Builders who have been waiting for a new generation of extruded polystyrene insulation with a lower global-warming potential (GWP) than what’s currently available may have to wait a little longer.

On the plus side, Honeywell announced in January it was ramping up production of a new blowing agent, a hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) compound with a GWP of less than 1, called HFO-1234ze. It could replace a hydrofluorocarbon called HFC-134a, whose GWP is 1300 times higher, in the production of extruded polystyrene (XPS).

At the same time, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is finalizing a rule that will ban certain HFCs, including HFC-134a, on Jan. 1, 2017. The agency said the revised regulations, introduced under the EPA’s Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) program, is currently with the Office of Management and Budget for review.

But there are some indications the switch may not be that fast. The XPS industry says the EPA’s timetable is unrealistic and that however attractive a transition away from HFC-134a might be, manufacturers need more time. Further, one industry source suggests the dates proposed by the EPA may be pushed back when the final rule is published sometime this summer.

The situation is a little different for closed-cell spray polyurethane foam. Lapolla Industries Inc., a Texas-based manufacturer, already offers closed-cell polyurethane foam made with an HFO blowing agent, Foam-Lok 2000-4G, and other manufacturers are said to be in the midst of making the transition.

HFOs are a fourth-generation blowing agent

Blowing agents are the chemicals that make insulation foamy and contribute to the foam’s insulating properties. They are used in a number of kinds of foam insulation used by builders–rigid foam sheets, sealing foam sold in aerosol cans, high-pressure foams mixed on site, and low-pressure, two-part foam kits sold in canisters. Variants also are used as refrigerants.

Blowing agents are made in both liquid and gaseous forms, depending on their end use. Gaseous blowing agents are used in the production of factory-made rigid insulation and low-pressure, two-part polyurethane sealant. Liquid forms are for two-part spray polyurethane mixed on site.

The GWP is one of two important environmental benchmarks. A GWP of 1 means the compound is no more damaging to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. The other key consideration is whether a blowing agent depletes the ozone layer in the atmosphere, called the ozone-depletion potential (ODP).

Hydrofluoroolefins are the latest in a succession of blowing agents that started with CFC-11, a chlorofluorocarbon developed in the 1960s and long since phased out because of the damage it did to ozone. Manufacturers later developed HCFCs (hydrochlorofluorocarbons) in the 1990s and then HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons) in the early 2000s as they attempted to come up with blowing agents that had a zero ODP as well as a low GWP.

As Tristan Roberts wrote at GreenBuildingAdvisor in 2011, HFOs are “fourth generation” blowing agents that have both of these beneficial characteristics.

Although the new hydrofluoroolefins were ideally designed to be what Roberts called “drop-in” replacements for HFCs, the various forms of foam insulation are complex blends of chemicals, all of which can interact with each other in unanticipated ways. As a result, substituting one blowing agent for another and making sure the resulting insulation has acceptable working characteristics and thermal properties is a lengthy, expensive process, says Rick Duncan, technical director of the Spray Polyurethane Foam Alliance, an industry trade group.

In addition to Honeywell, whose HFO blowing agents are sold under the Solstice label, DuPont makes one called Formacell 1100 (HFO-1336mzz). Arkema also has developed one called Forane.

Manufacturers have choices other than HFCs and HFOs, including water and flammable hydrocarbons such as pentane. But those materials either aren’t safe for field use, or they produce insulation with lower R-values, so there are some drawbacks.

No timetable for new products

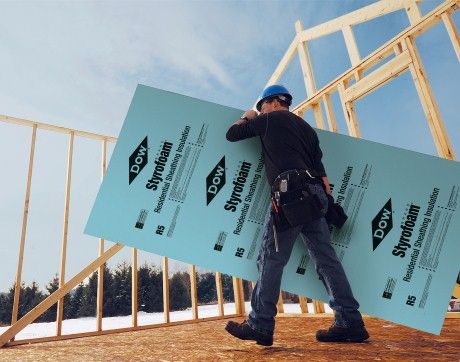

XPS manufactured with an HFO blowing agent has been available in Europe for some time. There are three principal manufacturers of XPS in the U.S.–Dow, Owens-Corning, and Kingspan–and to date none of them has announced a switch from HFC-134a to an alternative.

According to Duncan, the transition to HFO blowing agents for spray polyurethane foam is underway at “many if not all” of the 20 or so formulators of spray polyurethane insulation and roofing systems in anticipation of tougher EPA rules.

In addition to Lapolla, West Development Group, recently acquired by the Henry Company, also has replaced HFC-245fa with HFO-1233zd in its 3-lb. closed-cell foam used in low-slope roofing applications, Duncan said. That’s a denser version of the spray foam used in walls and roof cavities.

The EPA says its proposed rule “would change the status from acceptable to unacceptable” for a number of hydrofluorocarbons, including HFC-134a, HFC-365mfc, HFC-245fa, Formacel B and Formacel Z-6.

But the proposed rule specifically excludes “spray-foam applications” from the 2017 ban, according to a statement from the EPA.

“EPA is continuing to review SNAP submissions for new alternatives including those used in the spray foam end use category,” the statement said.

There’s no telling when the EPA may consider alternatives to the HFCs ready for market, but there may be reasons other than government intervention for switching to an HFO blowing agent in closed-cell polyurethane foam. Lapolla’s website says Foam-Lok has a 10% better R-value than other closed-cell foams, an aged R-value of 6.8 per in. when applied in a 4-in. thickness. It also increases yield from 8% to 10% over previous generation products.

DuPont supports shift, but says EPA’s pace may be ‘aggressive’

In a statement, DuPont said it supported “a consistent, orderly shift to low GWP solutions,” but added that the EPA’s proposed dates for XPS were “considered aggressive and many commenters have suggested moving forward at a slower pace.”

“The final rule is expected in July,” DuPont said, “and dates for specific foam and refrigerant products are expected to be slightly later than originally proposed.”

Helping XPS manufacturers evaluate HFO blowing agents will help sustain insulation products that save energy while lowering their global environmental impact, the company said.

“However, making XPS insulation is a rather complicated and demanding extrusion process,” DuPont’s statement adds, “which makes it difficult to switch from one blowing agent to another. Each company must reformulate its own unique foam systems; design and convert equipment; obtain approval for air permits; and meet internal and external testing requirements…Typically, extruded-polystyrene manufacturers have required five to six years to transition after an appropriate technical solution has been identified.”

In comments submitted to the EPA in October 2014, DuPont said foam producers “have reported as yet unresolved stability problems” with HFO blowing agents. One industry work group looking at low-pressure applications said “this instability leads to reduced shelf life for the packaged foam product…on the order of two to eight weeks, versus the necessary one year or longer needed to meet the demands of this industry’s supply chain.”

Industry trade group also objects

A trade group representing the XPS industry raised a number of objections to the plan in a letter last year. The Extruded Polystyrene Foam Association said the government’s timetable was unrealistic, and that alternatives to HFC 134a aren’t ready for commercial use.

Among the group’s arguments:

- The alternatives listed the EPA as acceptable substitutes for HFC-134a–saturated light hydrocarbons, CO2, water, Exxsol blowing agents and HFO-1234ze, among others–won’t work for XPS, and “the proposed abrupt transition from HFC-134a…is unachievable.”

- HFO blowing agents are expected to cost “significantly more than existing alternatives.”

- It was unreasonable to make the industry rely on a single manufacturer (Honeywell) that produced the new blowing agent in a single factory. “If there is a strike, shutdown, fire or any other type of disruption to production at that plant, or if that manufacturer decides to stop producing that product, the XPS industry might become incapable of manufacturing XPS.”

- The industry made “significant capital expenditures” to switch to HFC-134a just five years ago and anticipated in “good faith” it would be allowed to use it for more than six or seven years.

- Banning HFC-134a on the current proposed timetable would be much more expensive than the EPA has estimated.

John Ferraro, the group’s executive director, said in a telephone interview the EPA has given the industry up to seven years to switch from one blowing agent in the past.

“The process takes years, not months,” he said. “Why they think this one will take only 18 months, I don’t know.

Ferraro said he understood the EPA had amended the 2017 phaseout for HFC-134a in the proposal now under review by the Office of Management and Budget, but added he did not know what the new date was. Should the agency stick with its original deadline, he said, the industry would not be able to comply. “It’s just not possible,” he said.

The group would like to see the required transition pushed back to 2021 or later.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Reliable Crimp Connectors

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Handy Heat Gun

Dow is one of several companies whose extruded polystyrene insulation will be manufactured with a new blowing agent under revised federal rules. But the industry says the proposed 2017 deadline can't be met.

View Comments

Can we get an update on this? what happened with deadlines? Where are we on this?