Designing Forms for Tall Concrete Walls

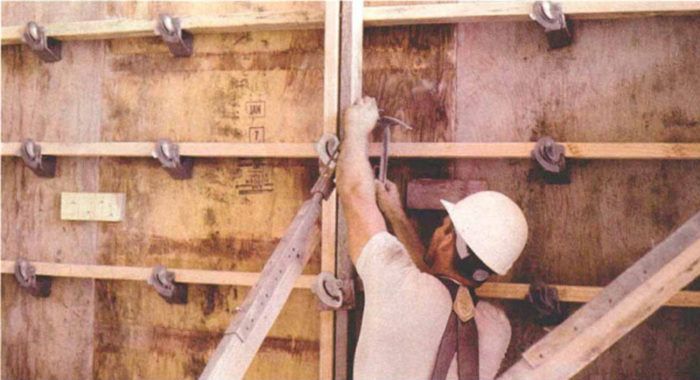

Site-built panels that hold up under the stress of concrete.

Stop the pour!” The words echoed through the basement, loud enough to be heard over the transit-mix truck’s engine and the grinding pulse of the pumper.

“I’ve heard that before,” said the driver to nobody in particular. “That’s the cry of panic.”

The problem started when a snap tie snapped at the wrong time. My friend Charles, a builder who specializes in remodeling, was used to building his forms with plywood and snap ties. He’d never had a problem with the system and didn’t bother sizing the ties or spacing them to suit different circumstances. He used what he had on hand, and it always held together.

But this time the concrete dispatcher did him a favor by sending three truckloads of concrete in quick succession (he wanted to make up for a year’s worth of late deliveries, and it was a slow day at the yard). Filled quickly to their tops, the forms strained against the weight of the soupy concrete. One of the ties popped, and the forms bulged outward. The adjacent ties, already at their limit and now having to pick up the load of the failed tie began to pop in quick succession. In the blink of an eye, the form unzipped, engulfing the laundry room, the water heater and the new furnace in 20 yards of fresh concrete.

Why did the forms fail? Was a tie left out? Were they too far apart? Or was the wall poured too fast? Would stronger ties have made a difference?

In my experience, most carpenters have good instincts when it comes to working with concrete. They know how to build forms and how to brace them against the imposing loads brought to bear by truckloads of fresh transit mix. But I don’t know many carpenters who understand the criteria that govern form designs. Few carpenters know what the proper pour rate is or how to proportion the forms to achieve economy in material. Most carpenters overbuild the forms and hope that they’ll hang together. Using a form that is significantly overdesigned is almost as bad as pushing an underdesigned form to failure. Both practices waste money, and in the case of failure, somebody might get hurt.

I work for a large general engineering firm in Los Angeles, California, and along with several other engineers, spend a portion of my time designing site-built concrete forms, some of which are very complex. But you don’t have to be an engineer to size the forms for straightforward pours—even the 8 ft. to l0 ft. walls that are typically cast for basements or retaining walls. What is necessary is an understanding of what a form should do, what forces are going to be acting on it, what materials are available for building the form and the limitations of those materials. Once you’ve got a handle on those variables, you can use the table below in the PDF to design your own forms.

For more information on how to design forms for concrete walls, click the View button below