Is Solar Power the Solution?

Solar panels might be a wise investment in light of a generous federal tax credit set to expire by the end of 2019.

Topher Donahue/Aurora Photos/Corbis

Topher Donahue/Aurora Photos/Corbis

Tracking the prices of energy and gasoline is a staple of news reports, but those same reports largely have ignored the steep decline in the cost of photovoltaic (PV) systems—from over $10 per watt in 2000 to around $3.48 per watt in the first quarter of 2015. At this price, solar installers say that there’s never been a better time to go solar, and steadily rising electric rates suggest they’re right—in principle. However, most Americans are daunted by the perceived substantial cost of a PV system—perceived because the average homeowner finds the incentive-riddled pricing structure of PV systems to be murky, is unaware that prices have fallen dramatically, and is often not sure if electric rates are high enough to offset an investment in solar.

Many homeowners still believe that solar is for the wealthy. SolarCity CEO Lyndon Rive has acknowledged in interviews that his company wants to remove the stigma of high costs from solar power. For those who can’t afford the up-front cost of purchasing a PV system—and at $13,000 for an average 5kw array after incentives (give or take a few grand), that’s a lot of people—solar companies offer financing and leasing plans to replicate the traditional monthly electric payment. They have made going solar more attractive by reducing homeowners’ monthly payments and offering price stability over 20 to 30 years.

Solar panels reduce the amount of grid-supplied electricity you must purchase and can be considered an energy-conservation strategy. Unlike with weatherization improvements or switching heating fuels, both the cost of the work and the amount of financial savings with solar are calculated accurately beforehand. If you’re looking to save money, it’s a straight-off-your-bill deduction independent of other efficiency improvements. To figure out the payoff of adding solar to your rooftop, you need to weigh your electrical usage against the solar potential of your property and compare your utility rate to the installed cost of a solar array.

Supply and demand in an economy of one

To get a grasp on your personal solar economics, you first need to calculate your demand. Gather the last year (two years if you can) of electrical bills, and tally your monthly usage to arrive at your annual consumption. This is your demand expressed in kilowatt hours (kwh). Last year, for example, my family used 5700kwh. We live in Connecticut and have fairly high utility rates: Our generation charges are 20¢ per kwh, and with transmission and distribution charges, we paid $1200 to power our house for the year.

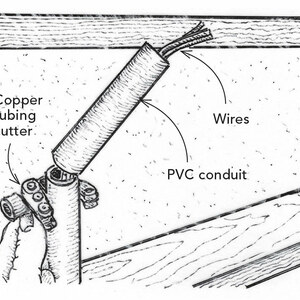

Supply is the amount of electricity you can produce, in most cases from a rooftop system but alternatively from a ground-mounted array. You can estimate this using the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s PVWatts calculator (pvwatts.nrel.gov). Using satellite mapping photos, the calculator allows you to mark the area of your roof available for panels and to adjust default variables such as roof slope. The calculator combines this information with geographic, climate, and economic data, and then it spits back the size of the system that will fit on the roof and the amount of energy it will generate during the year. For my roof, it was a 5kw system that would generate 6176kwh per year of electricity—more than enough to offset my annual usage of 5700kwh. Solar companies also perform this calculation, but with an on-site visit to account for shading.

Now that you know demand and supply, the price of the solar array will determine whether it makes sense to purchase one. In July 2015, Sungevity quoted a price of $18,709 for a 5kw system in Connecticut. However, the quoted cost is not the full story. Although state and local incentives generally are winding down, there are still plenty of rebates in force. (You can find state, municipal, and utility incentive programs in the dsireusa.org database. Solar companies in your area also know the current incentives.) Here in Connecticut, the state’s clean-energy program has an incentive for rooftop systems up to 10kw. Over time, this incentive has been reduced, but in July it was 54¢ per watt, or $2700, for a 5kw array.

After the state incentive (paid to the solar company and deducted from the price), the out-of-pocket cost in my example would be $16,009, which lowers the installed cost to $3.20 per watt from $3.74 per watt. Come tax time, I’d be eligible for a 30% credit on my federal taxes, reducing the final cost to $11,206. Because it’s a tax credit, it only applies to my tax liability for the year. If my taxes were less than the credit—in this case, $4800 in 2015—the remaining portion of the credit would roll over to 2016.

