Any building scientist worth his energy-modeling software can tell you that uncontrolled air leaks lead to a variety of problems in houses, including increased energy consumption, lower comfort, and the possibility of moisture condensation inside walls and ceilings.

That’s why builders who specialize in superefficient houses spend so much time tracking down and correcting air leaks. The process can involve a number of materials and sealants, such as special gaskets, tape, and caulk, plus a lot of time and attention to install them correctly.

In the end, builders see how well they’ve done with a blower-door test, which measures how leaky the building envelope is with the aid of a powerful fan. If you’re seeking Passivhaus certification, a fan pressure of 50 pascals can induce no more than 0.6 air changes per hour. That’s very tough to achieve.

If air-sealing seems like a specialized skill beyond the reach of many builders, help is on the horizon in the form of technology originally developed to seal air ducts. When fully developed and commercialized, the process could turn air-sealing into a speedy, routine operation.

Technology developed at University of California

According to an account by Daniel Mathews at EarthTechling, this story starts at the University of California-Davis, which invented a process 16 years ago for sealing existing ductwork. It was later marketed by a startup company called Aeroseal.

A fine mist of sealant is forced under pressure into ducts. The sealant gravitates toward leaks as it tries to escape and eventually plugs them up. The process is not unlike blood clotting at a wound.

The inventor, Mark Modera, director of the university’s Western Cooling Efficiency Center, wondered whether the same process could be used to seal whole houses, Mathews wrote. It was tested on three Habitat for Humanity houses being built in California.

“In these ‘already-sealed’ houses, it reduced leakage by about 50%,” Mathews said. “(WCEC has already developed monitors and software that graph the whole-house leakage rate in real time, while they are sealing it.) Before commercializing the technology, they plan to refine it a little more, hoping to reach leakage rates too small to measure. Remember that the sealant has been effectively sealing ducts for 12 years already.”

Not for furnished, occupied houses

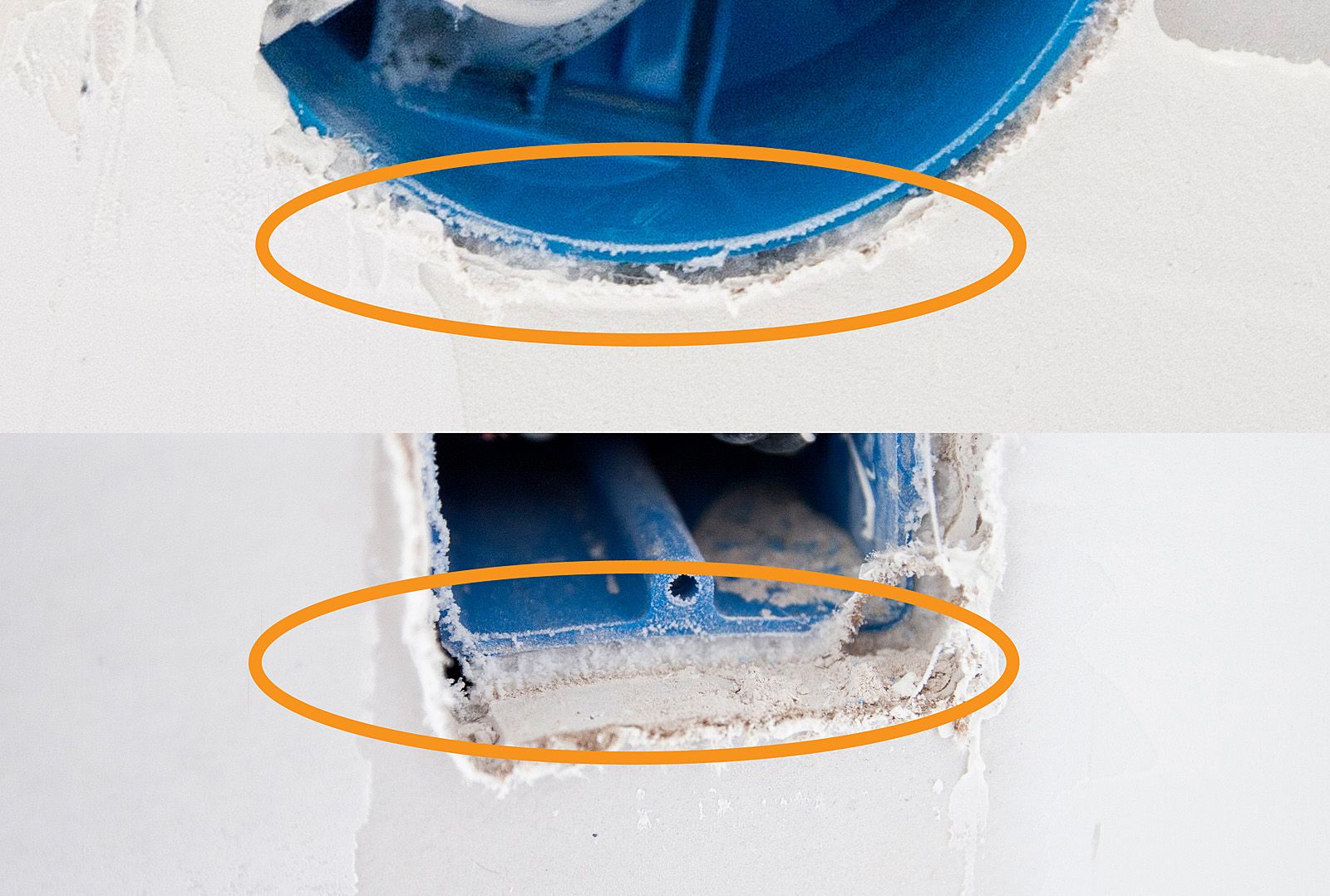

When the house is ready for sealing, a blower door is set up. In the center of each room in the house, workers mount a nozzle capable of producing a fine mist and connect it with a supply line to a container of liquid sealant. Then the house is pressurized with the blower-door fan.

As the house becomes pressurized, air is forced through holes and gaps in the building envelope, carrying some of the sealant mist with it. Just as the compound seals leaks in air ducts, it plugs holes in the building.

No one is inside the building during the procedure, so they won’t have to breathe in any of the sealing compound. Once the material has solidified, Mathews reports, it is considered nontoxic and even low-VOC.

But Modera says the process is best suited for new houses or houses that are empty.

“We tried it in an existing home,” Modera told a reporter for The Record in Stockton, Calif. “I don’t feel comfortable thinking about doing it when there’s all the furniture in the house, but when someone moves out and you have an empty house, I think it will help.”

Treating occupied houses may be possible in the future, he told the paper, but it may be a year or two before the process is ready for commercial use even in new houses.

Testing process on Habitat houses

Three Habitat for Humanity houses in Stockton have been air-sealed with the process through a grant from the California Energy Commission.

After construction workers went through the houses to seal obvious air leaks with caulk, the houses were pressurized and misted with sealant, reducing leakage by an additional 50%, according to the newspaper.

It took about an hour to seal each 1200-sq.-ft. home. Workers monitored progress from the garage via cameras located in each of the rooms.

“We get a kind of laboratory to do our tests,” Modera said, “and they get their homes sealed up. Everybody’s happy.”

In theory, no limit to the process

Once fine-tuned, the process should substantially reduce the amount of time and effort builders spend on air-sealing a house with conventional tools and materials, says project manager Curtis Harrington, and potentially eliminate it completely. “In theory, we can seal any size hole,” he says. “It just takes longer.”

While the sealing is taking place, the blower door is providing “continuous feedback” on how tight the house is getting, Harrington says, and researchers now typically stop when they’ve run out of sealant.

Researchers are currently experimenting with a modified version of a water-based acrylic sealant made by Tremco but plan on testing several types.

How tight can the process make a house? Harrington says it should be possible to get blower-door results of 1 air change per hour at 50 pascals of pressure. That’s not a Passivhaus result, but it’s a very tight house.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Handy Heat Gun

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Affordable IR Camera

View Comments

What happens to the excess material?

How does it affect flooring (carpet, hardwood) and painted surfaces?

Is it easy to clean off a window?

Very Interesting - and promising.

As your aware half our annual heating costs are attributable to air leakage.

Our city building bylaw requires all new houses have a max. air leakage req. of 1.5 ACH(certified by an independent blower dr. test.)We presently have several builders airsealing under.5 ACH. This technology could bring it close to ziploc bag airtightness.

Add a balanced HRV and the owner would have an extremely efficient,comfortable castle.

Question: Are you presently using waterbased acrylic or is that what you may use in the future. If not what are you using?

Thanks for all the leading bldg. science articles.

r.w.h.