters with so many archys and builders who - plain to say - didn't really know what they were doing, but usually assumed they were doing it "right". We've all seen 'hack jobs', but rarely will anyone admit they have any of their own out there. But in reality we ALL have hack jobs somewhere in the world - some of us are doing hack jobs thinking that they are 'top notch' or at the least 'good enough'.

Almost as bad is the over the top job........ of which the pages of FHB is RIPE! Many FHB types boast about their 'code plus' and 'belt & suspenders' approach to construction while not always considering the financial injustice they may be inflicting on their clients. Then they often go about boasting about their approach - some going so far as to use it as their sales pitch. To me, going so far above and beyond is just a sign of ignorance and laziness - that is too lazy to perform calculations and too ignorant to know what to calculate. The calculations may be applied to traditionally calculated items like beams, stud placement, and panel thicknesses or to more technical areas like flashing procedure, insulation methodology, and cladding details. Knowing when enough is enough shows experience and forethought but layering flashing 10 deep "just in case" may just show ignorance and is not really doing the client any favors.

I feel like my experience a remodeler gives me better insight towards these issues and my education only goes to back up that insight. Being a remodeler has allowed me to see what REALLY works and what can go horribly wrong in the construction of houses. Some of my jobs are poster children for the term "hack job" sometimes to the point of being dangerous, but more often just plain curious (as in "what the heck was this guy even thinking?"). But more appropriately, being experienced in the remodeling industry has allowed me to truly know what is meant by the term "fine homebuilding" and I think that is something that is often lost in the pages of the magazine.

So, the simple answer to your question is - We must only make homeowners happy. Some use over engineering, some use low cost. Others use high technology while still others rely on the idea of "hand built/old world quality". One carpenter is only concerned about finishing a house fast and selling it while another wishes to build a house that will last for centuries. You may say "be more efficient" but sometimes the codes limit that efficiency. The funny thing is that while we have legal answers to what is "wrong" we don't have any clear cut method to prove what is "right" and therefor no good way to determine what is proper "carpentry ethics".

Maybe someday I will be able to go back to school and get my "Master's in Carpentry" then I will have a better answer for you.

DC

Dreamcatcher,

Thanks for your considered comment. That is what I was hoping for---comments that open up this discussion on the "ethics of carpentry." Larry Haun

Larry, I started in construction in the late seventies. I was taught the "production" way of framing. I worked with and for builders and developers for some years before moving out on my own. I would say that it would be in a contractors best interest to find as many , fast, efficient, most productive way of doing a specific project. If it was for the only reason as to make money. Let's be honest with ourselves, that is the bottom line. I understand the "love of it" and the "feeling good of doing the job". But, the fact of the matter is that we all need to get paid. And if I can find a more efficient, time saving way of doing a job. Then I will adopt that way. I am a carpenter/ business owner, so I am looking for any advantage over my competitor. If I can cut man hours off a job, in-turn save some money which I can pass along to my "bid". I just may get that new job, and in-turn get paid.

I am all for one to do a quality job, no doubt. I can not afford poor quality. As for new technology, well I am a little old school on that. I prefer to take a wait and see attitude. I have been proven right on several "new" items that came out over the years, that ended in disaster for those contractors that jumped on board as soon as the product came out.

Overall, I am all for one in learning new tricks. Watching others work and picking up some alternative ways of doing tasks. As long as it does't include cheating, stealing or lying. Be honest and fair with clients, and speak up when it is needed. I agree with dreamcatcher, the overbuilding is a big expensive problem. And unfortunately, the architects/engineers just keep adding more and more unneeded bulk to the project. Which drives up my bid and the clients cost. So now, if I see something that I know is not needed, I say something. Keep up the good work.

I believe Larry is a legend in his own mind. Of course framing cannot be done like furniture; framing lumber is not flat and square. Left in the California sun and low humidity the studs on the outside of the stack are drier than those in the center. Short pieces dry more than long pieces. Go into any house and find four walls that are square to each other, usually can't be done. Thanks Larry. Can't lay hardwood flooring parallel to the length of the room without having a problem covering the gap along one wal? Thanks Larry. The bricklayer cut off the rebar and faked it to get past inspection and you didn't tell anyone; thanks Larry.

Doors don't hang sqaure have to be cut off at odd angles? Thanks Larry; had to get it done faster so I can get paid.

In my occupation it is common to hear those who shortcut their clients say "I've never had anyone complain", or "I've never had any problems." When you expect little it is easy to overlook multiple errors in performance. The American consumer is so poorly educated and so misled by mass media they think the status of the builder is the key to quality. The guys next door who didn't get the job "finished" and had to let the bank take over probably built something Larry couldn't, not didn't, couldn't.