PV Parity

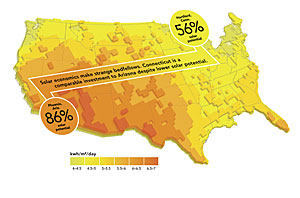

In theory, solar arrays have the biggest payoff in regions where electric rates are high and sunshine is plentiful. The map shows the solar potential of different areas of the country. Phoenix clearly has much more solar potential (86%) because of the amount of sunlight it receives, yet the high utility costs and favorable policies (rebates and net metering) in Hartford, Conn., which has cloud-free sun only 56% of the year, make it economically viable to put solar on your roof there as well. In fact, solar is a better investment in Boston than in any Arizona city.

Buying solar panels is an investment

Financially, there are three ways to get a PV system on your roof: You can buy it outright, finance it, or lease it. Buying the system—whether you pay cash up front or finance the purchase—has the distinct advantage of giving you ownership of the array and the incentives that come with ownership.

Often potential solar customers look at simple payback. Divide the cost of the PV system by the average monthly electric bill savings, and you’ve got the number of months until the savings have paid for the system. In my case, this would be during the ninth year, which would make the next 15-plus years of electricity free. An alternative is to divide the total cost of the system—$11,206 in my case, plus $3000 to replace the inverter at some future time—by the total anticipated electrical output over an estimated 25-year life span of the array: 154,400kwh. That works out to roughly 9¢ per kwh (which may be slightly higher depending on how much the panels degrade over time). This simple cost calculation is significantly less than my utility rate, which will increase regularly. Paying for a PV system up front will put a dent in your savings, but it will improve your monthly cash flow—noticeably if you have high electric bills. But financing a PV system may be a better option if you look at going solar as an investment.

The success of many large, national solar companies allows them to offer low-interest, long-term financing for solar arrays. For instance, a $16,000 loan at SolarCity’s July 2015 terms (4.5% for 30 years) means that the monthly cost of a fully financed 5kw system is about $81 (plus you get to take the federal tax credit). If your electric rates are high enough to generate significant savings with PV and incentives remain, fully financing an array can gain you a better return even if you have the cash to buy it outright.

Going Solar in America, a recent report by the N.C. Clean Energy Technology Center, compares the net present value (NPV) of purchasing an array to the NPV of financing an array. NPV shows the future (25 years) value of the solar array in present-day dollars. Among the data Going Solar in America reports is that the NPV of a 5kw array purchased with cash is $6275 in Boston and $14,987 in San Francisco. Fully financing the same array changes the NPV to $11,830 in Boston and $21,859 in San Francisco. Overall, the report finds that the up-front purchase of a 5kw solar array in 20 of the 50 largest cities in the United States is a better investment than the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index (assuming a 6.61% annual return). But fully financing the array makes it a better investment in 42 of those cities. In regions with low electric rates and/or solar-unfriendly regulatory policies, it’s tough to make a return at all on the investment. In Jacksonville, Fla., for example, the NPV of a fully financed array is $2104, but if it’s paid for up front, the NPV is –$3871.

As with any investment, it’s important to know how liquid it is. If you decide to move, will your home’s sale price reflect a premium for the solar array? The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory recently compared the sales of almost 4000 homes with solar panels between 2002 and 2013 to a pool of nearly 19,000 non-PV homes picked to match the features of the PV homes (house size, lot size, number of bedrooms, etc.). It found that a solar array adds an average of about $4 per watt to the sale price of a house and that the PV premium over time tended to decline, accounting for falling equipment prices and rebates. (One caveat: The sample for the study didn’t allow researchers to look at resale pricing on PV systems more than 10 years old, but it appears that homebuyers depreciate the value of panels quickly.)

PV payments: buy vs. Finance vs. Lease

The cost of a solar array varies around the country and is affected by hardware costs, demand, and the cost of grid electricity. In many markets, competition is intense, so it’s worth getting several estimates to find the best price. The chart shows the average cost of a 5kw array in three states according to SEIA and GMT Research’s Solar Market Insight report for the second quarter of 2015.

| LOCATION

of 5kw Array

|

BUY

Before incentives |

FINANCE

0% down, 4.5% APR for 30 years |

30-YR. LEASE

First year (3% annual increase) |

| California | $21,550 | $109 per mo. | $168 per mo. |

| Texas | $17,900 | $91 per mo. | $115 per mo. |

| Massachusetts | $24,700 | $125 per mo. | $130 per mo. |

Lease plans have broadened the market

Solar companies have used lease and power-purchase agreements (PPA) to broaden their market appeal. Households are used to paying a monthly utility bill; if a solar company can take a cut of that monthly payment and lower the monthly bill for the homeowner, they both win. With a lease, the homeowner pays rent on the equipment and gets the solar production as part of the bargain. The monthly payments are defined for the life of the lease. With a PPA, the equipment is installed free of charge, and the homeowner pays for all the electricity the array produces. The monthly payments are per kwh of electricity, typically at or slightly below the retail cost of grid electricity. For both leases and PPAs, there typically is an escalation clause of between 2% and 3% annually. (Nationally, the average utility-rate increase since 2002 is about 4% a year.)

