“Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

–James Baldwin

A chalkline is a tool somewhat like a fishing reel. It has a string in a closed box full of chalk that can be reeled in and out. Reeled out, it is loaded with colored chalk and used to mark lines on wood. Reeled in, the line is reloaded with chalk. The first chalkline I used when I came to California in 1950 was a cotton string wrapped around a stick. To load this line, I pulled it several times through a solid piece of blue colored chalk shaped like half of a lemon. Full of chalk, it was held by one person on each end and snapped to leave a line on the floor.

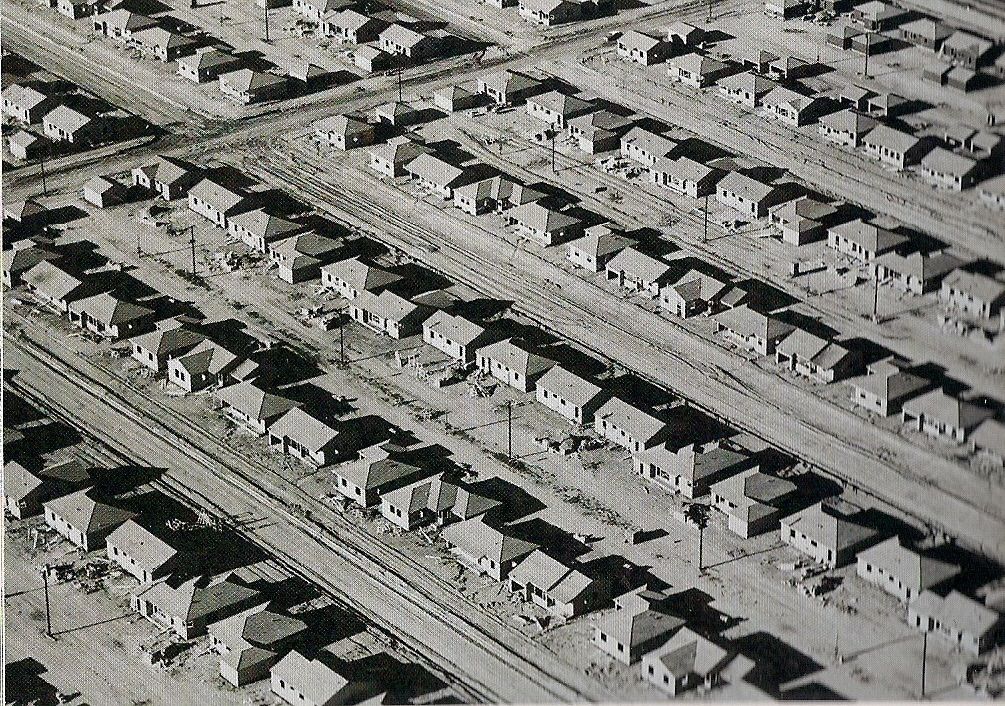

New tools for a new era in America — The chalkline, along with the traditional white carpenter’s overalls, the 16-oz. curved-claw hammer, and the handsaw, typify why we needed radical changes in carpentry after World War II. The old ways were good for their time, but not for what was happening across our country after the war. With the end of the “Good War,” thousands upon thousands of returning veterans, both men and women, with their GI bill and federal loans needed a place to live. Big changes were coming in the construction industry.

But is not change really all there is? Is this not what all life is about? There is a story I heard about a man who kept a small fish in a bowl in the living room, feeding and caring for it. One day the bowl, along with the water, was cloudy and dirty, so he decided to clean it. He placed his little fish in a big bathtub full of water while he cleaned the small bowl. Once he was finished, he went to the tub to retrieve his fish. Lo and behold, he found his fish swimming in a small circle the size of its bowl in this big tub full of water.

The change that had to happen in the construction industry was not cosmetic, and it wasn’t easy for most everyone involved to accept it. Builders and carpenters had seen little change in methods, tools, and materials for 100 years. Houses were custom-built one at a time by a general contractor who supplied both labor and materials and whose workers did everything from pouring the foundation, to building the entire house, to fabricating the cabinets, doing the finish work, installing the door locks, and handing the key to the new owner. A new house often took months or even a year to build from start to finish.

In 1953, my older brother, Jim, got a contractor’s license. My younger brother, Joe, was home from the Korean War, so we decided to start a business. A carpenter’s wage was around $2 an hour, or $16 a day. We found a developer in the valley who was willing to let us do just the house framing for a flat fee. We became piece workers being paid by work done and not by the hour. Framing a small, 900-sq.-ft. two-bedroom, one-bath house built on a concrete slab earned us $90. A three-bedroom, 1,100-sq.-ft. version went for $120. Framing included setting door jambs and window frames, putting on some redwood siding in the front, and making all ready for roofing and plaster. In a short time, we were framing one of these houses complete every day, making much more than the daily wage.

Our free enterprise wasn’t always popular with the carpenters union. The fact that we were just labor contractors was resisted mightily by many older carpenters and by the carpenters union, who feared this would mean less work for its members and affect their paychecks. I recall a union business agent visiting our job site in 1954. He asked to see my long-handled, 22-oz. hammer. He walked to a saw and cut off several inches of the handle so that it would comply with union rules. I went home that evening and put on an even longer handle. Brother Jim was ordered to appear several times in front of union governing boards to justify what we were doing. There is an old saying that let’s you know how it all panned out: “You can cut the flowers, but you can’t hold back the spring.” The revolution in construction was on.

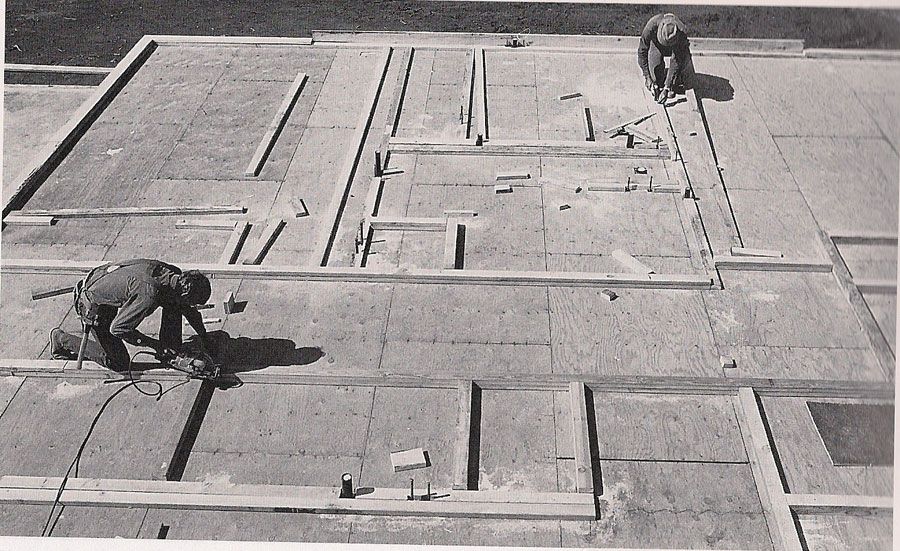

Production framing really isn’t a matter of working harder and faster. It mainly has to do with saving a few minutes here and there by changing tools and methods. Carpenters have traditionally been taught to “measure twice, cut once” to ensure that material is cut to the proper length. I learned that frequently I didn’t need to measure at all. It takes time to use a measuring tape. Often you can cut an exact length by “eyeballing” the length you need. A good example is when you are cutting 2×4 or 2×6 wall plates, the horizontal parts of a wall, to length on a floor. The chalklines are all in place for plate location. All you have to do is lay the 2x plate in place and cut to the chalkline.

Production framing is based on a few simple principles. One important one is: Don’t sacrifice quality for quantity. I have heard people say, “We don’t build them like we used to.” That’s true. After tearing down and remodeling many older buildings, my observation is that we build houses better than we used to.

We were not building gingerbread houses, McMansions, or starter castles. We were building solid, one- and two-story tract houses that working-class families could afford to buy. For the first and probably the last time in our nation’s history, masses of ordinary workers could afford to buy and actually own a home; it was the American dream fulfilled.

One change in our way of working that increased how rapidly we could build houses was a simple one. When I started framing houses in LA, we would snap a chalkline for one wall, lay down and floor plates, cut studs, and build that wall upright, standing in place. Then we would snap a line for another wall, build that, and so on until all the walls were upright. We switched back forth between tasks. The simple change was to complete all of whatever job we were doing before going on to the next one. So when we started building a house, we would lay out room dimensions and snap all the chalklines to mark the location of every wall on the floor. Then we would come back and lay down all of the plates, both top and bottom, on the lines before marking where the studs and door and window headers would be. This went on until every wall for every room was ready to frame. Framing was done flat on the floor rather than upright.

However you build, I encourage you to find joy in what you are doing. Work that is a joy is no longer work. I lived in South America for a time. People in Chile have a saying that I used to hear now and then: “Ustedes, Norte Americanos, saben como existir. Nosotros, Chilenos, sabemos como vivir.” You who live in North America know how to exist. We Chileans know how to live!

Could be some truth in that statement, no?

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Handy Heat Gun

Affordable IR Camera

Reliable Crimp Connectors

View Comments

Larry, I have enjoyed your articles since I started reading Fine Homebuilding about 15 years ago. I did not have any formal apprenticeship and feel that my subscription, and your articles and books, taught me most of what I know about carpentry. Your blog is great and your perspective on building over the last century is very insightful. I look forward to your next post.

Kevin McDermott

My apprenticeship was with my Uncle during summer vacation in the late seventies and early eighties. He was old school though and though. Cursed hard, drank hard and worked even harder. After WW2 he came home and started his own Carpentry Co. At that time the suburbs of New York city was more farm land then suburbs. But, thanks to a bunch of developers,soon tract housing went up real fast. My uncle had built many of the homes. He would tell me stories during lunch time of all the going ons of this new style of building. The cool thing is that now, I am renovating these same homes that my uncle built 50 plus years ago. Add about three or four times I came across his name penciled on a 2x during renovation. My uncle has passed, but I will always look up to him but never measure up to him.

Thanks for the article. It makes my Dads old tools come alive in my hands.