A Revolution in Building

Houses are becoming more complicated, material options are multiplying, and our workforce is stretched thin. We can all do more to help.

Synopsis: In the last 15 years, we have seen huge changes in building technology and science. New material options, installation details, and maintenance concerns mean that builders are scrambling to keep up with changes. At the same time, a disappearing workforce means an undermanned pool of tradespeople. We can all do more to help product manufacturers, by clarifying installation details and technical documents; architects and designers, by taking the building plans further; and builders, by staying up to date with relevant information.

The last 15 years have seen more changes in building technology and science than the 50 years that came before. Maybe 100 years.

Pick any year between 1950 and 2000, and any capable carpenter could walk onto any residential job site and identify the building assemblies without missing a beat. We had a formula. Sure, there were slight variations, and some outliers, but for the most part every house was built from the same stuff: formed-concrete or stacked-block foundations, 2x lumber from mudsills to roof rafters, plywood sheathing, housewrap on the walls, felt paper on the roof, and fiberglass batts in the framing cavities. Manufacturers varied, but generally the products were interchangeable, and the playing field was level. For a lot of the builders in this country, that recipe is still the go-to, and still working fine—but for others, those days feel like the distant past.

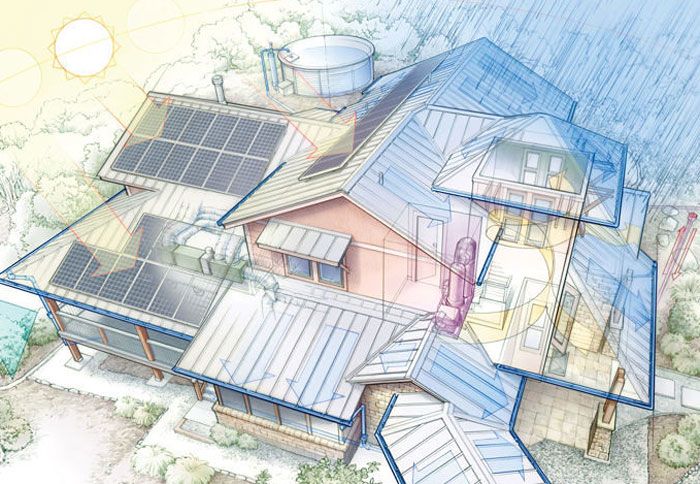

Now, you might drive by a house under construction and see an insulated-block foundation stacked on-site, or a truck craning a factory-built prefab foundation into place, or maybe even a house without a concrete slab. It’s increasingly common to see houses with ZIP System sheathing on the outside, a liquid membrane being rolled on, or sheets of adhesive-backed membrane being stuck into place. If you go inside, you’re likely to find one house has open-cell spray foam, another has closed-cell foam, and a third has 12-in.-thick walls full of dense-pack cellulose. This is great, right? We have so many more options than ever before, and the market of building materials is exploding with growth. The way we’re building nowadays is better on almost every level—but it does raise some new concerns.

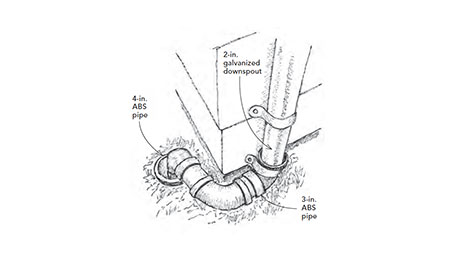

When you put yourself in the boots of those builders on the job site, you understand that their world has become infinitely more complex. Many builders are scrambling to keep up with changes in installation, material science, and maintenance concerns, and the risk of all those pieces coming together incorrectly or failing soon thereafter is exponentially higher. Seasonal expansion and contraction, UV degradation, fire, and other factors are still a concern, but most of what keeps builders up at night these days is water.

Those houses from 30 years ago with Tyvek, plywood, and fiberglass could take a beating in terms of moisture. Whether from leaks or vapor movement through the structure, they could get wet and in many cases just dry out. Products installed wrong were still a problem, of course, but they may not have revealed them- selves as problems for several decades, if ever. Nowadays, if you get an assembly wrong and you trap moisture, you risk the whole thing failing catastrophically—not decades down the line, but often in a year or two.

Sounds pretty scary, right? That’s just part of the equation. The other change happening at the same time is a disappearing workforce. We’re losing shop class in our high schools—that was our farm team. We’re losing kids to four-year colleges, because it’s not socially acceptable to be in the trades anymore. And those that still choose to follow a path toward a life in building don’t have as many opportunities for training. There are certainly less trade schools, and there are virtually no apprentice- ships anymore. Instead, many people new to the trade are learning how to build by work- ing for the guys who learned the trade 30 years ago—back when everybody built the same house—and didn’t bother changing with the times.

So what are we left with? An incredibly broad and complex array of building-material options that gets more complicated every day, and a vastly undermanned, undertrained pool of tradespeople that gets smaller every year.

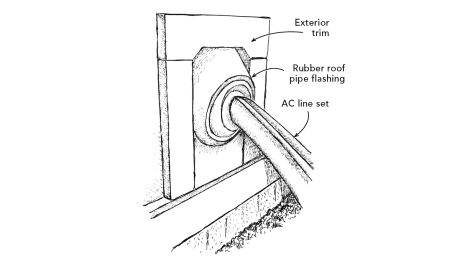

Consider this example: Most carpenters know how to install a window, but what happens if you take that window and you put it over rigid foam, or under rigid foam, or over a fully adhered membrane, or as part of a ventilated rainscreen? Things get more complicated. Who’s helping the builder figure it out?

There are some manufacturers dedicated to product-based solutions and technical support. There are some exceptional architects and designers working these things out and detailing them exhaustively on the building plans. And there are, of course, exceptional builders doing deep research into build- ing science and best practices. But in the grand scheme of American residential construction, that’s just what these people are—the exception. For the most part, builders in the field are left to figure this stuff out on their own. We can help them, and they can help them- selves, but it will take work, and it involves all of us.

Product manufacturers can do more

A growing number of manufacturers have realized that success depends not only on the quality of their product, but also on the skill of and the instructions given to the builder who’s installing it.

Although it’s not feasible in every instance, the biggest opportunity to provide crucial installation guidance is to print it right on the products themselves. If window manufacturers don’t want the bottom nailing fin taped, why not print that right on the bottom nailing fin? If polyiso rigid foam isn’t intended for use below grade because it can degrade in con- tact with moisture, why not use a small portion of the 32 sq. ft. of space on each sheet to say so? If a particular brand of housewrap requires cap fasteners for installation, why not write that on the housewrap itself? If the majority of the industry is still using faced fiberglass batts, and the manufacturer wants those batts installed so that the paper facing is on the “warm in winter” side of the assembly, why not print that on the facing? The list goes on and on.

Of course, some manufacturers already do this. For example, each piece of WindsorOne trim is still stamped with a reminder to prime all cuts, and ZIP System seam tape now includes a graphic and label every few feet to remind installers to roll the tape for proper adhesion.

For products that require more-detailed installation guidance, manufacturers can make it easier to find help. First, list a phone number to call for technical questions, because emailing a company for additional information isn’t a speedy solution. Even better, add a QR code that builders can scan with their smartphone to pull up helpful information such as technical documents and instructional videos, and make the code unique to the product in their hand; don’t just drop them onto a page with 142 different products to sort through.

When it comes to creating these technical documents, the most important thing is organizing the information well, and making it comprehensive. If a product says to install according to a specific ASTM standard, and a digital copy

of that standard costs $100, what are the chances a builder will go to those lengths? Roadblocks preventing builders from accessing information that’s critical to their success must be removed.

Many manufacturers are now using video to supplement their installation information. That’s great, because seeing a product demonstration goes

a long way for those who are visual learners.

Finally, it’s no mistake that builders tend to flock to the manufacturers who offer a “systems approach” to building. A house is made up of lots of parts—membranes, adhesives, coatings, and more— and bringing all of those parts together is a risky prospect for anybody who doesn’t hold a degree in chemical engineering. If builders can use a single brand for their flashing tape, sealant, and water- resistive barrier, for example, you better believe that they will. It gives peace of mind that those products are designed and tested to work together, and it means only one phone call is needed if something fails.

The reasoning for manufacturers to raise these standards is obvious: If you make good building materials, and educate people how to use them properly, neither will be as likely to fail. This means your brand becomes more trustworthy, and you just earned the trust of a builder who will use the products again and again.

Architects and designers can do more

Let’s agree to make 2020 the year when all designers and architects stop using the “by others” and “typ.” (typical) designators on building plans, which only pass the buck to the builder in the field, or assume knowledge of a “standard” detail when “standard” often no longer applies. Why not take the building plans a step further and include pertinent installation details, if only on a high level, rather than leave a builder in the field to decide between trying to look up the information on a smartphone or just winging it? This doesn’t just apply to special details or products; it matters with even the most standard. Window- installation instructions are anything but “typical” from one manufacturer to the next, with each requiring different details that can mean the difference between a window that leaks and one that doesn’t, not to mention retaining any chance of a warranty claim.

Some of this is as simple as architects or designers doing a bit of the legwork when it comes to product research, but there’s a bigger issue at play that hampers some, and that’s a lack of education focused on hands-on, real-world, high-performance building. Architecture-and-design school curriculums might benefit from focusing less on conceptual pie- in-the-sky student projects, and more on conventional nuts- and-bolts projects.

Builders can do more

If all of the above happens, it’s still up to the builder to be the last in the long line of people thinking about the details, and putting all of the puzzle pieces together to make a house that will be comfortable, durable, and energy efficient.

Doctors are perhaps the best-known example of workers who must stay current on advances in their field of study, by way of continuing education and medical journals. Why are builders any different? It will take some extra time to sit down with a set of building plans and get familiar with assembly details, read up on new or unfamiliar products, and pay attention to changes in our collective understanding of how all of these parts and pieces perform when assembled, but the payoff is huge.

Building publications like this one, green Building Advisor, and The Journal of Light Construction work hard to deliver relevant, timely, useful, and—most importantly—trustworthy information. You can subscribe to all three for a sum total of a couple hundred dollars per year. Building Science corporation also offers hundreds of deep, well-researched articles completely free of charge on their website, buildingscience.com.

Social media, particularly Instagram, has also grown into a useful tool for anybody looking to expand their knowledge. It’s not searchable in a categorical way, which makes it harder to access specific information on the fly, but it does offer a level of interpersonal communication that’s akin to being part of a passionate club. Instagram connects people across the country and allows anybody with a smartphone to ride shotgun with talented designers and builders who are willing to share their advice, techniques, and failures.

There are also local discussion groups, podcasts, trade associations, seminars—the list is long, and the options are many.

The burden is on all of us as a group, and we need to do this together. If the same installation questions are coming up over and over again, we need to do a better job of finding the answers. If assemblies are failing, we need to take responsibility for the fact that we’re not providing the right information, not making it easy enough to access, or not bothering to look for it in the first place. The availability of quality, vetted information is better than it has been at any time in history. So, what’s your excuse?

Justin Fink is editorial director of Fine Homebuilding and Green Building Advisor.

From Fine Homebuilding #292