Steve Bluestone, the New York real-estate developer with a special interest in a building material most builders ignore, is about to embark on a self-financed experiment that will test the effectiveness of high-mass walls in a cold climate.

Bluestone last year built a house in Hillsdale, New York, with autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) blocks. The blocks, produced by a single manufacturer in the U.S., are lighter than conventional concrete blocks, and better thermal insulators. A few high-performance builders use them, but most do not. Bluestone thought AAC deserved a try.

Exterior walls of the 4200-sq.-ft. house are built with 8-in.-thick AAC block wrapped on the outside in 4-1/2 in. of rigid polyiso insulation and finished in James Hardie fiber-cement siding. He learned recently the building, described earlier this year in an article at GBA, will be certified by the Passive House Institute U.S. As far as Bluestone knows, it will be the first AAC building in North America to be certified.

The house was expensive enough that Bluestone didn’t want to talk about how much. Now he’s drawn up plans for a woodworking shop on the property that will help him learn more about AAC construction, whether there are less expensive ways to use it, and whether Passive House computer modeling of high-mass walls is accurate.

“I’m still not done figuring out this AAC, and seeing what it can do, and how to do it cheaper, and I thought why not build a shop with AAC and try something without this expensive outboard system of polyiso and cement board.”

Insulating in stages

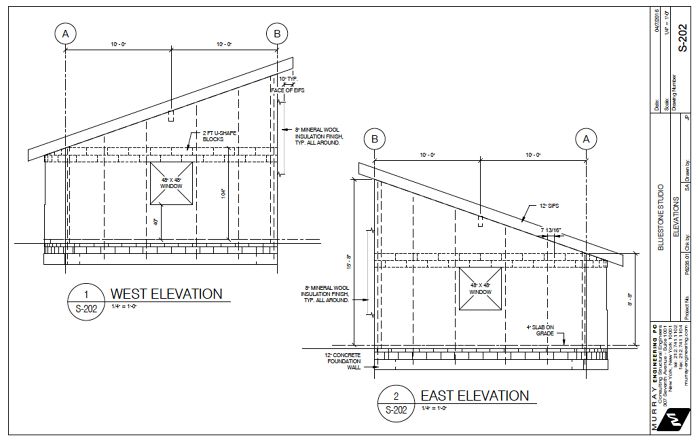

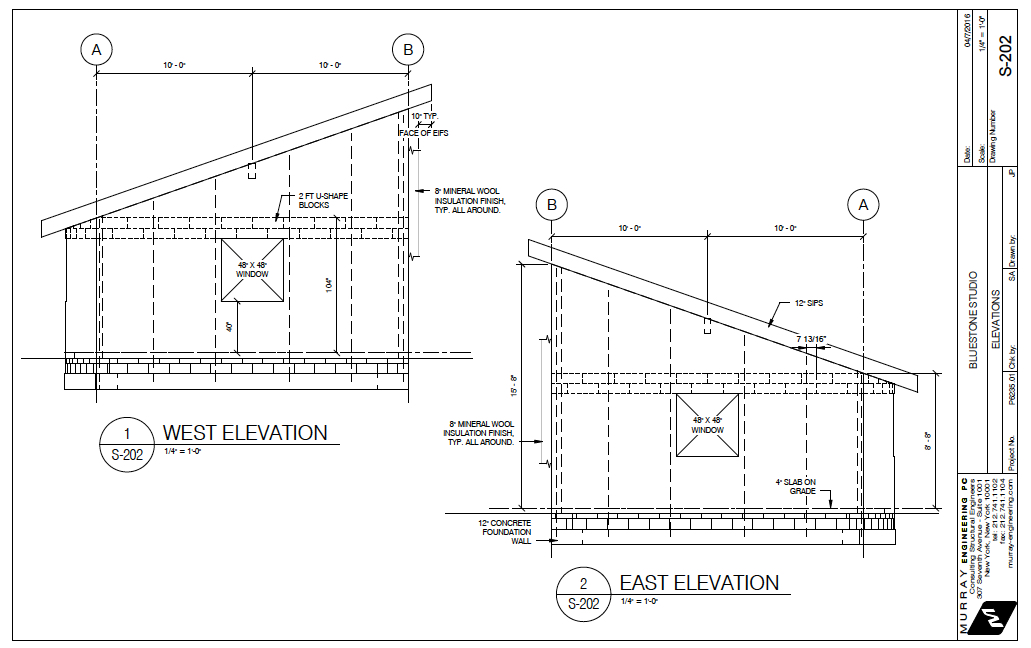

Instead of insulating walls with polyiso, Bluestone plans on using Roxul mineral wool, attaching it directly to the outside of the block and finishing it with stucco. That should lower labor costs. But the exterior insulation won’t go up right away. Bluestone plans on adding it incrementally, taking two or three years to find out just how much exterior insulation is needed before the building meets energy requirements of the PHIUS building standard.