There are some conventions of the leasing and PPA process to know about before meeting with a solar company’s representative. If you choose a lease or a PPA, the company installing the panels owns them and cashes in the credits and/or rebates. Another critical thing to know is that leases and PPAs are 20-year contracts. That means if you decide to sell your house, you may be limiting the pool of potential buyers. If the potential buyer doesn’t want to (or isn’t approved to) assume the lease, you are responsible for paying the remaining amount due.

Households are used to paying a monthly utility bill; if a solar company can take a cut of that monthly payment and lower the monthly bill for the homeowner, they both win.

Turning the grid into a storage device

Most homes with solar panels are not defecting from the grid. When the PV system produces more electricity than the house is using, the surplus is diverted to the local grid and is consumed by neighbors. When PV production is less than the household’s demand, it draws electricity from the grid. The meter keeps track of inflows and outflows, “netting” the monthly usage.

Net metering is an accounting method that lets homeowners effectively time-shift their production and consumption of energy, a critical feature in the economics of residential solar power. The amount of solar energy generated throughout a day varies with the sun’s path. Production also varies with the season, diminishing during the winter from shorter, cloudier days and a lower sun path. With consumption waxing and waning throughout the day and the year, peak-use times don’t necessarily match up to peak-generation times. Net metering can be understood as a way to turn the grid into a giant storage device that allows homeowners with PV systems to bank excess electricity from high-production periods and then consume it when their demand exceeds their panels’ production.

Net metering is required by law in 43 states and the District of Columbia, but the conditions vary. The most advantageous net-metering rules allow homeowners to carry over surpluses from month to month. In these situations, if the array produces more electricity than the home consumes during a month, the utility company issues a credit for the excess production that is rolled over to count against consumption in the upcoming months. In most cases, the homeowner must use up this credit during the solar year, which often runs from July 1 to June 30. If there’s a surplus at the end of the year, the credit may expire or the utility may cash out the excess production at a specified tariff. Valuing that excess production has become a matter of dispute.

In most locations, the price a utility assigns to solar electricity is very low because the utility pays the wholesale rate for electricity, also known as the avoided cost, rather than the retail rate that homeowners think of as the price of power. Because reimbursement is so low, it doesn’t make sense to invest in an oversize system that will generate a surplus of electricity over the year. That’s one reason why checking your historical use when you size the system is important. Another reason is that local incentives may be based on historical usage. Even if that’s the case, it’s worth considering any future changes to your electricity consumption before sizing the array. If you plan on building an addition, installing a pool, adding central air-conditioning, switching from natural gas or oil to electric, or purchasing a plug-in vehicle, be sure to account for that. Conversely, energy-efficiency improvements can decrease the size of a planned array—although not necessarily at a cost-effective price. It’s worth noting that you can’t reduce your bill to zero; utilities charge connection/transmission/distribution fees regard less of electrical usage. My utility, for example, charges $19 per month ($228 per year).

Can solar survive without incentives?

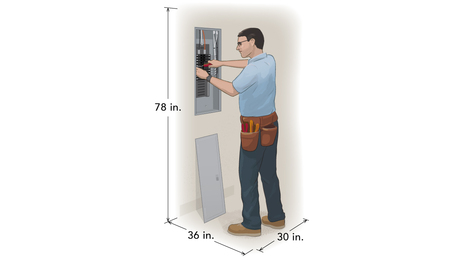

The federal 30% tax credit for solar installations is due to expire at the end of 2016. Even if Congress doesn’t agree on extending the tax credit (a strong possibility in the current political climate), states’ policies could drive down the costs related to permits and inspections from multiple government departments and the utility company. According to a Department of Energy report, these “soft costs” add up to $2500 to the cost of a 5kw system. Removing this red tape—as Vermont has done with a one-page online application for all permits, will help drive down the cost of PV. (See how your state’s connection policies rate at freethegrid.com.)

