Flashing Brick-Veneer Walls

Good masonry work blocks most rainwater, and proper flashing details expel what does get through.

Synopsis: Water that works its way through brick-veneer walls can damage underlying wood sheathing or framing. This article explains several flashing details that will protect the structure while allowing water that does get in to escape.

Bricks and mortar may seem impervious to water infiltration, but they are not. Bricks and mortar themselves absorb water. Gaps between bricks and mortar can channel water into the wall of a house. Window and door openings invite in even more water. Most water infiltration can be prevented, but not all of it. So the real key to keeping house interiors dry is the way water flow is managed after it gets behind the brick.

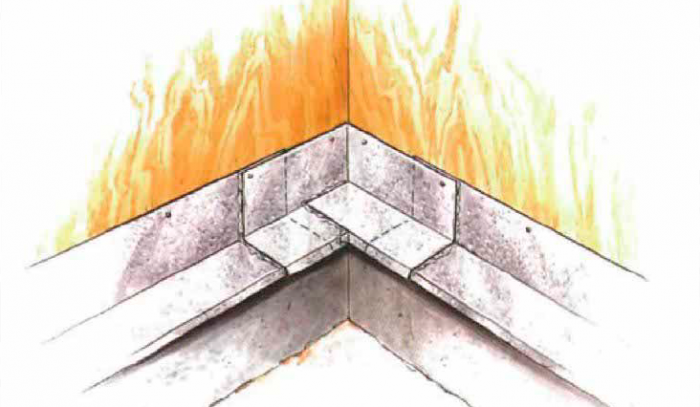

Prior to the 1950s, most brick walls were thick, load-bearing walls consisting of at least two wythes of brick (a wythe is one thickness of brick). The bricks and mortar absorbed water, but usually not enough that it seeped inside. Since the ’50s, most residential masonry walls have been brick veneers, not load-bearing walls. Starting on the outside, modern walls usually consist of a single wythe of brick, a 2-in. drainage cavity, tar paper, wood sheathing and then a standard wood stud wall. Some people use housewrap in place of tar paper; but I don’t because housewrap is not waterproof. Similarly, some people use only a 1-in. drainage cavity, but a 2-in. cavity helps to prevent water from bridging across to the sheathing. The drainage cavity allows water to flow down the back of the brick onto flashings that direct the water back to the exterior.

Prior to the 1950s, most brick walls were thick, load-bearing walls consisting of at least two wythes of brick (a wythe is one thickness of brick). The bricks and mortar absorbed water, but usually not enough that it seeped inside. Since the ’50s, most residential masonry walls have been brick veneers, not load-bearing walls. Starting on the outside, modern walls usually consist of a single wythe of brick, a 2-in. drainage cavity, tar paper, wood sheathing and then a standard wood stud wall. Some people use housewrap in place of tar paper; but I don’t because housewrap is not waterproof. Similarly, some people use only a 1-in. drainage cavity, but a 2-in. cavity helps to prevent water from bridging across to the sheathing. The drainage cavity allows water to flow down the back of the brick onto flashings that direct the water back to the exterior.

At least that’s the plan. Inadequate flashing details allow water to enter the framing, where it can rot the wood, soak the insulation and stain the ceiling or walls. Brick-veneer walls directly above occupied sections of the home (where brick runs over a bay window, for example) are especially susceptible to problems. Any breakdown in the design or installation of the flashing and/or weep provisions of the exterior wall at these locations can cause disaster.

Tar paper and flexible membranes protect the sheathing and openings

As an architect who specializes in fixing failing buildings, I’ve seen a slew of details that don’t work. Here are some details I specify to ensure the longevity of these buildings.

I begin with two layers of #15 tar paper on the sheathing, lapped to shed water downward. The second layer provides redundancy in case of a tear that’s not repaired before the masonry veneer goes up. Peace of mind and fewer callbacks are worth the cost of a second layer of tar paper.

Tar paper alone, however, isn’t enough around windows, doors and mechanical penetrations. Metal flashing and flexible waterproofing membranes are needed to seal these vulnerable openings. These flexible membranes are composite materials, usually containing rubberized asphalt with a cross-laminated polyethylene-film reinforcement. One such product is Bituthene 3000 by W. R. Grace. Some people use Grace’s roofing underlayment, Ice & Water Shield, for flashing, but Bituthene 3000 is a little thicker and stronger. Some manufacturers offer flexible through-wall flashing to take the place of rigid metal. I don’t recommend this because metal is more durable and more easily formed into a drip edge.

For more photos and information about how to properly lay bricks to shed water, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Peel & Stick Underlayment

Hook Blade Roofing Knife

Flashing Boot