Making a Tool Review

The inside story on how Fine Homebuilding decides which tools to test, who does the testing, and what makes a tool worthy

When people find out that I’ve edited several tool-review articles at Fine Homebuilding, I can usually guess the next two questions they’ll ask me. Number one is, “Do you get to keep the tools?” That would be a nice perk, but no, we don’t. Number two is sometimes asked in a cynical tone, as if the questioner wants me to know that he’s already in on the answer, and it’s one of journalism’s dirty little secrets: “You go easy on the advertisers, though, right?” No, we don’t. We aim for fairness and truth.

When I interviewed for this job, Fine Homebuilding’s editor in chief, Kevin Ireton, showed me a letter that he’d received from an advertiser. The letter took the magazine to task over a then recent review of framing nailers (October/November 1996, #105) The review’s authors, Rick Arnold and Mike Guertin, had pointed out what they took to be a flaw in one of this advertiser’s nailers. The letter went on to serve notice that the manufacturer was pulling its advertising from the magazine because of this review.

During the ensuing long day of interviews, that letter came up more than once. While no one I spoke to was happy to lose the advertising, no one even suggested that the authors or the sponsoring editor were wrong to point out a legitimate problem with the tool.

What tools to review?

Our goal when producing tool articles is to provide readers with sound information that will help them to buy the best tool for their needs. We review professional-grade tools that builders would commonly use on job sites, leaving shop tools, such as jointers or cabinet saws, to our sister publication Fine Woodworking. We also factor in whether a tool is one that a good percentage of our readers might buy. For example, as much fun as testing them might be, you’re not likely to see a comparative review of 75-horsepower tracked front-end loaders in Fine Homebuilding.

There are only so many tool categories, and new ones are rare. This fact means that we repeat topics when doing so makes sense (photo 1). An example in the February/March 2002 issue (#145) is “Choosing a Framing Nailer,” again written by Rick and Mike. That topic’s got a lot going for it.

Almost every carpenter owns at least one framing nailer (or wants to), and they’re expensive enough that readers probably would value an informed opinion before buying. However, the last time Fine Homebuilding reviewed them was only five years ago (just before my interview). We’re covering nailers again because many of the big manufacturers claim to have re-engineered their tools to make them more powerful. Also, there are some new players in the field, such as DeWalt and Porter-Cable, and we figure the readers might be curious about their tools.

We’re careful to review only tools available on the open market — no tools that are just scheduled for release. The Bosch 1589 jigsaw is an example of why. In “Jigsaws Revisited,” published in the October/November 1999 issue (#126), the 1589 was author Michael Standish’s favorite tool. For good reason, too, the 1589 is a standout: balanced, powerful, quiet and convenient. Bosch sent it to me along with their 1584 and 1587 saws, saying that the 1589 would replace them both in January 2000, shortly after the article was due to come out. The timing made sense, and reviewing two soon-to-be-obsolete saws without including their replacement seemed dumb, so we included the 1589 in the article. I even called Bosch in August, shortly before #126 went to the printer, to confirm the tool’s debut. “Yep,” they said, “it’ll be available in January 2000.”

Guess what? Early in January, a reader who had contacted Bosch to find out where to buy the 1589 called me. “The fifteen eighty what?” Bosch had said. You can read my retraction in the April/May 2000 issue (#130, p.122).

Limiting the field

A year ago, when we first considered revisiting framing nailers, Dave Ericson, the article’s editor, found that there were something like 40 candidates for the review. He whittled that down to 30 tools, still a huge number. We like to limit the field to 10, maybe 20 tools in order to have space to say something meaningful about each tool. Besides, how do you field test and keep track of more tools than that? We think we found a way in this article, but it was a battle.

In order to make a useful article that’s of a manageable size, we look for sensible ways to limit the field. Size is one way; 10-in. portable table saws, or 12-volt cordless drills. Configuration also works; two recent articles, one on sliding compound-miter saws and one on fixed-head compound-miter saws, spring to mind. “Choosing a Framing Nailer” could have been two articles: “Coil Nailers” and “Stick Nailers.” We didn’t do that because, except for a few standouts, it turned out that a lot of the tools weren’t very different from each other.

