When Sunshine Drives Moisture Into Walls

Energy Nerd: How inward solar vapor drive happens, and avoiding the problems it creates.

The unseen threat

Builders first started worrying about vapor diffusion in 1938, when Tyler Stewart Rogers published an influential article on condensation in the Architectural Record. The article, “Preventing Condensation in Insulated Structures,” states, “A vapor barrier undoubtedly should be employed on the warm side of any insulation as the first step in minimizing condensation.” Rogers assumed that the main source of condensation on sheathing was the result of the diffusion of water vapor through the wall and ceiling plaster in wintertime.

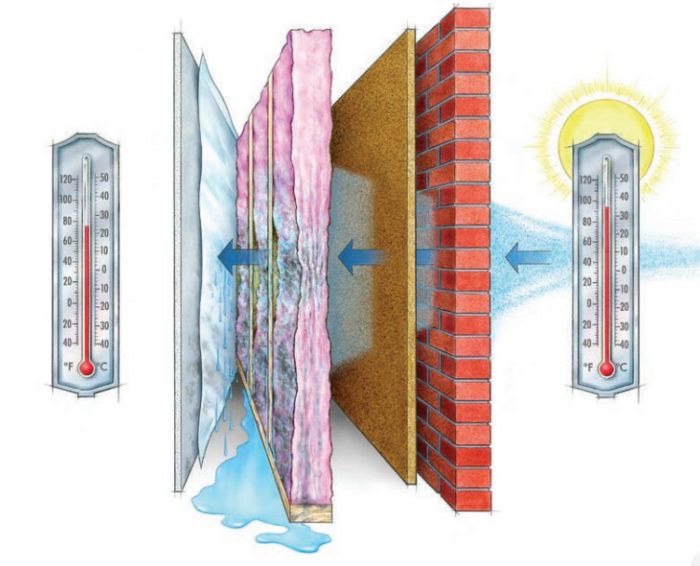

Rogers’ recommendation to use interior vapor barriers, which was eventually incorporated into most model building codes, became established dogma for over 40 years. But eventually, building scientists discovered that interior vapor barriers were causing more problems than they were solving. Interior vapor barriers are rarely necessary, since wintertime vapor diffusion doesn’t typically lead to problems in walls or ceilings. What Rogers didn’t know back in 1938 is that the main way that sheathing gets damp in the winter is actually via air leakage, not vapor diffusion. But a different phenomenon — summertime vapor diffusion — has become the far more serious matter.

Zaring Homes goes bankrupt

During the 1990s, summertime vapor diffusion began to wreak havoc on hundreds of North American homes. This epidemic of rotting walls was brought on by a combination of two factors that Rogers did not predict: The widespread adoption of air conditioning, and the use of interior polyethylene vapor barriers.

Rogers had conceived of interior vapor barriers as a defense against the diffusion of water vapor from the interior of a home into cold wall cavities. But he couldn’t foresee that these vapor barriers would eventually be cooled by air conditioning, thereby turning them into condensing surfaces that would drip water into walls during the summer.

Interior vapor barriers—such as polyethylene under the drywall or vinyl wallpaper over it—are unforgiving. They not only prevent outward diffusion during the winter; but also inward drying during the summer. These days, building scientists instead recommend the use of vapor retarders like MemBrain, kraft paper, or vapor-retarder paint.

It took a series of disasters to fully illuminate the phenomenon of summertime vapor diffusion. One early victim was Cincinnati builder Zaring Homes. In the mid-1990s, Zaring Homes was a thriving midsize builder that completed over 1,500 new homes a year. But the company’s expansion plans came to a screeching halt when dozens of its new homes developed mold and extensive rot.

The first signs of a problem surfaced in July 1999, when homeowners at Zaring’s Parkside development in Mason, Ohio, began complaining of wet carpets only 10 weeks after the first residents moved into the new neighbourhood. When inspection holes were cut into the drywall, workers discovered 1⁄4 in. of standing water in the bottom of the stud cavities. “We were able to wring water out of the fiberglass insulation,” said Stephen Vamosi, a consulting architect at Intertech Design in Cincinnati.

Consultants concluded that water vapor was being driven inward from the damp brick veneer through permeable Celotex fiberboard wall sheathing. During the summer months, when the homes at Parkside were all air conditioned, moisture was condensing on the back of the polyethylene sheeting installed behind the drywall.

“Zaring Homes went out of business because they had a $20 million to $50 million liability,” said building scientist Joseph Lstiburek. “Hundreds of homes were potentially involved. To fix the problems would probably cost $60,000 to $70,000 per home. It was a spectacular failure.”

For diagrams and information on how inward solar vapor drive happens, click the View PDF button below.