While exterior walls are a variable, the structural insulated panel roof, the windows, and the sub-slab insulation will be designed to meet Passive House requirements from the start. By adding insulation in stages, and measuring energy consumption at each step, Bluestone in effect will be testing the accuracy of computer software designers use to predict energy use in Passive House buildings.

This AAC house under construction on Staten Island, New York, is one of three being built by Bluestone’s real estate development company. (Photo: Leon Davis)

Bluestone explained it this way:

“I’ll put the heat pump in and let it run for a year and see how poorly it did, because it’s only an R-10 with a mass wall. Then, in year two, put some insulation on the outside, incrementally add it, go a second year, a third year, until I get to the Passive House level.

“The Passive House program might say 10 in. of Roxul,” he continued, “but I’ll have this mass wall thing and this unknown of the effect of a mass wall. What happens if I do this every year, and I go in 4-in. increments to zero the first year and here’s my energy bill to heat the place, 68 degrees all year long…Year two, put 4 in. of Roxul on the outside and find a way to shed water temporarily, then monitor for another year. Do the math after the year’s up, go to year three and put another 4 in. of Roxul on.

“Now I have 8 in. of Roxul and 8 in. of block and lo and behold maybe that’s enough,” he said. “I want to see if the program is right by working up to its number and if I reach Passive House consumption on a watts-per-square-foot basis before I actually that much insulation that Passive House said to put on, well, that would be an interesting story.”

Testing lab results

Thick walls made from heavy, dense materials — such as adobe in traditional houses in the southwestern U.S. — soak up heat during the day and release it at night. This keeps people comfortable by protecting them from the sun’s heat during the day, and warming them at night after the sun has gone down. By the time the walls have lost all their heat overnight, the sun is rising to warm them up again.

High-mass walls were a cornerstone of early passive solar design. But in a cold climate, where daytime temperatures never get very high during the winter, the walls get cold and stay cold for months on end. They can be a liability, not an advantage.

The performance of high-mass walls has been studied by building scientists, including researchers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, but Bluestone says there’s a shortage of the kind of empirical evidence his experiment should produce. And it may help deflate some of the claims builders have made over the years.

“There’s a whole bunch of people I deal with in the concrete world and many of them say, ‘Oh, the mass wall. You don’t need any extra insulation on the outside. You just go with the 12-in. block and you’re all done, you can do Passive House,’ ” Bluestone said. “And I say, ‘That sounds great. Have you done it?’ And they go “Hubba-da-hubba-da-hubba.’ ‘” Have they built a house and monitored it? Hubba-da-hubba-da-hubba. So, maybe in theory, but in reality I don’t know.”

Bluestone isn’t selling himself as a building scientist or researcher, and someone will have to interpret the data he collects in his multi-year experiment. For example, it’s not clear how he will account for variations in local weather conditions — a cold winter one year, a warm winter the next — affecting the amount of energy needed to heat the building. Temporary cladding protecting the mineral wool insulation will have different properties than the permanent stucco finish he plans at the end. That, too, could skew results.

But Bluestone hopes the project will add new information to what’s already known about the performance of mass walls and, ultimately, advance the use of AAC.

In an email, he recalled an ongoing correspondence with an architect and author who claims all the data Bluestone wants about AAC already is available.

“We’ve been kind of like a scratched record (or CD disc) that keeps skipping,” Bluestone wrote. “Needless to say, he has never produced proof of what he has claimed. Perhaps all of this is just my way to prove him wrong? Maybe, but deeper down, I’m looking for the simplest, cheapest, longest lasting Passive House envelope system that almost anyone can build.”

Similar project nearby

Bluestone’s wood shop project will borrow a few pages from fellow AAC convert Dan Levy, who is nearly finished working on a house and adjacent garage in Woodstock, N.Y., a town some 50 miles southwest of Hillsdale on the west side of the Hudson River.