Will solar adoption continue to grow if Congress doesn’t renew the credit? Yes, but smaller solar companies may be driven out of business. Solar incentives were introduced to help launch a fledgling industry; as the price of solar hardware has fallen, local incentives have been reduced. Whether in place or expired, these incentives have been remark ably successful. In California and Arizona, state and utility incentives have dried up, yet the rate of solar adoption has accelerated. A recent study by Greentech Media and the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) found that in the first quarter of 2015, nearly 25% of all residential solar installations came online without any state- or utility-level incentive, up from 2% in 2012. If you’re planning on taking advantage of the 30% federal tax credit, keep in mind that the system must be installed before December 31, 2016, and that, depending on the market, it can take from several weeks to several months from when the contract is signed until the system is energized. An unused solar credit cannot be carried over to 2017 if Congress doesn’t renew the credit.

PV Power to the People

How much does a kilowatt hour of electricity cost? It depends on whom you ask. The fee that utilities pay to suppliers is one amount. Tack on transmission, connection, and distribution charges, and you’ve got the price consumers pay. What price do you assign to solar energy that homeowners put back onto the grid?

Utilities say solar costs them money

While the net-metering process isn’t perfect, it’s an effective way to time-shift production by allowing homeowners to “store” electricity on the grid. While there are critics of net metering among both PV supporters and utility companies, the troubling complaint for a prospective solar owner is from the utilities. Some utilities argue that PV customers are essentially free-riders, hopping on and off the grid when it suits them and shifting infrastructure and maintenance costs to nonsolar customers. In at least 20 states, utilities have requested to be allowed to levy additional charges specifically on customers with PV systems. So far, these requests have been rejected. The utilities are responding to a changing business model and declining revenues; as renewable-energy adoption increases, PV owners are not purchasing as much energy from the grid as the utilities predicted. Given the still very low national rate of PV adoption (less than 1% of households), however, the increase in household solar production doesn’t account for falling revenue. In fact, data from the U.S. Energy Information Agency shows that electrical consumption has been falling steadily for years because of customers’ energy-efficiency improvements.

Solar owners say they’re underpaid for surplus

on the other side of the argument, PV owners and many policy advocates argue that net metering doesn’t go nearly far enough in recognizing the value of PV to the grid. In places that pay for surplus production, the homeowners are likely to receive the avoided cost, or wholesale rate, for their electricity. Some solar advocates would rather see an accounting method that factors in all the avoided externalities of solar: avoided fuel costs for the utility, avoided greenhouse-gas emissions, avoided transmission costs, reduced need to use and build standby generation, reduced transmission losses, and avoided internalized emission costs. Several studies have created models for calculating the benefits of solar to the community of utility-rate payers. one study found a $92 million annual benefit to California; a similar study set the figure at $520 million annually in Texas.

A new paradigm?

Austin, Texas, and the state of Minnesota have each created an alternative to net metering that uses what’s called a value-of-solar approach. In Austin each year, a consulting firm calculates a value for electricity generated by residential solar arrays by creating a price for the avoided externalities. Customers are billed for all of the electricity they consumed from Austin Energy during the billing period, and they receive a credit for all the electricity they generated. In 2015, the solar energy is credited at 11.3¢ per kwh. Excess credits are rolled over each month and don’t expire. Minnesota adopted a statewide policy in 2014 requiring investor-owned utilities to offer a value-of-solar pricing tariff. The interesting difference between the Minnesota plan and the Austin plan is that in Minnesota, homeowners (the energy producers) sign a 25-year contract (the expected life of a PV system) with the utility guaranteeing the price for energy produced. The goal is to have utilities pay homeowners a transparent and market-based price for solar energy.

These two value-of-solar schemes are important to PV owners because they incorporate a price for pollution. Also, because the price is more than the wholesale cost of electricity, it undercuts utilities’ claims that solar power fed to the grid is worth less.

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

Why not let solar make it on merit rather than Federal subsidies...???

http://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/centrally-planned-energy-bad-economy-bad-environment

http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/ivanpah-time-end-subsidies

I'd be in favor of ending subsidies on renewable energy technology as long as direct and indirect subsidies for fossil fuels were eliminated as well. Solar (and other renewables) would be far cheaper. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ucenergy/2017/02/01/the-200-billion-fossil-fuel-subsidy-youve-never-heard-of/#335eaf9c652b