Working With Old Wiring

Careful testing is your hedge against frayed insulation, faulty splices and missing ground wires.

Synopsis: The author, a master electrician, details common wiring problems that may be revealed in remodels of older houses and explains how to remedy them. Testing equipment is crucial in identifying hazards that can pose serious safety risks to anyone working around old wiring systems. The author covers the basics, and explains when a qualified electrician should be called in for help.

He died. No joke. He was standing outside the house, next to a slab where the air-conditioning compressor sat. He wasn’t there to fix the compressor, just to paint some trim. Despite an internal short, the compressor worked just fine. But an additive in the concrete had corroded conduit running through the slab, so the compressor was no longer grounded. When the painter touched the compressor, 120v ran through him to ground.

Mostly, it’s 120v, ordinary household current, that kills people — not high-tension wires, not industrial power. In 1991, close to 40% of all single-family homes in the United States had been built before 1940, according to the National Association of Home Builders. Assuming the work was done to code, these houses were wired with a version of the National Electrical Code at least 24 editions behind the current standard, with methods and materials equally antiquated. Forty years is long enough for equipment to deteriorate, and plenty long enough for person after person to have made misguided attempts to update the wiring.

When working in and around an older house, any one of these factors is reason enough to look carefully for electrical hazards. Moving walls, replacing light fixtures and updating receptacles all bring builders and remodelers face-to-face with potential wiring problems. I’ve been an electrical contractor for nearly 20 years, and been certified as an inspector and plan reviewer for more than ten years. So I’ve done a good deal of troubleshooting on old wiring. If safe practices could be distilled into a few rules of thumb (and there are risks in trying to oversimplify this), my list would include these three: Learn how to test circuits correctly; make no assumptions about wiring without testing; and know when to back off and get the help of a qualified electrician familiar with old wiring.

Start with a basic kit of testing tools

The electrician is coming tomorrow to redo things, and meanwhile, the carpenter has this wall between bedrooms to remove. At the main panel box, all circuits are on except for the one that’s marked “Bedrooms.” Wall switches are on, and the outlet at the end of the cable in the wall is dead. Can he cut the line to get it out of the way? Should be safe. Zap!

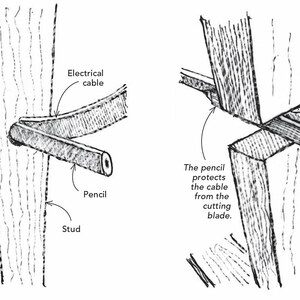

If an outlet is dead, it does not mean that the outlet’s box is dead or that a cable appearing to lead to the box is dead. It’s dangerous to assume that the outlet represents everything in the box. Or that the black wire is hot and the white is neutral, as is most commonly the case. Nor can you assume that the lack of a ground wire means that a box is not grounded, or that the presence of a bare wire means that it is grounded. In short, you can bank on nothing.

For purposes of working safely, all you really have to do is test for voltage in a circuit that you’re about to work on. The basic toolkit is simple. It should consist of some kind of measuring device and a good extension cord that can be plugged into an outlet you know to be working. That’s not a big tool kit, but then the most important tool used in testing is your brain.

For more photos, illustrations, and details, click the View PDF button below: