A Workaround Approach to Kneewall Built-Ins

Without modifying the framing, a carpenter tucks storage and style beneath the roof in a second-floor hallway.

This Cape Cod-style bungalow was built just before World War II (the war that would change everything, including the way houses are built). It’s compact and efficient, with a steep roof made of intersecting gables and eaves with no overhangs. It has simple moldings and few extras. The house reflects its era—a time of great struggle—with a modest amount of comfort.

Though the current homeowners appreciate their home’s history, they’re a growing modern family and needed more storage. But adding built-ins that protrude into any of the home’s small rooms would mean losing valuable floor space, which is at a premium in this house. So when I was hired for the project, I suggested we turn our attention to the narrow second-floor hallway at the top of the home’s steep winder stairs. It’s a spacious, light-filled area, and the 4-ft.-high kneewall under the sloped ceiling left us with an unclaimed triangle of attic space to work with—or, perhaps more accurately, to work around.

Designed to fit in

Like most roofs of its day, these 2×4 rafters were framed 24 in. on center, and the kneewall was framed to match with a stud aligned with each rafter. Though they are undersize according to modern building codes, these simple roof assemblies seem to stand the test of time in our climate and under our limited snow load. All the elements of the assembly are critical to its success—the rafters, collar ties, kneewall, exterior wall, and floor joists create strength through geometry. This means old roof frames such as this one are a lot like roofs framed with modern engineered trusses: You can’t modify them in any way without creating a major weakness.

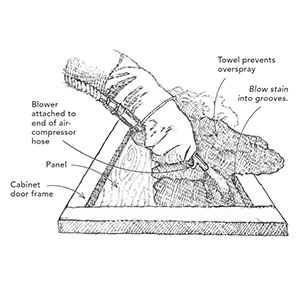

Not wanting to open a can of engineering worms, we decided to work around the existing framing to reclaim the attic space, setting a row of built-ins into the spaces between the studs. To avoid mistakes, we determined that it would be best to build the cabinet carcases in the shop, and then assemble the face frames on site after the carcases had been installed. The homeowners asked for a seamless look, and we felt that doing the face frames on site would offer flexibility in the process and allow us to fine-tune how everything would fit, making the new built-ins look like part of the original design.

The final plan uses five stud bays at the face of the kneewall—each approximately 22-1⁄2 in. wide and 44 in. tall—for a run of bookcases. Each open-shelf bookcase is anchored with a deep bottom drawer, and the assembly is complemented by a linen closet set in the corner at the top of the stairs, which does not enter into the attic space. We replaced an existing linen cabinet with this larger unit, pulling the piece farther forward to create additional storage and make better use of the jogged hallway.

Because the stud spacing varied slightly, we chose to build the bookcases to the smallest dimension. This simpified the process so the caracases would fit in all the bays with enough space to shim them level and plumb. Making the most of the triangular space, the open bookshelves are only 11-1⁄4 in. deep, but the bottom drawers extend back 24-1⁄2 in.

The built-ins are intended to look simple and clean. Because we were working around the kneewall studs, we knew that the stiles between the units would be wider than usual, as would the top rail, which has to accommodate the kneewall top plate. We opted for overlay drawer fronts to help de-emphasize the chunky face frame.

An extra-careful install

We’re used to working in older homes that present unique challenges, and this project was no different. The surrounding walls, floor, and ceiling were all out-of-level and out-of-plumb, ranging from mild to wild. The corner linen cabinet was straightforward to install and the first thing we tackled. Once that was in place, we began prepping the attic space to receive the built-in carcasses. After removing the drywall, the first step was to fasten a 2×4 (on the flat) over the floor joists for the back of the carcases to rest on. The 2×4 brought the cabinets level with the hardwood floors on the finished side of the kneewall (3⁄4-in. subfloor + 3⁄4-in. hardwood floors = 1-1⁄2 in.). Once we determined the height we wanted the cabinets to sit above the finished floor, we used blocking to lift and shims to level the individual units.

The key to a successful installation on this project was keeping all the carcases square and in plane with each other so that we could install the face frames as a (mostly) single unit, tying all five carcases together. Taking the time at this stage to get all the carcases in the correct position made the rest of the install much easier. We weren’t concerned with getting the spacing between the units exactly uniform. As long as they were vertically parallel, the stiles would fit nicely, and we were happy to rip each stile to a custom width. Because the stiles are wider than usual to begin with, the differences in spacing aren’t noticeable.

Using a laser level to set the elevation, we started by installing the end units and worked toward the middle. This allowed us to use a straightedge to check that we were keeping all the carcase fronts in plane with each other.

Finely tuned face frame

With the carcases installed, we turned our attention to the face frame, starting with the stiles at the ends of the units and the top and bottom rails. First we fit the stiles on the left and right ends, scribing them to the walls and ceiling as needed while also setting the proper overlap over the sidewall of the carcases. A 1⁄8-in. overlap creates an inside corner between stile and carcase that can be caulked to hide any gaps that may show up once the cabinets are painted white. Once these stiles fit well, we temporarily screwed them in place to ensure they didn’t move as we measured for the top and bottom rails and marked where they should attach to the stiles.

The bottom rail was fairly simple to fit as the floor is mostly level and we planned to add a base shoe to cover any slight gaps. The top rail was another story—the sloped ceiling has a significant cant from left to right and is bowed in the middle. With both end-stiles fit from floor to ceiling, we realized that we could use the stiles themselves as reference points to rip the top rail, which we left extra wide and then cut after the face frame was assembled (drawing left). In this way, the beveled rip matches the cant of the ceiling from one end of the built-ins to the other.

Once we were happy with the fit of the perimeter frame, adding the intermediate stiles was a fairly straightforward process, as we had already done the work of ensuring that all components were square. We marked the position of the interior stiles, cut them each to the necessary width, and again removed the frame to install them using pocket screws.

Finally, we installed the assembled face frame using glue on the carcase edges and countersunk screws driven into the kneewall framing (not the carcases, because the 1⁄2-in. plywood chosen for the carcase sides would have been a risky target for finish nails). The remaining shelf rails were glued and nailed in place before we spent a couple hours plugging the screw holes, filling the pinholes, and sanding everything to create a seamless frame. It’s worth noting that this approach is best suited for a painted installation. It could be done on a stain-grade project, but you would be adding a complication when it comes time to hide all your fasteners.

We returned to complete the installation of the drawer boxes, fronts, and hardware after the painters had done their work. The final result is as functional as it is charming and adds a lot of visual interest in what would otherwise be a rather unremarkable hallway. And we did it all without disturbing the framing, which would have required an engineer, permits, additional trades, and a much larger budget.