“I want to do with you what the spring does to the cherry tree.”

–Pablo Neruda

Does anyone still remember the Korean War? Or is it just another forgotten war that happened elsewhere some 60 years ago? Even a causal reading of history shows that the list of our forgotten wars is long, long. To my surprise, this deadly war opened me somewhat like a cherry blossom.

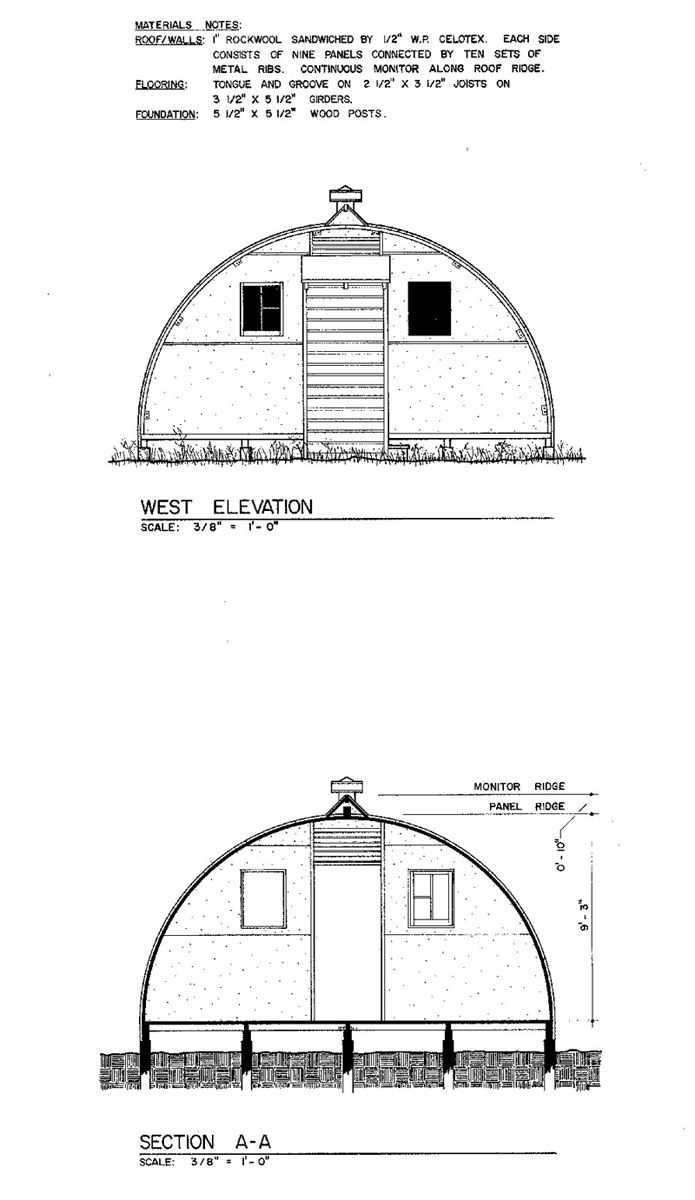

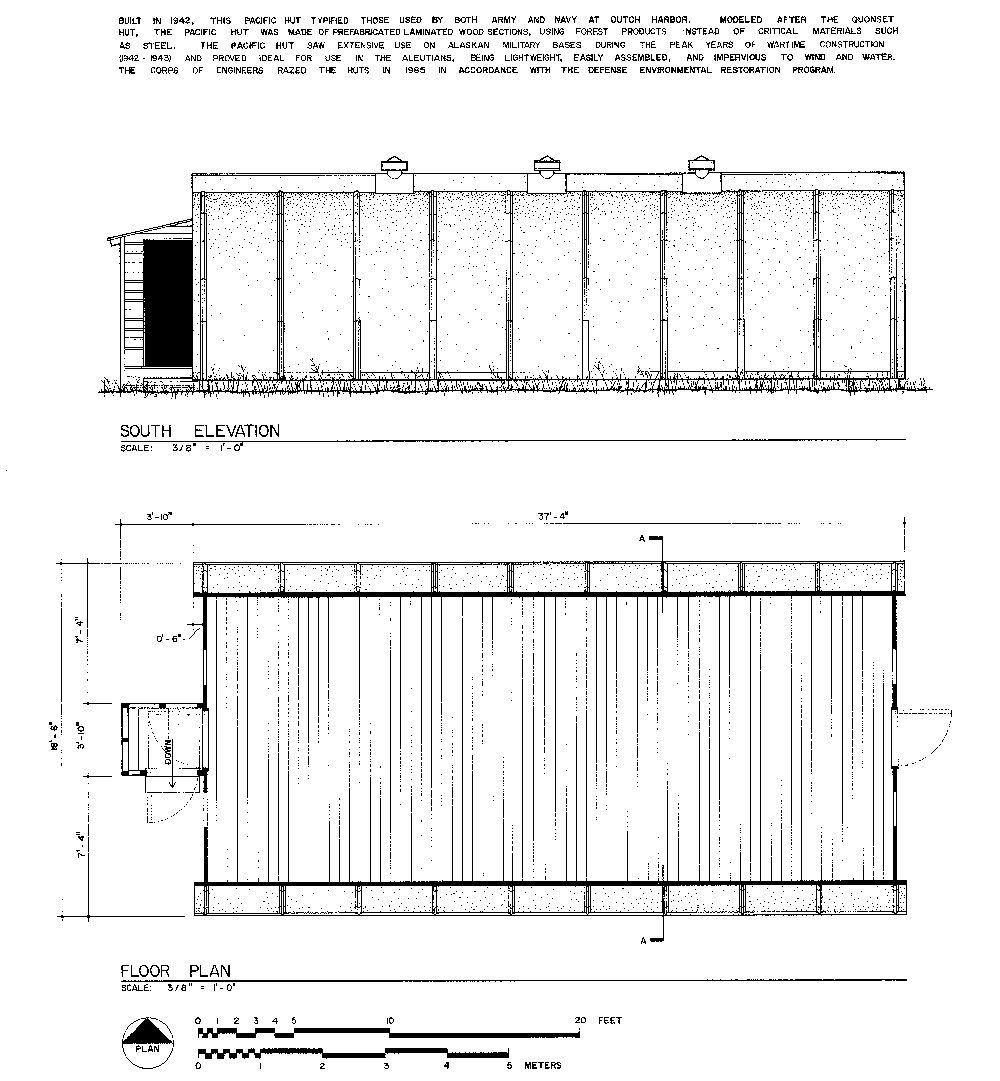

The Quonset hut was born in one of our many wars. In many ways this hut is an icon of WWII especially in the Pacific war theater. Yes, that’s what they call it–theater. The problem of housing the huge number of military personal along with storing materials needed to wage a massive war was vast. Inventive minds quickly found a solution and started producing this oval, metal building near Quonset, Rhode Island, from whence comes its name.

Sometimes we get things right and build like nature does. There is a natural way of being that seems to be unknown or simply ignored by us. We build our houses in straight and square lines. Where do we see this in nature? The Quonset hut is an exception. This strong, stable, half-round structure is shaped like a clam shell, the long-house of the Iroquois People, or the curved home a turtle carries around on its back.

The Korean War that left at least 35,000 young, vital Americans dead, began in June, 1950, when I was of prime draft age, and lasted until July 1953. At the time, I wanted to continue my studies at UCLA. I was also working and didn’t want to go fight in any war any where. I admit to being shy of all wars. I remember what Gandhi once said: “I know many causes I would die for. I know none I would kill for.” Some of us feel that way. I know the death and destruction wars cause not only to our physical well being, but also to our mental health.

I knew I was going to be drafted. No student deferments were offered like during the Vietnam War. Having seen what trench warfare had done to my own father and many others, I really didn’t want to go.

The fringe benefits of being a carpenter. A friend helped me to find a solution of sorts. I was a journeyman carpenter so I joined a reserve unit of Navy Seabees, a construction battalion. It wasn’t long after that, in Oct. 1951, that I was called up for two years of active duty. I was sent to boot camp at the large naval base in San Diego and trained in the art of war.

From San Diego, I went to Port Hueneme, north of Los Angeles, for further training in construction. It was at this base that I encountered rows of the versatile Quonset hut set up for hundreds of different uses. I lived there in a hut for three months. This base is a training and staging area for military construction workers being prepared to build and fight in a war zone. I was there with a battalion of young men, more than seven hundred of us, all scheduled to be sent to Korea.

Maybe someone can help me understand what came next. It happened near the end of our training. We were preparing our gear to ship out to the Korean Peninsula when I was approached by an officer I had never seen and did not know. He came up to me with one question: “Do you want to go to Korea?” I answered—well, no, not really. He turned and left. I and one other recruit from Indiana, received orders to report to the Seabee base in Quonset Point, Rhode Island! Everyone else was headed for the war zone. I’m serious, what was going on here?

Quonset Point, the home of the Quonset hut. There I was placed in another battalion and we were soon on our way to Newfoundland, an island province off the coast of eastern Canada, to build landing strips and a new base post office.

The six months in Newfoundland passed quickly and we returned to Rhode Island. Again it happened. Shortly before we were ready to leave for Cuba, another officer came to me. He said that there was a special group that had been undergoing survival training in Canada and were preparing to leave shortly for an experimental task on the Greenland icecap. The carpenter who was part of this small group had an appendectomy and wouldn’t be going on this expedition. Would I be willing to take his place?

