Drainage Systems

On sizing, laying out and choosing the right fittings for a residential waste system.

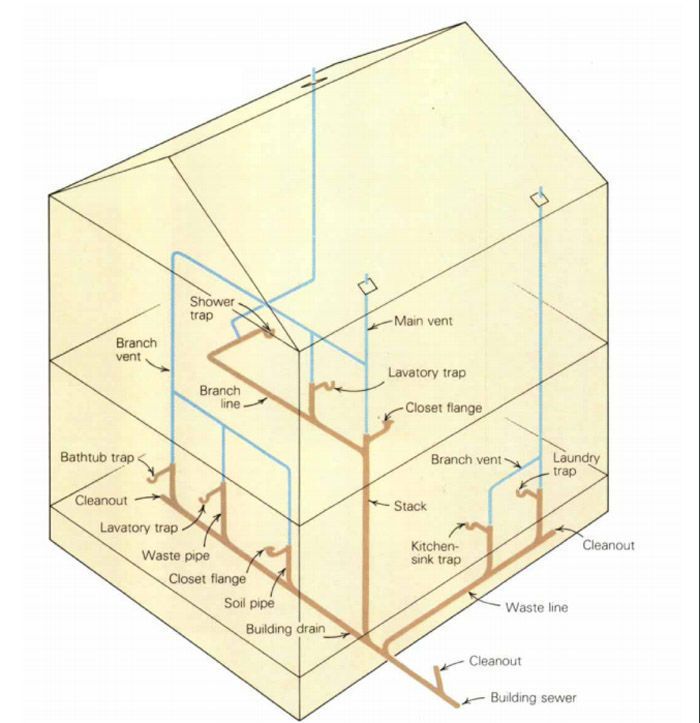

Synopsis: The author likens the waste drain system in a house to a hidden watershed that must be designed and installed correctly in order to provide trouble-free service. He identifies the system’s many parts and pieces, recommends the proper size and capacity of each and explains how they should be connected. Illustrations are a good guide for planning and buying.

A residential drainage system is analogous to a watershed. Each fixture in the house, whether it’s a lavatory, laundry sink or shower, is like a small creek that drains into a larger stream. These larger tributaries eventually merge with the building’s drain, which conveys the household waste to the site’s septic system or to the city sewer lines.

This article is about the procedures I use to size and lay out a residential drainage system. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I do most of my work, plumbers and inspectors follow the guidelines set forth in the 1982 edition of the Uniform Plumbing Code. This code is widely respected within the plumbing industry, and the principles and definitions it lists are reflected in this article.

Drainage-system components

Any discussion of a drainage system has to start with a few definitions so we all know what we’re talking about. Let’s begin just outside the building’s foundation, at the building sewer. The building sewer is a horizontal drain line that connects the building drain with the sewage-disposal system—usually a public sewer line or a private septic tank. The code book defines horizontal as a piece of pipe that makes an angle of not more than 45° with the horizon.

The building drain extends 2 ft. outside the building’s foundation. It is the lowest drainpipe in the building, and it receives the discharge from all the soil pipes and waste pipes within the structure. A waste pipe carries wastes that are free of fecal matter, while a soil pipe carries the discharge from toilets and urinals. A soil pipe may also carry waste from other fixtures.

A branch line is any drainpipe other than a stack feeding into the building drain—a stack is a primary vertical drain line. Vertical means that the pipe makes an angle less than 45° with the vertical, but a vertical pipe is usually as plumb as possible. An offset stack has to be bent to get around some obstacle. If you can bend it at 45° or less, the unit sizing is not affected.

Every fixture in a building has a trap. The trap is the U-shaped pipe that separates the fixture drain from the trap arm. The trap is always filled with water, which keeps sewer gases from invading the house. The trap arm extends from the trap to the vent, and its maximum length is dependent upon its diameter.

A main vent (sometimes called a stack vent, or a vent stack) is the principal artery of the venting system. Its purpose is to provide an air supply to all parts of the drainage system. Without an air supply, waste water traveling to the building sewer could create a suction strong enough to pull the water out of the traps. A main vent extends upward through the building, eventually terminating above the roof. A house will occasionally have several main vents, but it’s best to avoid penetrating the roof more often than necessary. Consequently, many fixtures are connected to main vents by branch vents.

For photos and information on pipes and fittings, and sizing the drain, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Original Speed Square

Plate Level

100-ft. Tape Measure