Levy’s 2400-sq.-ft. house is made from 8-in.-thick AAC block insulated on the outside with 6 in. of Roxul ComfortBoard IS rather than petrochemical foam insulation. Beneath the footings is a layer of Foamglas insulation, another non-chemical product.

Walls are insulated to R-34, the ceiling to R-88 with blow-in cellulose, and the slab and footings are insulated to R-34. A preliminary blower-door test showed air leakage at 0.5 air changes per hour at a pressure difference of 50 Pascals. Levy says AAC buildings can be much tighter than that and suspects gaps in an ceiling membrane and around plumbing lines could account for his result. He, too, will be looking for PHIUS certification when the house is complete.

Levy is a 64-year-old former professor of industrial education who backed into residential restoration work when jobs in his field dried up. He first used AAC block on an addition to his house in Maryland–just the block and no exterior insulation. He was hooked, and two years ago bought property in Woodstock to build a house there.

In nearby Woodstock, New York, Dan Levy is nearing completion of an AAC house with an adjacent garage. Exterior walls are insulated with Roxul mineral wool. (Photo: Dan Levy)

“I’ve worked on many old buildings and it’s rare to find an older wood-framed building that doesn’t have lots of areas that have rotted,” he said by phone. “And I thought, if this material does everything I’ve read about it would be worth trying. It was much simpler than I expected, and it worked better than I expected. I thought it was a great way of starting a business to teach people how to build a better house.”

He chose Woodstock because he knew people there, and he thought a Woodstock address would have enough cachet to help him sell the house, now on the market with 3 acres of land for $750,000. (You can learn more about the Woodstock Passive House by visiting Levy’s website.)

Acceptance for AAC by builders as well as the public has been a tough sell, Levy said. When he completed the addition in Maryland and could point to the many advantages of the material, Levy didn’t get the reception he thought he might.

“Instead, everyone laughed at me,” he said. “Builders said, ‘Wait a minute. You want us to change our entire model?’ The only people who didn’t laugh were the building inspectors. They came out fully briefed, because I had provided everything in advance, and their only question was, ‘Where did you get it? This is great.’ “

Read more: http://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/green-building-news%2A#ixzz45jYrMBXW

Follow us: @gbadvisor on Twitter | GreenBuildingAdvisor on Facebook

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Reliable Crimp Connectors

8067 All-Weather Flashing Tape

Handy Heat Gun

Steve Bluestone's woodworking shop in upstate New York will help test how effective high-mass walls are in a cold climate. The building will be constructed with autoclaved aerated concrete block.

View Comments

I'd like to clear the air a little about the "cost" issue. We put a lot of very expensive and unique aesthetic design details into the house, some very expensive custom made cabinets, high end appliances, and a fair amount of other bells and whistles that all drove the price up a bit. That, and the fact that much of the construction was done on a time and materials basis (which as most people know is aure fire way to blow any budget out of the water). The way we went about putting on the siding was very laborious, and thus very costly, but it did work like a charm. The AAC blocks only cost about $12 to $13 per SF to buy and install. While that may seem like a lot, stop to think about what that provided. A wall that is vermin/insect proof, an envelope that needed no added materials for air, vapor, fire, or water barriers, no interior furring, structure, and an approximate R-10 with no thermal bridging. When you look at all of these factors, the price for the AAC isn't that high at all. The workshop will hopefully give me an opportunity to bring the cost of the additional insulation and rain screen system down to a very reasonable level. And, the AAC wall will in theory last hundreds of years if not more. Talk about life cycle costing. Try to get all of that with sticks. Steve

I left out one item above in talking about the virtues of AAC. By having it inboard of the exterior insulation, the mass wall effect provides for an extreme level of comfort. With our thermostats set at just 63 - 64 degrees inside all winter, it was very, very comfortable wherever you were (in the sun, out of it, near a window, away from it, etc., etc.).

Unless you have spent some time in such an environment, all of this is just words. It really is hard to describe.

Can we see the interiors? I got quite curious after your comment.

Nathan (and others), I'm not as computer literate as I'd like to be, and am not quite sure how to post photos into this log. If you would like to see some photos, please email me directly ([email protected]) and I'll send you a few directly in my response. Sorry about this!