Q:

Michael Roland is designing a new house and is trying to choose the right wall assembly. It’s down to a choice between a double-stud wall with either batt or loose-fill insulation, or a more conventional stud wall wrapped in a layer of rigid-foam insulation.

“Using exterior rigid foam solves thermal bridging and prevents condensation within the batts in the wall cavity,” he writes in a post at the Green Building Advisor Q&A forum. “Double-wall construction also solves thermal bridging, but what about the dew point within the batts? Won’t there be a condensation problem?”

A:

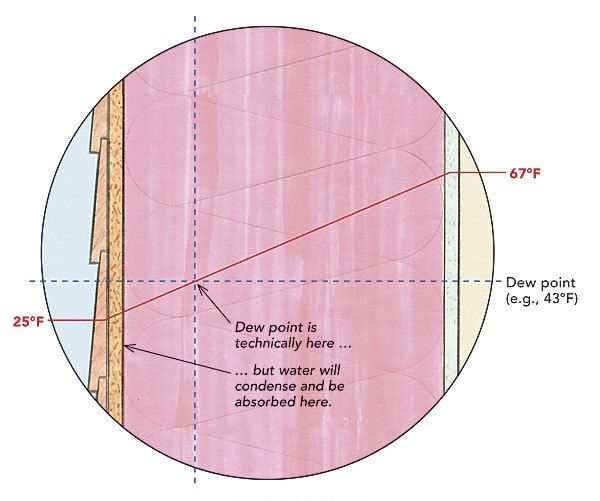

Don’t worry about condensation in batts, writes Dana Dorsett, because it won’t occur. “Condensation doesn’t happen in batts,” he says. “Because batts are extremely vapor permeable, and because low- to mid-density batts are so air permeable, whenever the coldest surface of the cavity framing reaches the dew point of the entrained air in the cavity, the moisture condenses on that surface, not in the fiber itself.” While the condensing surface is picking up moisture, Dorsett adds, “at any other point within the batts, the fiber temperature is above that temperature, so no condensation occurs.”

“If [the condensing surface] is a hygroscopic material such as OSB sheathing, moisture also doesn’t condense, but instead absorbs into the material, never achieving a true liquid state unless there is so much moisture entering the cavity from air leaks that the OSB saturates,” Dorsett writes.

The real risk is that OSB sheathing will rot. According to Jesse Thompson, an architect in Portland, Maine, “A double-stud wall with any type of batt insulation is a high-risk wall system in a cold climate, due to the cold-sheathing issue.”

There are ways of reducing the risk of decay in sheathing, as several contributors point out. One is to use a hygroscopic insulation such as cotton batting or cellulose, which can absorb moisture. “The insulation in contact with the cold surface will absorb moisture, which results in lower moisture accumulation in the sheathing,” Dorsett writes. “Cellulose can take on quite a bit of moisture before saturating and losing R-value, and can store, then rerelease, the moisture as conditions change.”

Thompson seconds the advice. With double-stud wall construction, he suggests careful air-sealing and aiming for blower-door results of less than 1.5 air changes per hour at 50 pascals of pressure.

Another strategy is to use plywood or diagonal-board sheathing instead of OSB, along with a ventilated rain-screen gap between the siding and the sheathing, Fine Homebuilding senior editor Martin Holladay says. Both boards and plywood are less susceptible to mold and rot than OSB. That’s because OSB is made from fast-growing plantation-raised lumber that has a comparatively high proportion of sapwood. Sapwood’s high sugar content causes Joe Lstiburek of Building Science Corp. to refer to OSB as “the Spam of mold food.”

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Disposable Suit

Respirator Mask

Great Stuff Foam Cleaner

View Comments

How is a double stud wall any different from a normal wall with Batts in it (1st reference vs. 2nd reference in the article). If it is filled with the same insulation.

In the first reference we go from a don't worry about it mentality compared to the second reference of a oh crap this is a huge deal!

Isn't a double stud wall technically the same as a normal wall minus the thermal bridge of a stud.

Please sort this confusion out for me

Hammer35,

Since the double stud walls have so much more R value, your sheathing will be colder, thus below the dew point.

If you have a temp difference of 70 degrees, a 2x4 bay with no insulation will have very warm sheathing due to the massive heat loss from the interior through the wall. No rot, but very inefficient. If you add an R13 batt, your heat loss goes down but you will probably still have warm sheathing. If you have a deep cavity with R60 insulation, you will have very little heat loss so the OSB will be almost the same temp as the outside air.