A Trip to the Cedar Shed

A seasoned carpenter reminisces about the days before fiber-cement siding, but acknowledges that wood clapboards come with plenty of complications.

This is the extended version of the print version in Fine Homebuilding magazine April/May 2019, issue #282:

As my crew and I recently clawed and coughed our way through another fiber-cement siding job, I yearned for the days when most of the siding we installed was cedar. Not that siding is ever much more than drudgery—measure, cut, nail, repeat—but in times past it was possible, if the pump jacks behaved and the weather was mild, to feel something akin to pleasure while nailing up red-cedar clapboards.

There was the fragrance, of course, and the amazing strength-to-weight ratio; passing a twenty-footer up to a second-story scaffold was nothing. And talk about workable! If you were perched high against a gable you could cut the stuff with a handsaw and tweak the fit so readily with a block plane that it left little excuse for caulking.

Redwood was disappearing from local lumber yards on the East Coast when I broke into the trade in the mid-70s, but western cedar remained available and reasonably priced for another decade or so. In my hometown on the bank of the Hudson River, there happened to be a large distribution yard that had been hastily built during WWII to supply lumber for the war effort. The gargantuan scale of the place gave it an otherworldly atmosphere. Towering high above was an abandoned bridge crane that bestrode the yard like a frozen colossus, dwarfing even the big double-axle forklifts that scurried about at its feet.

One of the yard’s cavernous sheds was devoted exclusively to cedar siding, and I would go there occasionally to pick up orders. The cedar shed was presided over by a 6-ft. 4-in. hulk of a man who spoke with a strangely musical backwoods accent so thick I could barely understand him. He was built like a heavyweight prizefighter, and he took his job just as seriously. Now, as anyone who frequents lumberyards knows, there’s a certain cat-and-mouse game that governs relations between contractors and yardmen. The contractor wants the clearest boards in the pile, or, in the case of random-length products, he wants all long lengths to minimize waste. The yardman, meanwhile, gets a mixed message from his boss: don’t indulge the contractor too much (thereby downgrading the material that gets left behind), but cut the guy some slack if he’s a regular. Such diplomatic tightrope-walking does not come naturally to your average lumber handler, but, whether by instruction, imitation, or some mysterious osmosis, a code of behavior seems to get passed from one generation to the next. So while the contractor schmoozes the yardman as best he can, hoping to swap out just one more ugly board, the yardman sets the clock ticking on a well-rehearsed protocol that starts with cordial pleasantries, shifts into bored indifference, and, in the case of exceptionally picky adversaries such as yours truly, eventually freezes into strained silence. If the contractor overplays his hand completely there will be a blunt protest from the yardman and a threat to complain to his foreman. Knowing how to extend this little pas de deux to the brink and no further requires nerve, imagination, and lots of practice on the part of the contractor. At the time of this encounter I was well-endowed with the first two but still deficient in the latter.

On this trip, the boss of the cedar shed eyed me with suspicion from the moment I arrived. As I dug out the 16-ft. and 20-ft. bundles in the pile, he began to grumble and shake his head. I backed off, throwing a couple of eight-footers on the truck. He countered by tossing on packs of four-footers, which he handled like toothpicks. A frown clouded the man’s face as he calculated the effects of my initial greediness on the proper mix of lengths. I tried distracting him with small talk, but he would have none of it. We had loaded most of the required footage when I sensed that it was now or never; I resumed piling on the long stuff. The customer is always right, right?

That’s when the pot started to boil. Chortling noises erupted from the yardman, and his red-rimmed eyeballs started to oscillate. His movements grew punchier and perspiration glistened upon his brow. Soon an ominous rumble began to emanate from the back of his throat like the sound of an approaching forest fire. “How ’bout that Reggie Jackson?” I stammered, feebly trying to tamp down the impending conflagration. The rumble turned to muttering and then to shouting. Seeking an outlet for his mounting fury, the offended giant picked up 10-ft. and 12-ft. bundles and hurled them onto my truck like cordwood. My eyes scanned the shed for the nearest exit. Could I outrun the guy? Maybe I could jump in that dumpster and hide. Finally I just froze like a deer caught in headlights.

Transfixed, I watched the yardman tally up the load, a vein pumping wildly in his temple. Eighteen feet short. Our gazes locked and he glared at me for what seemed like an eternity. Registering the surrender in my twitching face, the yardman’s eyes abruptly narrowed. With a snort of disgust, he flung a twenty footer on top of the load and dismissed me with a sharp flick of his head. I scrambled into the cab and fled in a cloud of exhaust, the squeal of my tires echoing off the walls of the cedar shed.

