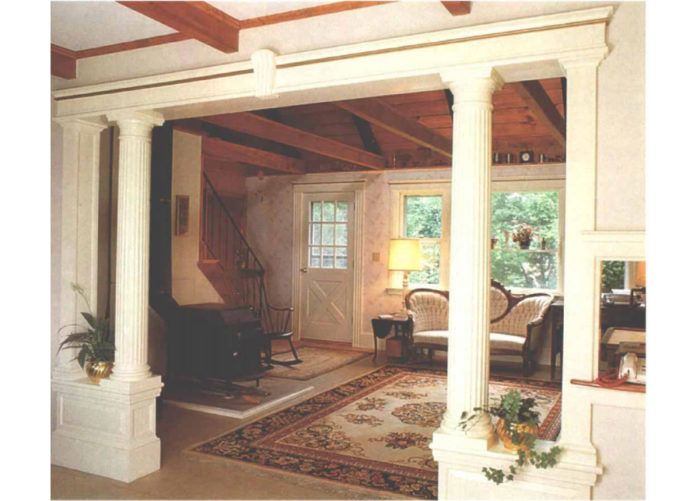

Synopsis: When purchased from a specialty company, classical wood columns are expensive. In this article, the author explains how he made a pair of coopered columns in his own shop. A jig-guided router turns them to shape and cuts the flutes.

Classically detailed columns are commercially available in almost any size and configuration, but they’re expensive, particularly when it comes to custom orders. And because the correct proportioning and form of classical design isn’t common knowledge, local fabrication may not be a practical option. In addition, even a modestly sized column can easily exceed the capacity of most small-shop lathes.

To make the two load-bearing columns, which completed a room divider between our kitchen and living room, I devised a method of turning and fluting column shafts with a shop-built jig that uses a rail-guided router as the cutting tool. Each column has six separately made components. The base plinth at the bottom and the abacus at the top are square sections. Except for the router-turned shaft, the remaining parts were turned on a lathe.

A hybrid design

The columns I designed combine a classically correct 24-flute Ionic shaft with an Attic base, a plain necking and a Roman Doric capital. This hybrid configuration is quite common; it captures the grace of Ionic columnation without the need for a hand-carved Ionic capital, a detail that can overpower the design, the budget, or both.

Classical columns are typically proportioned in modules, with one module equal to the bottom diameter of the column shaft. The module system is more a guideline than a set of inviolate proportions. Every text introduces variations, but there is very little agreement on the details. According to Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, whose Comparison of Orders (written in 1563) is often cited as the rulebook of classical design, an Ionic shaft should be seven modules high (not including the necking, which is typically one more module high), or in this case 49 in. To compensate for the relatively short hybrid capital, and to keep the length of the necking within proportional limits, I increased the shaft height to 52 in. The design of the capital is quite simple and substantially correct, but is detailed to echo the trim at the tops of the adjacent pilasters.

According to tradition, the bottom third of the shaft should be of a constant diameter, while the top two-thirds taper inward. This taper, or entasis, eliminates an optical illusion that makes a straight shaft appear narrowed in the middle. Because the columns are comparatively short, I modified the entasis ratio to avoid excessive taper, which might create an awkward appearance. Vignola gives 5/6 of the module as the correct diameter for the top of a shaft, which in this case would have equaled about 5.83 in. I increased the diameter to eleven-twelfths of the module, or 6.42 in., which I rounded off to 6 3/8 in.

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below: