Energy-Saving Details

A demonstration house in Canada shows new approaches to energy-efficient, environmentally sensitive construction.

Synopsis: This is a good primer on Canada’s Advanced House project, launched in the 1990s to produce energy efficient, environmentally green housing. The project is an outgrowth of the R-2000 Home Program to dramatically lower energy consumption over standard construction.

Canada has the highest energy use per capita of any country in the world. That’s not unexpected, given the country’s climate. In Winnipeg, Manitoba, for example said to have the coldest winters of any capital city outside of Siberia temperatures can drop as low as -48°F. But in summer, temperatures can soar: The highest recorded in this prairie city of 600,000 is 108°F. That kind of climate boosts both space-heating and air-conditioning costs.

During the oil embargo of the mid-1970’s, the Canadian government started the R-2000 Home Program. Houses built to R-2000 standards consumed half the energy of the typical houses being built at the time. The reduction was achieved by increasing insulation, reducing air leakage, improving window performance, using more efficient heating systems and installing a mechanical ventilation system, usually a heat-recovery ventilator (HRV).

But the R-2000 homes still used too much energy. So in 1991, Energy, Mines and Resources Canada started the Advanced House program and proposed building as many as 10 low-energy, environmentally “green” homes across the country to showcase cutting-edge and traditional technologies to chop energy bills to one-quarter of those attributed to a typical house built in 1975.

The program targeted not only space-heating and air-conditioning costs but all energy use, including embodied energy, the amount of energy it takes to produce, manufacture, distribute, install, operate and, eventually, dispose of everything that goes into a house.

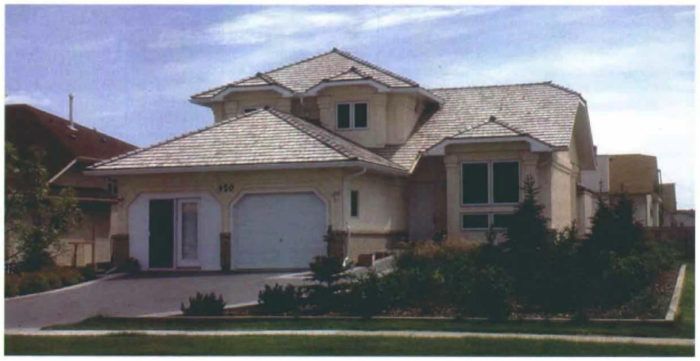

The Advanced House had to be comfortable and convenient to live in, not forcing major changes in lifestyle. And its design had to have market appeal. There’s little point in advancing technology if no one is going to buy and use it.

Energy conservation can be stylish and practical

In the fall of 1992, the Manitoba Home Builders Association was the first group in Canada to construct and open an Advanced House. According to computer simulations, it would cost about $800 a year to heat, cool, ventilate and provide domestic hot water in Manitoba’s Advanced House. That’s far from the $2,400 for a typical 1975 house. Both figures include about $200 a year for standby utility charges, fees to keep electrical and natural-gas lines running into the house.

Monitoring sensors and thermocouples were installed around the foundation and in wall cavities to measure moisture and temperature levels; the performance of the home was scrutinized closely through the fall of 1994.

The 1,859-sq. ft., four-bedroom Manitoba Advanced House demonstrates to contractors and tradespeople that it doesn’t take a genius to conserve materials and energy. To the public, it shows that energy conservation can be stylish as well as practical and comfortable.

Reducing waste and using whiskey bottles

A major concern throughout construction was the amount of construction waste. It’s been estimated that as much as 20% of materials going into landfills is construction waste. Transporting that waste to landfills is an energy cost in itself. Creating landfills eats up valuable and productive land.

“We wanted to reduce the amount of waste as much as possible,” said co-designer and home energy analyst John Hockman of Appin Associates of Winnipeg. So the floor plan was designed to minimize construction-material waste (by using full 4×8 sheets wherever possible, for instance), and scrap lumber was used for blocking. Suppliers were advised that all packaging materials had to be made of recycled materials or be capable of being recycled.

On the roof, pine shakes were used instead of asphalt shingles, which require large amounts of nonrenewable energy to produce. Pine shakes cost about 15% more than asphalt shingles, but they

have a life expectancy of 30 to 50 years, after which they can be recycled.

The fill under the foundation and over the plastic drain pipes, or weeping tiles, is an indication of the imagination used. About 30% of the fill is empty whiskey bottles, smashed and pulverized on-site when tumbled in a concrete mixer with pea gravel. “We expected some problems with sharp edges of broken glass,” said consulting engineer Gary Proskiw, the other designer of the house and head of Proskiw Engineering Ltd., which has extensive experience in residential-energy use. “The only problem we did encounter was the smell. It was like a distillery.”

The ground-up bottles reduced the amount of gravel required: Gravel must be transported, cleaned and sifted, all of which consume energy. So Canada’s energy use was reduced slightly by whiskey drinkers.

For photos and information about energy-efficient heating and ventilating systems, click the View PDF button below.