Rubble-Trench Foundations

A simple, effective foundation system for residential structures.

Synopsis: The author makes the case for a rubble foundation, a layer of compacted stone capped with a concrete grade beam, instead of the more conventional concrete footing set below the frost line. It’s low tech and less expensive, and it provides the drainage that any foundation needs for durability.

Although it was first used extensively by Frank Lloyd Wright early in the 20th century, the rubble or gravel-trench foundation has largely been ignored by builders since Wright’s time — perhaps because it represents a different way of thinking about what it takes to support a house. The conventional poured-concrete or block perimeter wall attempts to solve a building’s load-bearing requirements in monolithic fashion by creating a solid, supposedly immovable and leakproof barrier extending from a footing poured below frost line to 8 in. or more above grade. But since freezing water expands 9% by volume with a force of 150 tons per sq. in., monolithic foundations are unlikely to survive in frost country unless they include a footing-level perimeter drain backfilled with washed stone, which carries away water that might collect and freeze under or against the foundation wall.

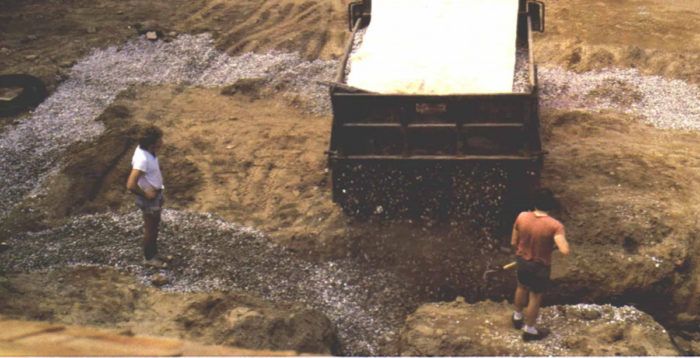

The two functions of load-bearing and drainage are solved separately with a solid foundation, but the rubble-trench system unites these two functions in a single solution: the house is built on top of a drainage trench of compacted stone that is capped with a poured-concrete grade beam. The grade beam is above the frost line, but the rubble trench extends below it, and the building’s weight is carried to the earth by the stones that fill the trench. The small airspaces around each stone allow groundwater to find its way easily to the perforated drainage pipe at the bottom of the trench. Atop the grade beam, a short stemwall of concrete block, poured concrete or pressure-treated wood is built to support the floor framing. Or you can pour a slab. More about this later.

While this foundation system has been time-tested in many of Wright’s houses, acceptance by building officials and the codes they follow is still not assured. In The Natural House (Horizon Press, New York, 1954), Wright speaks of what he calls the dry wall footing. “All those footings at Taliesin have been perfectly static. Ever since I discovered the dry wall footing — about 1902 — I have been building houses that way. Occasionally there has been trouble getting the system authorized by building commissions.”

The disapproval of a building inspector usually arises from a lack of familiarity with the technique, since the Uniform Building Code states clearly that any system is acceptable as long as it can “support safely the loads imposed.” When I first approached our local building inspector with plans for a rubble-trench foundation, he studied them quietly for a moment, ahemmed in good New England fashion, and said, “Yep, that looks as if it oughta work.” And so it will, except in what Wright calls “treacherous soils,” which I would judge to be any soils with a bearing capacity of less than 1 ton per sq. ft.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: