“I’ve been havin’ some hard travelin’, I thought you knowed.”

Woody Guthrie

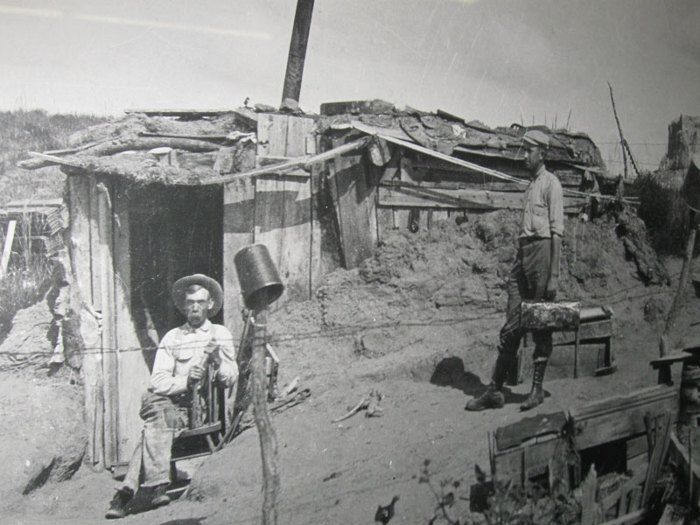

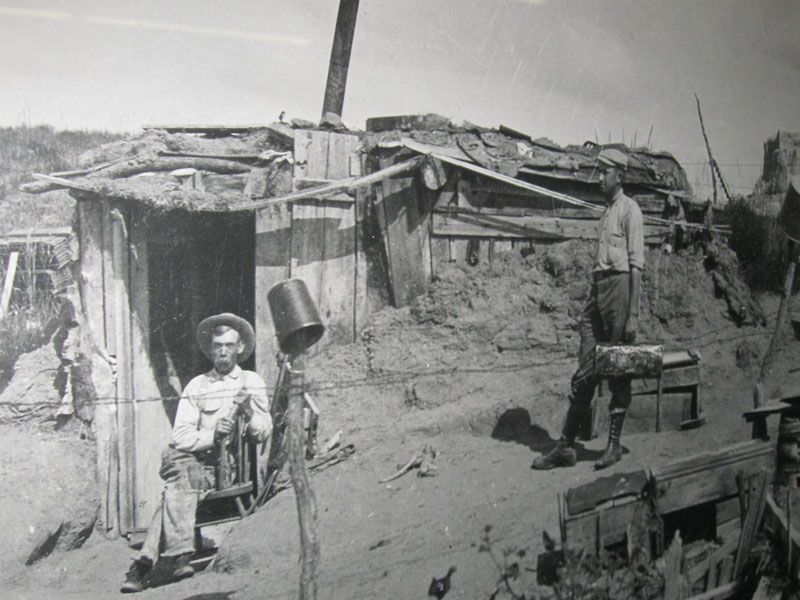

Dugouts were still around until I was in my teens. I used to visit an old man who lived in one when I was out riding my beloved pinto horse. I was working for a rancher, looking for some of his cows that might have strayed down along the White River. His name was Charley and he lived in a home dug back into a bank along this River up until the late 1940s. He lived alone and worked now and then for ranchers cleaning chicken coops, painting a shed, fixing fences. This gave him a little money for food. His rent was free!

I got to know him some over a period of several months always stopping by to say hello. One day he invited me in for a cup of coffee. In the west, you don’t refuse that kind of an offer no matter who it comes from. Once my eyes became used to the darkness, I saw that his place measured about 10 ft. x 10 ft. His table and chairs were tree rounds cut from a nearby cottonwood. His bed was a pile of rags in a corner. On the small, iron stove sat a tea kettle, a frying pan, and a coffee pot. The orange crate cabinet held a few dishes. He reached for a couple of cups, wiped them out with another rag, and poured us both a hot cup of coffee.

I could feel his loneliness as he told me part of his story. He used to be a painter living in San Francisco with a woman who “did him wrong.” I never had the chance to get the woman’s side of the story. Once she left, he drifted north living in Washington and then Montana for a time. And now here he was, heartbroken, living out his days in a place little better than a rabbit hole. He showed me a couple of figures, cowboys on horses, he had drawn with charcoal on butcher paper. I held them to the light and gave him praise. He died that fall when I was back in school. They buried him on the prairie far from any kin, another unknown resting in a different type of dugout.

I never told my mother I visited him in his place. If he had bed bugs, they must have preferred his blood to mine and, lucky for me, I didn’t bring any home.

Life in those ‘great depression’ times really was hard. Unlike today, class distinctions were practically non-existent. Everyone I knew was poor, struggling to keep food on their tables and clothes on their backs.

Hard times then and now seem to breed two types of people. Some become more generous, willing to share what little they have. Others seem obsessed to find someone to blame for their troubles. Sound familiar? It was during the 30s that there was a big resurgence of Ku Klux Klan activity all across the prairie states. What do you do when there are no Jews or Blacks around as the focal point for your frustration and hatred? That’s an easy one. We were the only catholic family in the entire county.

What happened from all this is a powerful childhood memory that I can now look upon as a gift, a blessing. I was near five years old when some of our neighbors burned a cross in front of our home. I was scared, hiding behind my mother’s skirt! At school, my brothers and sisters were taunted as “cat-licks.” Then came the day when several men, clothed in the white cloth of the Klan with their pointed hats and mounted on horses, rode around our house.

