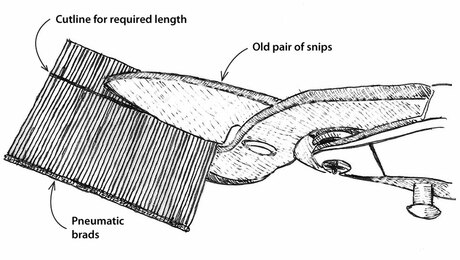

Synopsis: A finish carpenter discusses the use of two pieces of material to make crown molding up to 12 in. wide. He shows backing blocks at the ceiling that support the molding, and shows how to cut the molding on a chop saw.

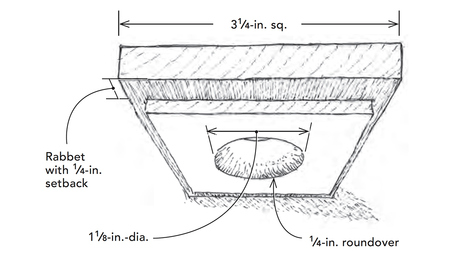

I work as a finish carpenter on the San Francisco Peninsula, where there is a resurgent interest in formal houses that have a Renaissance European flavor. The houses often have a full complement of related molding profiles for base, casings and crown, and to be in scale with the rest of the building, these profiles can be quite wide. In the case of the crowns, I’m talking 10 in. to 12 in. wide. In fact, the crown moldings that I sometimes install are so wide they come in two pieces.

There are several reasons crown in two sections. First, the machines that cut the moldings typically have an 8-in. maximum capacity. There is a lot of waste when wide moldings are carved out of a single piece of stock. For example, I’d need a 3×12 to mill a 10-in. wide piece of crown — an expensive, inefficient use of the resource. Two-piece crowns are also a little more forgiving during installation. The type I used on the job in this article can be overlapped in and out a bit, allowing the width of the crown to grow and shrink as needed to account for dips and wows in the walls and ceilings.

All the two-piece crown moldings I’ve encountered have been custom-made. The designer or architect comes up with section drawings; then the mill shop has the molding-cutter knives cut accordingly. Here, an average set of custom knives costs $35 per in., plus there is a $75 setup charge for each profile. So before the wood starts to pass over the cutters you’ve already spent a fair amount of money. But to create a certain look, it can be money well spent.

Stain-grade or paint-grade trim

If you’ve got one, your architect or designer will decide what grade the trim should be. If you don’t, your checkbook will decide. At the mill, stain-grade means the stock is clear and virtually free of knots. On the wall, stain-grade means no opaque finishes will be applied. The moldings are individually scribe-fitted, and that means no caulks or putties to fill any gaps that may occur at miters and along uneven walls. Paint-grade material, on the other hand, will have some sapwood and uneven grain. On the wall, it can have caulkable gaps. Obviously, the stain-grade material will cost more — how much more depends on the species of wood. And it costs a lot more to install. Where I work, we figure four to five times more labor is needed to put up stain-grade crown as opposed to paint-grade.

The most commonly used paint-grade materials in these parts are alder, poplar and pine. I see more poplar than anything else because it’s relatively inexpensive and easy to mill. Even paint-grade moldings, however, don’t come cheap, and they should be handled with care. I have them primed on both sides as soon as they are delivered, and I store them on racks with supports no farther apart than 3 ft.

For more photos and details, click the View PDF button below: