The Argument for I-Joists

New products and increased competition make superior I-joist performance available at solid-lumber prices.

Synopsis: Written by a building scientist, this article explores the benefits of building with I-joists, an engineered alternative to solid sawn lumber. Includes an overview of how I-joists work and how they are best used, as well as a chart comparing the cost of using I-joists vs. solid lumber to frame the floor of a typical 28-ft. by 44-ft. ranch house.

Although Apollo 11 and Woodstock got all the attention, 1969 was also the year Trus Joist Corporation (now Trus Joist MacMillan) unveiled the first wood I-beam. The development of the I-joist was originally driven by performance, not price. High-end contemporary designs were inspired by homeowners who wanted open floor plans, which required long clear spans. I-joists, with their deep plywood webs edged by lumber flanges, were much stronger and stiffer than sawn joists, and they gave designers the free hand they needed to fashion less restrictive loadbearing strategies.

While I-joists offer many advantages over sawn lumber, unfamiliarity and high prices have kept most builders from trying them. But the truth is that I-joist installation is not that different from solid lumber. And the really good news is that the prices of I-joists are dropping. The timber crisis of the 1990s has made prices of engineered-wood products, such as I-joists, more stable than lumber. There is also a growing number of new, small companies that are fighting hard for market share; many of these companies have fine products at competitive prices.

I-joists don’t waste fiber where it’s not needed

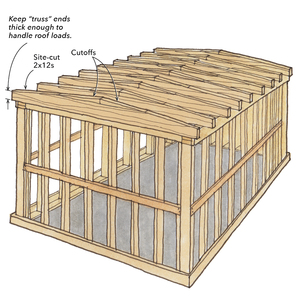

To understand how an I-joist works, imagine what happens when weight is placed in the center of the floor. As the joist deflects and bends — essentially forming an arc — the wood fibers along the top edge are compressed, while those along the bottom edge are stretched. Because the edges are moving in different directions, at some point the wood fibers in between are neither compressed nor pulled apart. I-joist designers take advantage of this fact by placing the strongest and stiffest fiber in the flanges where the stress is greatest. But they don’t waste fiber in the center where it’s not needed. This fact is why I-joists can get away with a web that’s only 3⁄8 in. thick.

To understand further why I-joists are so efficient, it’s important to understand the properties of solid lumber. Double the thickness of a joist, and it will carry twice the load; double the depth of a joist, and it will carry four times the load. Likewise with stiffness: Double the thickness of a joist, and the deflection is cut in half; double the depth of a joist, and the deflection is reduced to one-eighth. Adding depth to a joist increases strength, stiffness and potential clear span. With an I-joist, a minimal amount of wood fiber is all it takes to increase the depth.

One I-joist can do the work of two or more solid joists

Solid-lumber joists are typically available in maximum lengths of 16 ft., and they’re usually laid out 16 in. o. c. To span the average house, separate joists are installed across the front and the back, and lapped over a girder beam at midspan.

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Sledge Hammer

Short Blade Chisel

Portable Wall Jack