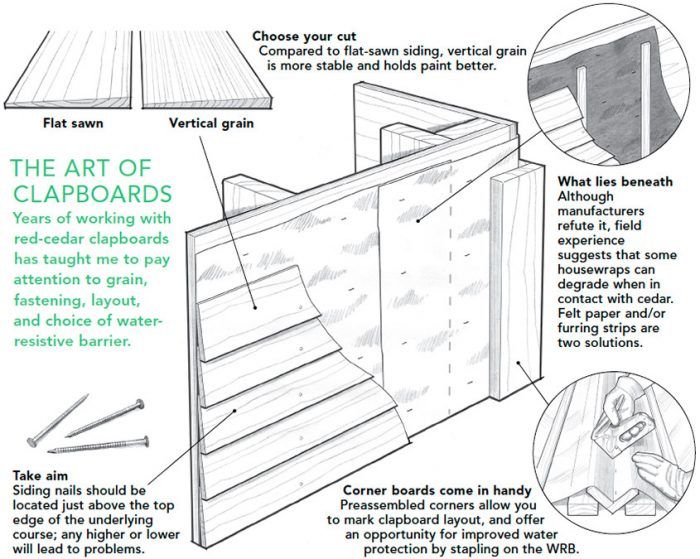

In spite of cedar’s many admirable qualities as a siding material, it has its drawbacks. The grain of flat-sawn cedar can peel, especially in strong sunlight. Flat-sawn boards also experience twice the seasonal expansion and contraction of vertical-grain boards, which makes paint more likely to peel. The additional cost of vertical-grain siding seems well-justified by these differences. The increased movement of flat-sawn siding boards also makes them more likely to buckle or split if a nail is accidentally placed too low, thereby restricting the movement of the course underneath.

To increase the paint-holding ability of cedar siding, you can put the rough side out if aesthetics permit (most cedar products have a smooth-planed side and a rough-sawn side). The rough texture causes a thicker coat of paint or stain to be deposited, and the hairy surface fibers bind the paint film together. For new construction, another good way to extend paint life is to purchase factory-prefinished boards. Not only will the boards be painted under ideal conditions, but the wood surface won’t suffer any of the ultraviolet degradation that can occur on a job site as siding waits to be painted. If prefinishing isn’t feasible, the boards should at least be primed on site with a roller before installation. All field cuts should also be primed. Oil-based primer is still the best for sealing in extractives (natural chemicals found in cedar, also called tannins) that might otherwise bleed through, especially with a light-colored finish paint.

Speaking of extractives, there is an ongoing debate about whether cedar tannins cause premature deterioration in Tyvek housewrap. Anecdotal accounts say yes. Both DuPont (makers of Tyvek) and the WRCLA (Western Red Cedar Lumber Association) say no. That said, DuPont recommends using DrainWrap (the crinkled version of Tyvek) or a rainscreen system (such as furring strips) under cedar siding. By rapidly draining away infiltrated water there will presumably be less opportunity for tannins to contact the housewrap, not to mention all the other advantages of a rainscreen. Furring strips add expense, though, if only because exterior casings must be built out to accommodate the added thickness. Using builder’s felt instead of housewrap as an underlayment is another approach, since #15 felt has proven itself for over a hundred years with cedar siding.

For a first-rate cedar siding job, there’s really no substitute for a small-head stainless-steel ring-shank nail, especially where a transparent or semitransparent stain is used instead of paint. Even hot-dipped galvanized nails can react with cedar extractives to cause staining. Copper flashing will also stain in contact with cedar, so if that’s a problem consider other types of siding or flashing.

As for installation, there are a few tricks that can speed up the job. One is to lay out the course spacing on your corner boards before putting them up. As long as the bottoms of the corner boards are mounted at the correct elevation, either by measuring off the top of the foundation or by shooting with a laser, you won’t lose time measuring course spacings as you go. First assemble the individual boards into L-shaped units. Typically each unit consists of a 5/4×6 ripped 4-1⁄2 in. wide that gets nailed to a 5/4×4. Then rack the units on sawhorses with their bottom ends aligned and transfer layout marks from a story pole across the entire set. Transfer the marks to all exposed edges. Check the as-built height from bottom-of-siding to soffit at all corners of the building and make any necessary adjustments. I also like to fold a 4-ft.-wide strip of housewrap along the back of the corner board for its entire length and staple it. These preassembled corner units are then easier to integrate into the field housewrap.

There’s no denying that the high price of cedar makes synthetic siding more attractive. The man-made stuff also comes in uniform lengths, so there’s nothing for contractors and yardmen to argue over. In future ages, when carpenters have nothing to do with trees anymore, all our trips to the big-box store will be bland and predictable—like fiber cement.

Scott McBride is a builder and writer in Virginia. Drawings: George Retseck

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Affordable IR Camera

Handy Heat Gun