Energy Modeling Has a Very Fast Payback

An architectural and engineering firm tracks how quickly modeling pays for itself in a variety of commercial building types

Energy modeling for commercial and institutional buildings is expensive, but a study by an architectural and engineering firm finds that the payback is “shockingly short”—in some cases, just a month or two.

A post at the website of the Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, part of the U.S. Department of Energy, describes research by Anica Landreneau, director of sustainability consulting at HOK. Landreneau wanted to learn how long it took to pay off the cost of energy modeling through lower energy consumption. Over a period of several years, she tracked energy-modeling costs and predicted energy savings for a number of HOK projects.

Energy modeling lets designers calculate how much money they can save in lower energy bills by investing in various building features—what are called “energy conservation measures.” For large buildings, the report says, the costs of modeling can be as high as $200,000, but it’s apparently money well spent. By identifying unnecessary features such as oversize HVAC systems, modeling can sometimes pay for itself even before construction ends and the building is occupied.

Energy modeling is a ‘no-brainer’

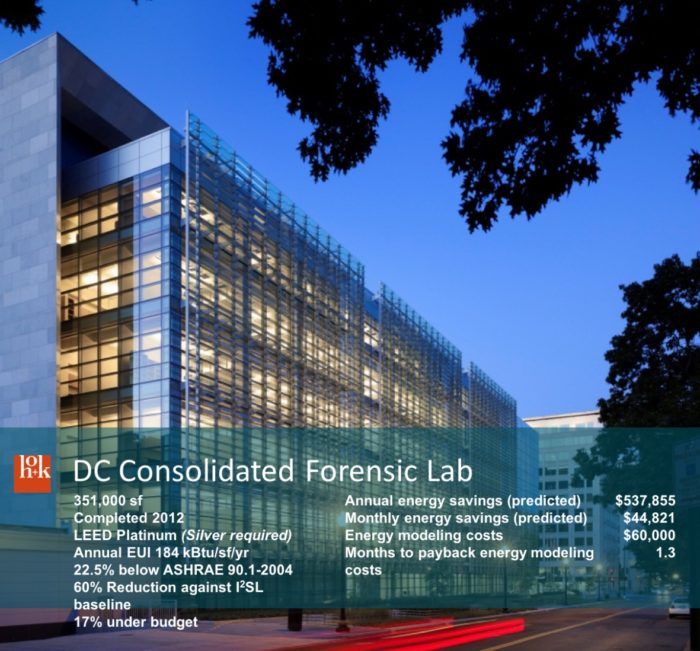

In one example, the construction of a forensics lab and morgue in Washington, D.C., the cost of modeling was $60,000, with a payback of 1.3 months. Features such as hydronic heating and cooling and a dynamic building facade controlled by an on-site weather station helped. In another instance, energy modeling that helped develop a means of using seawater and captured trade winds for cooling a building in Hawaii cost $170,000 but paid for itself in 4.4 months, according to HOK research.

Even with hefty price tags, energy-modeling fees represent a small percentage of overall building fees—often less than 1%. At one building in the HOK study, a regional hospital, the cost of the modeling was 2.4% of gross fees, but it resulted in annual energy savings of $3.3 million—a one-month payback.

Landreneau presented the findings in Washington at the Better Buildings Summit earlier this month.

“Energy modeling is a no-brainer for HOK, and we believe for our clients,” she said. “It’s like reading the mpg (miles per gallon) rating before you buy a car. It’s basic performance information every building investor should know. Energy modeling on all our projects helps HOK meet our internal energy and carbon commitment (AIA 2030), helps our clients find cost-effective ways to meet their sustainability goals, and supports a more creative, beautiful, and resilient design outcome.”

Although Landreneau said that engineers are capable of designing energy-efficient buildings without computer modeling, building owners and project managers want more. “They demand to see numbers,” she explained, so the modeling is useful for getting energy-saving features into final designs.

Whether similar results are possible for energy modeling in residential construction isn’t addressed in the HOK study.

Marc Rosenbaum, director of engineering for South Mountain Corp., hadn’t thought about the issue in exactly those terms.

“I do think it helps guide where the next money is most productively spent to save energy, once the house meets code and has enough thermal integrity to not cause ice dams, etc.,” he said by email. “Most of the modeling I do these days supports the design of zero-net-energy homes. Once the house is superinsulated, more energy goes to hot water and plug loads, so deadly accuracy of heating energy is less critical.”

Read more: http://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/green-building-news%2A#ixzz49gwB5f3D

Follow us: @gbadvisor on Twitter | GreenBuildingAdvisor on Facebook

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Original Speed Square

Musings of an Energy Nerd: Toward an Energy-Efficient Home

100-ft. Tape Measure