The only key to quality is commitment. Applied with innovation and intelligence work of all kinds can be accomplished faster, as well and with fewer remakes. Cutting corners like faking the rebar in the chimmney, knowing about the practice and keeping quiet is the antithesis to eqaul quality and efficiency. Thanks Larry, you revealed yourself.

Dear Folks,

Thanks again for the thoughtful comments. Maybe I can add a bit to the ethics issue. There is seldom if ever any excuse for an unsquare rooms that I know of. Whether we work with production methods or methods from long ago---square is square. There are, by the way, people who learn production medthods and do lousy work. To me that is not ethical.

In ther 50s, I worked three years as a trim carpenter. I was started out hanging doors by the forman. I was expected, at that time, to hang at least eight doors a day. Several years later the three Schaffer brothers were hanging 60 to 80 doors a day (with a helper--- on the tracts and in larger commercial buildings) doing a much better job than I did with my hand tools. They had developed production methods for trim carpentry that I needed to learn. Gary Katz knew these brothers and learned from them. I think he even wrote an article in FHB showing a few of their methods. The brothers made good money for themselves and gave their customers quality work. Larry Haun

Hi Larry when you say the brothers hung 80 doors in a day, does that include fitting locks, handles etc or just swinging the doors?

Chapeli,

First of all, it means that each brother could hang 60 to 80 doors a day. What it meant for each door----scribing, fitting, cutting to length, drilling for lock and deadbolt when necessary, and hanging in the opening.

I knew Al Schaeffer the best. He was a master. What they did to speed production was develop tools to hold the door in place while being scribed, a door bench that allowed them easy access to power tools, marks on the bench so they didn't have to use a measuring tape to locate where to drill for lockset, and on.

If you are hanging doors, I would encourage you to check out the article I wrote in about 1989 on setting jambs and hanging doors and also one by Gary Katz on the same subject -- both are in FHB archives.

This is an ethical question----can we learn new ways to do our work that will allow us to hang a door faster----without reducing quality and costing our customers less money?

There are many other ethical questions.....that is just one.

Thanks for the question. Larry

Both Carver and AmazingGrace put forth some good inclusions towards the subject.

That first line wrote by carver, "I believe Larry is a legend in his own mind" while a bit callous does carry on the point I was attempting to make.... The majority of carpenters think they are THE BEST. Nobody will readily admit to being a hack and most won't admit to intentionally cutting corners.

But, as AmazingGrace wrote, "If I can cut man hours off a job, in-turn save some money which I can pass along to my bid..." which is true of most industries. Sometimes you can 'strategically' reduce the quality of a product but still have an outcome that will pass quality standards - and perform flawlessly 98% of the time. This means the customer is happy 98% of the time unless circumstances go awry and that 2% chance of failure shows up.

Don't be pompous either because we ALL do it. Every carpenter on every job has to make some sacrifice in quality (unless you're working for a billionaire on a carte blanc job). No house that I know of is truly PERFECT. No corners are perfectly square after the drywall mud is laid. No floors are perfectly level after wood shrinks and foundations shift ever so slightly. No house retains 100% of their heat or has a truly positive impact on the environment. Construction is a jungle of imperfections and ethical decisions; we just have to decide on what level of imperfection we can live with.

DC <--- who was taught carpentry under the moral standard of "Perfect is Close Enough".

Larry, you say, "This is an ethical question----can we learn new ways to do our work that will allow us to hang a door faster----without reducing quality and costing our customers less money?"

But I don't think that is a real ethical question... it's a no brainer to say that it is perfectly ethical to give someone the same quality for less money.

To be a real ethical question we would need to consider whether it is ethical to charge the same for the same quality even if we can do it faster and cheaper - are we allowed to 'cash in' on our own efficiency and ingenuity?

Or you could ask if it is unethical to go on uncaring about advances in technology that may allow us to be more efficient?

On top of that, we should be considering the effect that speed and 'efficiency' put on safety. While I have never been cut on a saw blade nor skewered by a pneumatic nail, most production framers I know have had those injuries. Is it ethical to work so fast that safety is diminished?

But as you mentioned "There are many other ethical questions...". So true.

DC

Larry , is there any possibility we could get plans for such a bench?

This is outside the carpentry ethics discussion, but I couldn't help but run some numbers.

Here's a look at the math for hanging 60 doors a day assuming an 8 hour day:

8hrs x 60min= 480min

480min/ 60 doors= 8 minutes per door!?