The fringe benefits of growing up in Nebraska: Maybe he asked me because my records showed that I came from western Nebraska where winters can be almost as bad as those in Greenland. I said yes. The nine member group I joined had three mechanics, an electrician, a cook, two equipment operators, an officer, and me the carpenter. It was called the US Navy Seabee Hardtop Detachment and left for Greenland around Christmas time, 1952. Greenland is the world’s largest island about three times the size of Texas. The Greenlanders have home rule, but the island is still owned by Denmark and is mainly covered by a thick, now rapidly melting, ice sheet.

We arrived at Thule air force base located on the west coast of Greenland about half way between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole. We stayed at the airbase for a time, preparing to set up our camp about thirty miles out on the icecap. Our project was to see if the nine of us could use heavy equipment to build an airstrip on the ice that would support the landing of wheeled aircraft.

Four of us were transported out to our station on the ice cap. Besides us, the plane carried basic supplies, two tents, small stoves, fuel, food, and bedding to begin camp setup. We landed, looked around, unloaded our gear, and began to set up our tents. We cut blocks of ice-snow to form a wind barricade and a place for our toilet, had some food and crawled into our sleeping bags.

The two Jamesway huts, each 16 ft. x 16 ft., came in 1,200 pound packages. We opened the boxes and set them on the 2×12 foundation bolting them together to make the floor. The ribs were made from wood and joined together to form an arch. Each arch was attached at each end to the floor by a bolt. Each arch was attached to the next one by a spacer that hooked the two together. Once we had all the arches in place, we began covering them with the insulated blankets that measured 4 ft. wide. These blankets attached to the ribs, to each other, and to the floor to keep them in place. The ends of the hut were also covered with insulated blankets that had a vent for air circulation and an entry door. We had practiced putting them together back at the airbase so even though we were working in -0 degree weather, we had the first hut in place in less than three hours. When you are in the middle of Greenland, you may not have the luxury of building slow.

In less than a week we had the two huts in place along with stoves for heating, cooking, and melting ice to use as drinking water. Our two small stoves, burning diesel fuel, made me realize how little it takes to pollute our environment. Within a short time, the endless snow and ice around our living space was coated with black soot. It helped me to understand the impact a million gas burning cars and hundreds of coal fired plants generating electricity has on the quality of air we breathe in our cities and throughout our country. City folk must have lungs the color of the blackened snow.

Rounded buildings work much better in this cold, windy climate than those with a flat side like a regular house. The wind blows up and over their tops. Once all our buildings were complete we were quite warm and cozy. It wasn’t long before our home was further insulated by snow and ice particles that drifted over the huts.

We staked out an airstrip less than a mile away and began work. We organized ourselves, working 4 hours on and 4 hours off, keeping at the airstrip building task 24 hours a day, seven days a week. We seldom shut the engines off on our two small caterpillars. We used the Cats to pull an ice pulverizing machine up and down the landing strip breaking the ice into smaller and smaller particles and then compacting all with a heavy roller. Hard work, but at least I wasn’t expected to kill Koreans. For that I am forever grateful.

[[[PAGE]]]

We had instruments to test the depth and degree of hardness of the airstrip to see if it would support a wheel landing of a C-47. Once the desired hardness was reached, we radioed the pilot at Thule airbase to give it a try. He arrived in an unloaded plane and safely landed, took off, and landed again on wheels rather than skis without incident. I guess we, like our former president, could say: “Mission accomplished.”

My time spent in on the ice cap was beneficial. I learned a lot about myself, blooming like a cherry tree in the far north. We pushed ourselves to the limit working on the airstrip. This calls for more than physical strength. It calls for discipline and mental toughness with little time to think about girls. I found what it was like to live in close quarters with a group of men with different personalities. We couldn’t escape so we had to learn to live with each other’s way of being. It was a happy time for me in lots of ways. They even baked a cake to celebrate my 22nd birthday. This reinforced my experience that happiness doesn’t come from things, but from how we feel about ourselves inside and from our relationship with others.

The dangers that we met in that frozen part of the world helped me to see that we are part of nature not its master. Life there was one of survival unencumbered by a truckload of things that clutter our lives and keep us from being who we really are. And who are we really? I remember what an woman told me once: “I am just an old woman trying to live simply and be loving toward myself and others.”

All paths, in the end, lead to the same graveyard. Living in the far north taught me to follow a path that allowed me to wake up, be present and in touch with my heart. Please tell me, what else is there in life?

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Handy Heat Gun

Affordable IR Camera

View Comments

Great stuff, Larry

Thanks