“Choosing a Framing Nailer” is structured to dish out its information on several levels. Most of it ended up in two charts, one that detailed all the coil nailers and one that did the same for stick nailers. I’m told by the art department that charts can be graphically ugly devices, but I’ve always liked them, both as a reader and as an editor, because they pack a lot of information into a small space. If you just want to compare prices or relative nail-driving abilities without wading through all the text, the chart allows you to do that.

The main text discusses the various features of the nailers — definitions of sequential fire and single fire, the relative advantages of stick and coil nailers, descriptions of depth of drive adjustments and so on. Several photos work with the text to show readers what words can’t describe well. The text and the photos put the chart into context by telling readers what the chart’s categories mean.

Finally, at the end of the article, is a full page with the information that’s probably what you really wanted from the article anyway — Rick and Mike name their favorite tools and the reasons that made them stand out.

Authors and editors

The editors don’t test the tools. Sure, we play with them during the photo shoot, but the testing gets done by the authors, people who make their living with tools. Editors are mainly facilitators. We’re the official voice of the magazine that contacts manufacturers for the sample tools. We help the authors decide what to write about, take most of the photos and work with the art guys to make a good article layout.

Because we’re immersed in it every day, editors know the magazine better than most authors do. A big part of our job is fitting the author’s text to the magazine. This latter means tone, as well as word count. My boss tells the story of a miter-saw review in the August/September 1993 issue (#83). The author, Jim Chestnut, despised the trigger set-up on one particular saw. Jim wrote an eloquent description of why, which in the original manuscript, he ended with words to the effect of, “The trigger on this saw couldn’t be more painful to use if it had been designed by the Marquis de Sade.” While I’d bet his first read of that description made the editor spew coffee on the manuscript, he wisely decided that the reference was unnecessarily inflammatory and removed the Marquis from the finished article.

Our authors have to be able to try tools out in real job-site conditions. They have to be thorough, inquisitive, mechanically minded people who can cogently describe what they learn about the tools. They need to keep accurate notes on however many tools they’re testing. And the author must be someone we trust, because there won’t be an editor standing over him to ensure that he’s really looking at all of these tools. Finally, the author needs an unbiased eye. We wouldn’t commission an employee of a tool manufacturer, for example, to write a tool article.

Getting the tools

Okay, we’ve decided the category of tools and the author. It’s about six months until the issue goes to the printer and it’s time to approach manufacturers for tools. At this point, the editor calls all the tool manufacturers that he knows of, even those he doesn’t think make that type of tool, just to be sure not to miss any. Most manufacturers are happy to work with magazines and will lend us the tools. Many don’t even want the used tools back, but it’s our policy to return them or to buy them. If you knew that an article’s author or edit or had a basement full of free tools from the XYZ Tool Co., would you trust the magazine’s rave review of XYZ’s widget? I wouldn’t.

Occasionally, a manufacturer will decline to participate in one of our reviews. If there’s a good reason, say, the current tool is being replaced and the new version isn’t yet available, we’ll note that in the article. There is only one manufacturer that regularly declines, and if we’re sure that their tool belongs in the article, then we’ll go out and buy one. As you might guess, this tack doesn’t always sit well with manufacturer. The readers seem happy, though.

Now, you might wonder if manufacturers take this opportunity to send us ringers; specially tuned up or selected tools? We wonder that too, but our conclusion is that they don’t. We think this because we regularly receive tools that have manufacturing defects. If they’re sending ringers, they’re doing a lousy job. The potential for ringers is another reason that we hire authors who use tools for a living. Most tradespeople will have a pretty good idea of the normal levels of fit, finish and performance of new out of the box tools. Deviations from the norm should raise a red flag.

What do we look for?