Even a 10 hour day leaves only 10 minutes per door! Wow. Factored into that has to be set up time, moving from house to house and just man-handling all those doors. Its a statement for efficiency if nothing else.

Matt

This goes with what Dreamcatcher was saying.

So, a client had a sewer back up in their home. The three plumbers they called all came over on time. Two were young and seemed not know how to resolve the problem, other then suggesting to call a sewer company which will charge $500.00. The clients were getting a little nervous. The third plumber came, an older gentleman, grey hair, glasses. The client showed him the sewer line, he looked, scratched his head,hummed a little, didn't say much. After 10 minutes of the plumbers inaction, the client was ready to say "thank you" and show him the door. But then, the plumber reached for his hammer, tapped on the sewer line three times, and the clog broke free. The plumber turned to the clients and said $350.00 please.

the client said," but all you did was tap on the pipe three times, I could of done that." The plumber said, $100. was to show up, $250.00 is for knowing where to tap.

I believe that, as long as the market can bear, if we have something to offer that is in demand, then we should charge for it. And when we start charging to much, then the market will find an alternative to what we are offering. Ethics do play a role in the market, and since I work in the northern suburbs of New York City it is a close knit community, and word gets out like lightning. So, if your work ethics are in the trash, you will not be working for long.

One last thought, I am finding that today clients are by far, more "educated" in the construction field then 20 or even 10 years ago. Between the internet, home shows on every other tv channel, and 1000 how to books on the rack. Come on, give me a break, I once had a client hand me 75 pages downloaded from the website for the siding we were going to install. She said, "make sure you read this before you start, thank you". And then she walked away.

Lets try to keep the dialogue going without insults.

After reading what AmazingGrace just mentioned and re-reading the posts I came to the conclusion that what we are talking about isn't solely based on the ethics of the builders out there but is also reliant on the ethics of the clients.

As I told Larry, it's unquestionably ethical to give a client a better product for less money. But that isn't often the case; more often the client demands a better product for less money. Is that ethical?

Sometimes materials prices fluctuate wildly and the builder gets stuck with the cost difference (for better or worse) is that ethical?

Often, good and ethical carpenters are disrespected by public opinion because of the poor ethical decisions of a few. Is that ethical?

These days the cost of an automobile (a sure to depreciate product) is 1/4 or more of the cost of a new home (which has some promise to appreciate) yet homes are considered over valued while the cost of cars are stomach-able by the general populous. Is that ethical?

If you read my first statement, I make a little quip at the end alluding that I might have all the answers if I were a Master Carpenter - something currently unachievable in America. I say that because it is what appears to be missing in the public's perception; that is 'professionalism'.

Most still believe that carpentry is a 'fall back' career for those who just couldn't cut it in college. Yet doctors, lawyers, accountants, and even plumbers (like AmazingGrace mentioned) retain a professional level of respect among popular opinion, even though statistics show that they are just as 'shady' as anyone else (sometimes more?).

And, similar to AmazingGrace's story of the plumber, I can go to a doctor 10 times for the same ailment - never necessarily being cured, sometimes having even worse side effects, but for sure being charged a premium every time.

How's that for 'ethical'?

DC

(sorry to write so much but it's a subject I am passionate about)

Dreamcatcher and Whodog94,

As I mentioned somewhere, the questions I asked in the recent blog about carpenters upgrading skills and tools is the tip of the ethical iceberg. Ethical questions are everywhere. Each one of us has to take our own look-see.

I apprecdiated your comments Dreamcatcher. I am glad you are passionate about what you wrote. Passion helps us write and ask the right questions.

Whodog94---If you can find FHB issue # 53, April May---I wrote an article in that issue about Production line jamb setting and door hanging. There is a photo of Al Schaeffer at his door bench. There is also a paragraph where I write about his bench. Maybe that will be helpful to you.

Thanks to all for helping clarify this ethics issue. Larry Haun

Thanks! I greatly appreciate it.

I don't see the problem that others have with Larry's methods. My take is that you can provide great work within reasonable tolerances and still produce a superior product that meets or exceeds minimum requirments and that in no way compromises ones ethics.

As a young carpenter in the early eighties, I did as I was taught initially but a new set of eyes can at times see a better way. There was always a new guy with new ideas and the resistance of the older guys to these new methods. Change is slow unless you can demonstraight practicality. When I was asked by a friend of mine to come down to Austin,Tx in the mid-late eighties, I was sufficiantly full of myself and my skills. Boy, did I ever learn. Building here in the Chicago area at the time there wasn't a hard push to beat timelines. It took what it took and what the bids timeline required, usually more but defintly not less. The mentality/methods where very differant in Austin. They had implimented many of the production methods that Larry has come to be known for. I'll be the first to say it's not for every guy as I learned. I managed to hold my own but these guys where machines---Every motion was a lesson in efficancy. The point is that I thought at the time that these "new methods" were sloppy. Over the course of that summer I came to realize that I'm was not building pianos and other fine furniature and that a eight or 1/4" off in most framing is not the end of the world. For example,how is 3/16" out of plumb in a 9 or 10 foot wall height change anything---it doesn't. If you work within acceptable tolerances and methods, you produce a fine structure that makes money and gives you satisfaction in a job well done.

I almost hate to comment since I'm not, nor ever have been, a professional in your field- just an avid reader (and dreamer) with 50 yrs. experience of manufacturing and organizational processes. The issue you describe is ancient; it has existed as long as there have been craftsmen. A skilled, conscientious craftsman uses judgement all the time- judgement as to what shortcuts matter, and which do not. That's not only acceptable; as you say, it's desirable. The problem is that it creates an atmosphere, a culture, in a working group that indiscriminately empowers the exercize of judgement- and as you know, not everybody is skilled or conscientious. The development of that "judgement" culture is a good thing in itself because it fosters creativity and joy in the work which inevitably leads to the best results. However, the issue has always been-- how do you guarantee that the judgement of OTHERS will be sound? The (ancient) problem, in all group work, has been finding the constantly changing balance of fostering creativity while simultaneously achieving discipline in its execution. That is itself a craft, and like all crafts cannot be boiled down to a few, immutable rules-- other than always watching, always listening, always caring, always accepting personal responsibility for the work of others.

Well Feeg,

As a 50 yr production/manufacturing manager you have the right thought proccesses and IMO enough gravitas to certainly comment on the topic. After all, what is building a stucture but a well choreographed manufacturing endeavor. IMO, you stated the issue very well so no need to apologize.

Now,that "Judgement factor" in the building trades is honed over time, and that indiscriminate empowerment as you put it is exercized because reality is stranger than fiction requiring you to fly by the seat of your pants at times. Yes not everybody is skilled or conscientious as to what shortcuts matter but that can always be mitigated by ones company culture---It sets the tone and ethics the tradesmen follow.

Lendgary HACK

"So the question is: What is our responsibility as carpenters, to ourselves and the people we build for, to upgrade our knowledge, methods, and tools to build quality homes at prices people can afford?"

I'm not a builder, but these questions are applicable for nearly any trade, or industry for that matter. I don't see them as ethical questions but as good business questions. If one doesn't keep up with industry standards, the consequences will be less work and less income over time. Consumers are more educated than ever before and are more capable of discerning the components of quality.

In terms of ethics, why not just apply the golden rule? Are your methods and standards the same you would apply when building for yourself? Or, are you applying the same standards you would expect of someone else building for you? Most people know in their gut when they're not behaving ethically.

On a personal note: But staying with the ethical issue. I was handed a set of plans to build a 10X16 one car garage. Plans were drawn by an architect, approved by the town, permit issued and contract signed. So, I constructed the garage as per plan and contract. Turns out that the clients car doesn't fit. Who's to blame, and who should have "within reason" done what.

Larry, thanks for posing such an interesting topic for discussion! It's good to read how others deal with this issue.

As a self-employed contractor I primarily work alone, either in the shop or on a remodeling jobsite. In either case, I must make "ethics" and quality control issues many times in any given day. Over the years (30+ in the trades) one of the best guiding principles I've learned is:

"If it takes a little work to make something a lot better, its worth it. If it takes a whole lot of work to make something just a little bit better, it's probably not worth it."

It's usually quite easy to make a decision after running it through this test.

Matt

amazingrace,

I certainly do not blame you, you where building what was called for on approved plans. The Contractor and Architect have much more reponsibility because they had the primary interaction with the client and should have screened the client's actual needs.

Just out of curousity, how long did it take to complete the garage? The reason I ask is I've witnessed the local garage outfits build a completed 2car in one day less power. The electrician shows up within a few days. If it's me any my crew, its a 2 to 2-1/2 day turn.

Hey 316, the plans call out for a block foundation 42" below grade. So, between excavation, footings, block, backfill, and slab. That was 8 days. I framed with roof, siding and windows in another 3 days. So, by the third week everyone was happy until the owner pulls his car in. You know, if it wasn't for the fact that it was my job, it was almost laughable. But it wasn't. The architect doesn't have anything to say, the owner is pissed, and I'm left with a 3K outstanding balance.