During both the cross burning and the ride-around, another neighbor, Jack Mercer, stood by my parent’s side shouting out the names of every rider. He recognized them, hidden behind their sheets, by their horses, their shoes, or their stature. This was, after all, a small community where everyone knew everyone. So instead of being forever laden with fear or hatred, I was gifted with the knowledge of the integrity and courage it takes to stand up in the face of racism, sexism, or other adversity. Jack set a standard for how I have tried to live my own life.

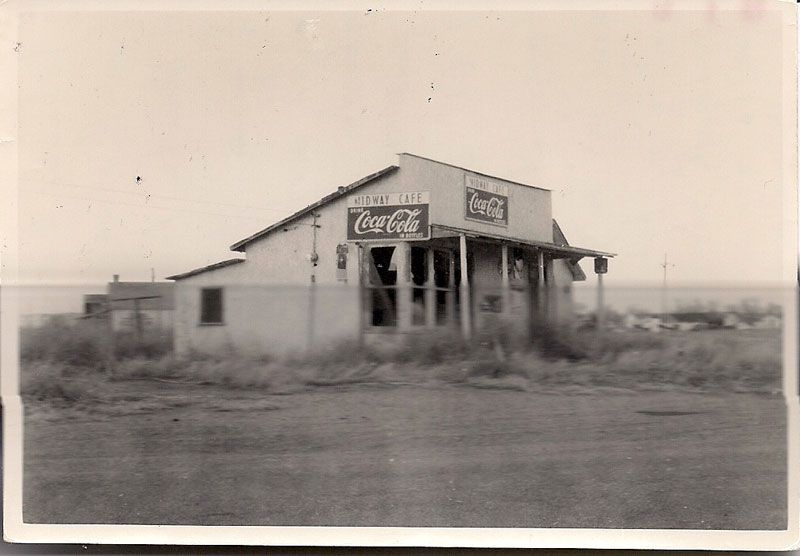

Once the KKK riders left, several of them went to a small coffee shop not six blocks from our house. Mother, so I am told, rolled up an issue of the Scottsbluff Star Herald and marched over to the café (photo 4HA4). She grabbed one of them by the collar, jerked him from his chair, and gave him a few whacks across the face with her rolled up newspaper. Don’t’ mess with a mother guarding her children.

The main tools needed to build a dugout shelter are a shovel, a strong back, and determination. Our childhood friends and their parents couldn’t pay the rent on their wood frame home so they had to move on around 1930. A rancher allowed them to build a dugout on a “worthless” piece of ground about two miles outside our town. They picked out a south facing hillside, bent over, and started digging.

The dirt walls remained dirt walls. How could they be different? The only plaster available was mud made from the excavated dirt. Some times a white sheet would be hung over a wall section to lighten the space a bit. I recall seeing niches dug into their back wall where they could set a kerosene lamp or maybe a prairie flower in a quart jar. Yes, even the poor like flowers.

The windows panes were not real glass. People had devised a way to let in a little light by using what was called “butcher paper.” This paper was white or light tan and came in a large, 2 ft. wide roll. It was used in grocery stores to wrap fresh meat for a customer. To make a window pane, the first step was to cut a window frame size piece from this paper. Then the paper was coated on both sides with tallow, lard rendered from animal fat. This gave some strength and durability to the paper which was then secured to the frame. Not much light entered through these makeshift panes, but as the saying goes: “It was better than nothing.” What’s a poor man to do?

We moved on to another town in 1942, but I still miss my childhood playmates and their sheltering dugout. I miss other things too. I miss the sandstone hills where we played in their quiet valleys full of flowers and wild, sweet tasting berries. Those hills were known to me as only children can know them. They spoke to my heart, bringing me peace, reminding me that I am not a stranger in my own world.

I miss the rolling waves of the tall, prairie grasses, often wild and free. I used to lay back flat among them, protected, feeling the summer breeze blowing over my head, letting the grass stems caress me, leaving me feeling safe and cared for.

In the fall of the year, I loved to watch the leaves fall from the few trees we had in our town. They came from their places on branches to blanket our earth with their gold and reddish colors. They waved like unfurled flags as they drifted toward the ground. They reminded me that I too am tied to a branch that will one day let me go.

Read more of My Story As told By Houses:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Affordable IR Camera

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Handy Heat Gun

View Comments

Larry, You are clearly one of the folks who emerged from those dark times with a generous soul. Or maybe it wasn't quite so dark because people knew they were all in the same boat. Your account is particularly important today because, I fear, blaming other people is a more common response to adversity. So thanks to you for a fine story and thanks to Fine Homebuilding for running it.

A very nice story... the photo however is a poor example of what a dugouts could be. My great-grandfather and his wife moved from Quebec to Nebraska in 1870's; their only option (w/ little wood about) was a dugout on their homestead near Campbell, built with sod-walls. The only lumber was used for door and window frames (I presume local logs supported the ceiling).

My grandmother was born in that shelter, but would never admit to that humble beginning. We have a surviving family photo of the immigrant French-Canadian couple with a baby in arms (grandma) and her 2 older brothers. A horse stands on the creek bank above the house (possibly on the roof).

More children were born there and more still in the wood house that replaced that sod/dugout: 11 in all, 9 survived to adulthood, 8 that lived to beyond 90. Hardy pioneer stock from a humble but healthy heritage.

robinkaren,

I'm glad you and other folks have been sharing similar stories about early American life. Larry described a sod home in one of his earlier posts that seems more like what your family must have built. I added a link to the post at the end of this article (entitled "The Soddy"). I believe he reserved the term "dugout" for the more primitive dwellings he had seen years ago.

What a wonderful story and insight into times past--and yourself. It speaks strongly of basic appreciation of life in and of itself. I could almost smell the prairie grass and feel the warm breezes, and sense the pulse of those times past. Good medicine.