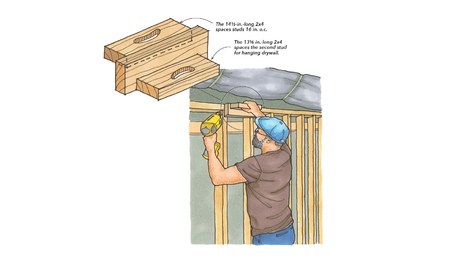

One thing we can’t test for is durability. We simply don’t have the facilities. What we can do is get the tools into real-life use for a month or so. We work with the author to devise tests for power and accuracy. He might fire nails into an LVL header to see if the nailer sets them consistently. He might count the screws a screwgun sinks on a battery charge and check cuts for square. Frequently, he’ll borrow our decibel meter and check the sound level produced by the tools.

Beyond that, our tests are subjective: How’s the balance? Are the controls convenient to use? How about if the user is wearing gloves? We want the author to tell you what he likes and doesn’t like about a tool. But because our reviews are subjective, we also want the author to say why he doesn’t like that feature. We figure this extra tidbit of information gives you a means to weigh the author’s opinion.

It attracts attention when one of our authors shows up on site with 30 framing nailers or a dozen circular saws in the back of his truck. “Figuring on framing the whole house by yourself today?” “Got one for me?” We encourage authors to let others try out the tools. While we want the article to reflect the author’s opinion, comments from his coworkers can broaden its view.

What if there’s a problem?

Sometimes our authors break tools or find some particularly nagging problem. What we do when that happens is a judgment call. If the problem is clearly a design flaw, a description of it goes into the article. If it seems likely to be an isolated manufacturing defect, we call up the manufacturer, explain the problem, and ask for a replacement tool to continue testing. To be fair to both the manufacturer and to the readers, we’ll usually mention in the article when this situation occurs.

Laying out the article

Even before the text and the photos are in house, the sponsoring editor and art director are collaborating on the article’s layout. However, the real work begins about four months before the printer’s deadline, when the editor starts to edit. We go over the manuscript line by line, shortening and clarifying. We pick photos and write captions and decide if drawings are needed. When the sponsoring editor finishes his edit, the text goes to the managing editor and the editor in chief for review. Once these guys are happy, the text goes to the copy editor for a grammar and style check, and then back to the author for his approval. When the author’s happy, the article goes to layout, at which point there’s another round of fact checking and maybe some more line editing to fit the text to the layout.

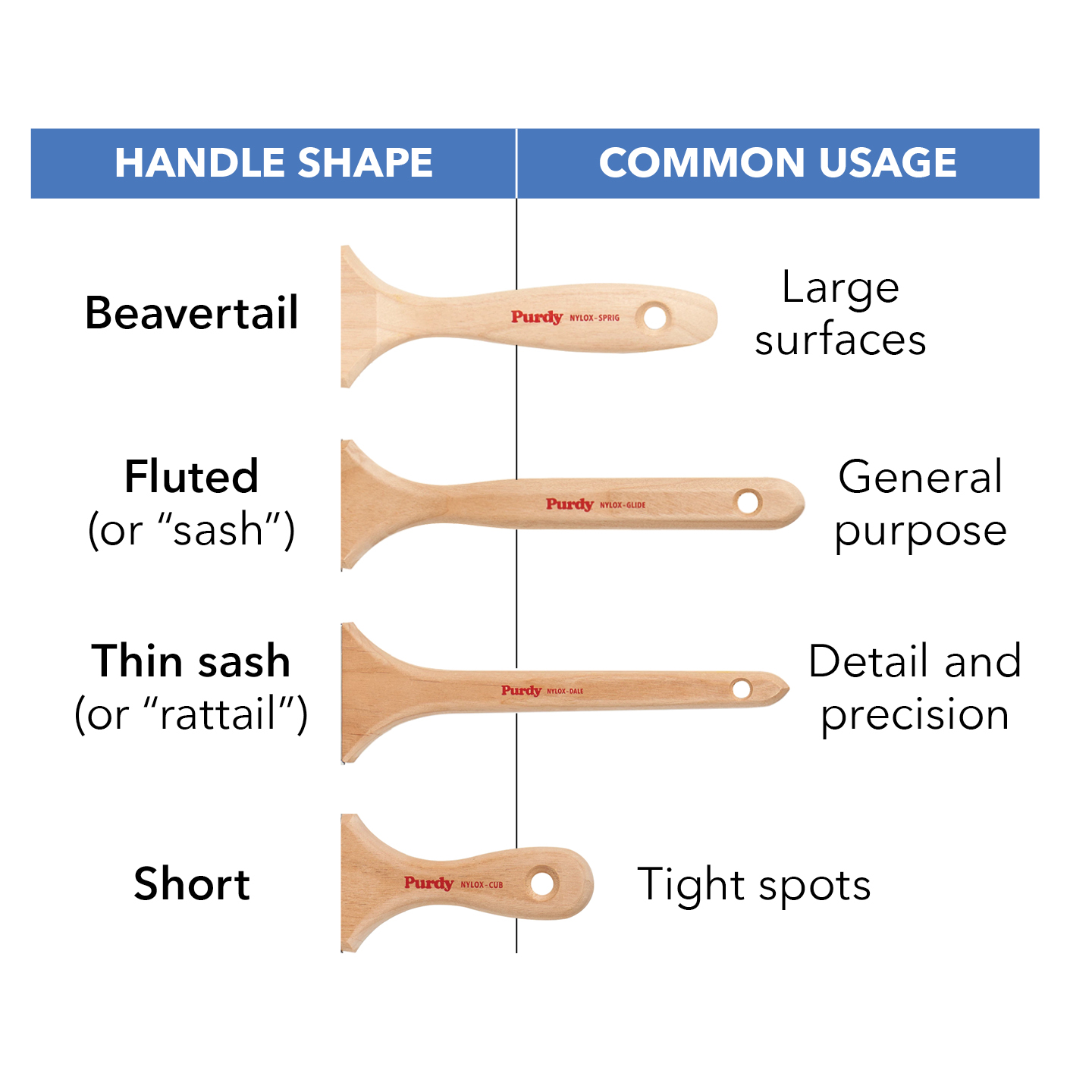

Fine Homebuilding tries to make it easy for readers to get the information they want. With tool articles, we’ve usually done so in one of two ways, baseball cards or charts. “Baseball cards” is our jargon for an article layout that has a photo and a paragraph or so of text about each tool. Baseball cards work well when there are a limited number of tools. We can fit in some useful discussion of each tool, and reference the photo to describe the tool’s features.

The second layout approach, charts, usually isn’t pretty. But it gives us a means to provide a bunch of information in a small space, and it’s the approach we use when there are numerous tools. Sometimes, we’ll use both baseball cards and charts.

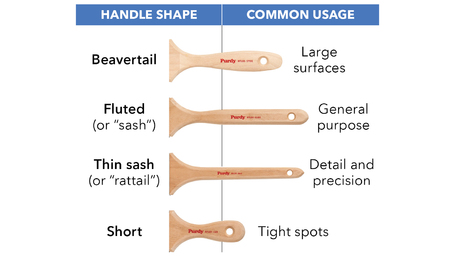

Often, we’ll find a tool that’s related but that doesn’t quite fit the mold. If there’s space, we fit it in a sidebar. We’ll do the same thing for accessories and special safety concerns, as well. Sometimes, there’s no space left in the article and we’ll run ancillary items in one of the departments, such as Tools and Materials or What’s the Difference. You’ll find examples like this in both of those departments in the February/March 2002 issue (#145).

That’s the short description of how Fine Homebuilding makes tool articles. I left out a lot of boring stuff, such as fact-checking prices (that’s one you might want to know — I search online first, then check catalogs, and use the lowest price that I find), model numbers, amps, phone numbers and so on. Then there’s the tedium of boxing up the tools and returning them to their manufacturers. I have to confess that I’ve had a pile of cordless reciprocating saws awaiting boxing in my office for months. If I hold out for six more, I can get the summer intern to do it.

Andy Engel is executive editor of Fine Homebuiding.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Hitachi Pin Nailer (NP35A)

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Heat-Shrink Tubing