An Oregon-based company has contacted more than 300 homebuilders in Oregon and Washington demanding a $150-per-house licensing fee for using fans and dehumidifiers to dry out houses under construction.

The National Association of Home Builders, a national trade group, says they are victims of a “patent troll,” in which a patent owner claims infringement in order to extract licensing fees but doesn’t use the patent directly in his or her own business. The drying process covered by the patent has been in common use for more than three decades, according to a laywer working on behalf of builders in the region, and no one can understand how Robert and Andrew Weisenberger won the patent in the first place.

“The patent is of very dubious quality and was rejected, in fact, three times before it was finally granted,” says Alex Strong, a member of the government-affairs staff of NAHB. Government records show the Weisenbergers filed for the patent in July 2003 and that it was granted more than a decade later.

But the Weisenbergers, father-and-son majority shareholders of a company called Savannah IP, claim they originated the idea of drying out wood framing during construction to reduce the risk of mold in wall cavities. “Builders have been using our process for 10 years now and they just think they have been using it for decades,” Andrew Weisenberger said in a written statement.

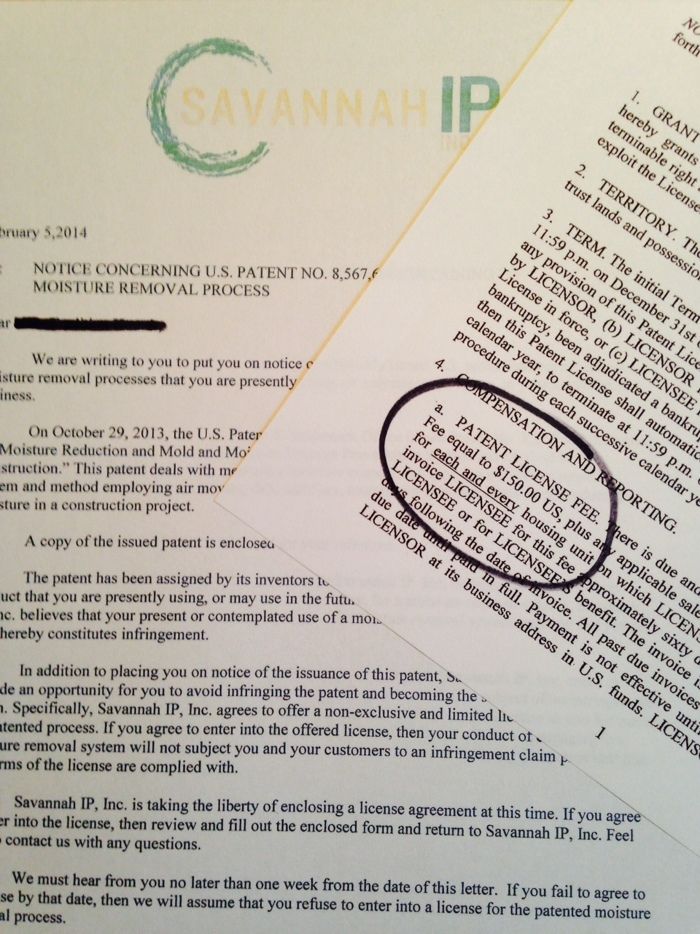

The dispute revolves around U.S. Patent 8,567,688, granted to the Weisenbergers in October 2013 and since assigned to Savannah. It vaguely describes a process of removing excess moisture from houses under construction to prevent the growth of mold in wall cavities. The description on file with the U.S. Patent Office describes it this way: “A moisture-removal system employing air movers, dehumidifiers, heaters, and attendant methods for reducing moisture in a construction project.”

Savannah IP cites the patent in the hundreds of letters it has sent to builders, warning they could face legal action unless they paid $150 per home and agreed to a long list of other terms, including penalties of up to $5000 for under-reporting the number of houses they build.

“What’s troll-like about this company,” Strong said, “is they are blanketing our members in the Pacific Northwest with these letters and we have every expectation they will expand this with any success to a nationwide effort. The short of it is that builders are being targeted by virute of the fact they are building homes, not necessarily that this company knows they are violating or infringing upon their patent.”

“We thought it might be a hoax”

Fish Construction NW of Portland, Ore., was one of the builders that got the demand letter, says Justin Wood, one of the firm’s owners.

Fish Construction doesn’t dry out the frames of houses itself, as is now required by code, but hires a third-party to do the work. At first, Wood said, they thought the letter might be a hoax because it involved a “fairly generic process” used in the region.

The company contacted its attorney, who wrote back to Savannah seeking more details. The company never responded.

Fish said there’s ample evidence the process claimed by the Weisenbergers has been in practice for some time. There’s nothing “novel or unique” about it to him.

Wood and others who received demand letters had good reason to raise their eyebrows. It wasn’t just the $150-per-house licensing fee, but a long list of other conditions that Savannah sought, including:

- With 30-days written notice, Savannah is permitted to modify the patent fee.

- The builder is required to file quarterly written statements “certifying the addresses” of new-home building permits.

- Savannah has the right, with 30-days written notice, to inspect the builder’s books to make sure the reports are accurate, and the builder has to keep the records available for three years.

- If the builder omits a house, he’s liable for an “enhanced patent-license fee” of $1000 for the first instance and $5000 for additional omissions.

- The builder can’t talk about the license agreement with anyone. Provisions of the license agreement, including the fees and the builder’s payments, “are confidential and trade secrets.”

- The builder is required to notify his or her customers that the moisture-removal process used on the house is covered by the patent owned by Savannah.

- Barring certain conditions, the agreement automatically renews itself each year.

Patent owners respond

In a written response to questions submitted by Fine Homebuilding, Andrew Weisenbergers said he and his father ran a company called Home Certified Inc. from 2003 to 2009 where they developed the idea. “We have personally frame dried mid-construction over a thousand new homes,” he said.

The statement also said they have been doing “fire/water restoration” since 1993. “As part of that, we are general contractors and handle all phases of rebuilding a damaged structure,” he said, “including building an entire new structure if needed.”

The Weisenbergers said they sent letters to a total of 326 builders that had pulled permits in Oregon and Washington. None has signed an agreement to date, although the new owners of Home Certified agreed to pay a licensing fee for using the process when they bought the business.

“When we started selling our process to builders 10 years ago there was not one builder we could find that had ever heard of mid-construction frame drying to bring the moisture content of the frame to below 19%,” Andrew Weisenberger wrote, “And we talked to every builder that we could find. Large or small, it was a difficult sell to get them to use our service.”

Despite an initial hesitation, the statement continued, “we convinced them, literally one at a time.”

“So what happened?” Andrew Weisenberger said. “The wall-cavity mold issues did go away when our process was used. And the related lawsuits went away as did the extremely bad PR for the buider.”

An Oregon task force in 2007 recommended that building codes require wood framing not exceed 19% moisture content. No other state in the country was addressing the problem, the statement said.

“We feel comfortable with the statement that our process was not in use prior to us using it and that, in fact, we invented the process,” their statement said. “The [Patent and Trademark Office] agrees.”

And as to patent trolling, the statement says the term is “undefined, is a charged term, and is used by people to advance their own agenda.”

“It’s clear that people come up with new ideas every day that get patented and then they license companies to manufacture and sell the product or use the process,” the statement said. “Doing that should not make them a patent troll.”

Nipping the problem in the bud

Jamie Howsley, an attorney with Jordan Ramis in Vancouver, Wash., concedes the patent is valid but says it describes a process that builders have been using for decades–not something the Weisenbergers invented 10 years ago.

“What is sort of frustrating to folks who have been in the building industry is this has been a long-known process that people have used for 33 years or more, and it’s actually reflected in a lot of the building codes in Washington and Oregon,” he said. “The first reaction from a lot of these builders was how in the heck did this outfit receive a patent on this process, for something that is pretty commonplace.”

Howsley, whose work typically involves land use and real estate, also has helped a local building association in southwest Washington where builders began complaining in January they were getting demand letters.

Builders in the region are used to getting similar demands, he said, but this appears to be the first time it involved a valid patent.

Challenging the patent could be quite expensive, he said. “So it seems to me it’s a way to get a quick buck and try to move on, to try and trap the unwary. Clearly, it’s vague enough that they’re trying to get people into a trap just so they pay the fee and go away, and that’s why there’s a low dollar amount asked and they’re not coming up with specifics on how and when you may have violated this, ‘we just think you’re doing this.'”

Both Howsley and Strong are concerned Savannah’s efforts will spread beyond the Pacific Northwest, and affect commercial as well as residential builders.

Earlier this month, NAHB announced its support for a bill now pending in Congress designed to stop patent abuse. Strong said one measure in the Senate (S. 1720) would make sending intentionally vague demand letters a deceptive or unfair trade practice under federal law.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Affordable IR Camera

Reliable Crimp Connectors

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Pay Up: Builders in Oregon and Washington have been getting letters like this from a company called Savannah IP. The letter demands a $150-per-house licensing fee for a moisture removal process that builders in the region reportedly have been using for decades.