Don’t Forget the Flashing

Easily overlooked and sometimes installed incorrectly, flashing keeps water out and rot at bay.

Few building components are more important to the longevity and structural integrity of a house than flashing. When we look at a building we may see siding, roofing, and windows first, but it is the all-but-hidden flashing that protects those assemblies from water intrusion and the rot and decay that go with it.

Flashing is a waterproof material that diverts bulk water away from areas where it might do some damage. Traditionally, flashing was made from metal, like copper, galvanized steel, lead, or aluminum — materials that are resilient, durable, and flexible or at least bendable and somewhat malleable.

But other materials might also be used, as long as they meet those basic requirements. Modern peel-and-stick membranes, for example, that are used to protect window openings are a form of flashing. So are the rubber-like boots that slide down over plumbing stacks in the roof. (Some years ago, an 18th century house in Maine was found to have birch-bark flashing at the junction of a roof and sidewall; it was still intact and serviceable even though it had been covered up by more recent materials.)

Flashing is almost always installed at the boundary between two adjoining surfaces — at the edge of a roof, over window and door openings, where a chimney emerges from a roof. Flashing carries water from one impenetrable surface to another, and as such is part of an assembly that keeps water out.

Why flashing is more important now

Back in the day of building envelopes that were far from airtight, and with minimal insulation, a small water leak here and there wasn’t the end of the world.

More stringent building codes now call for much lower air leakage rates and a lot more insulation. Houses built to standards like Passive House often have very thick walls, and very few air leaks. Managing water becomes much more important because when wall and roof cavities get wet they are very slow to dry out.

In high-performance houses, moisture management depends on an integrated system of materials. Correctly installed flashing is an important part of it.

The one rule to remember

Flashing details are not always simple and are easy to screw up, but one rule always applies: Think like a drop of water and you should get it right. That is, water must be directed outward, away from the building, as it makes its way down the building. Each layer should be installed over the one beneath it so that a drop of water has no other place to go than out.

If this seems too obvious to even mention, think of the number of deck specialists alone who are called in to repair the damage to siding, sheathing and framing because someone forgot to flash the top of the deck ledger. Oops.

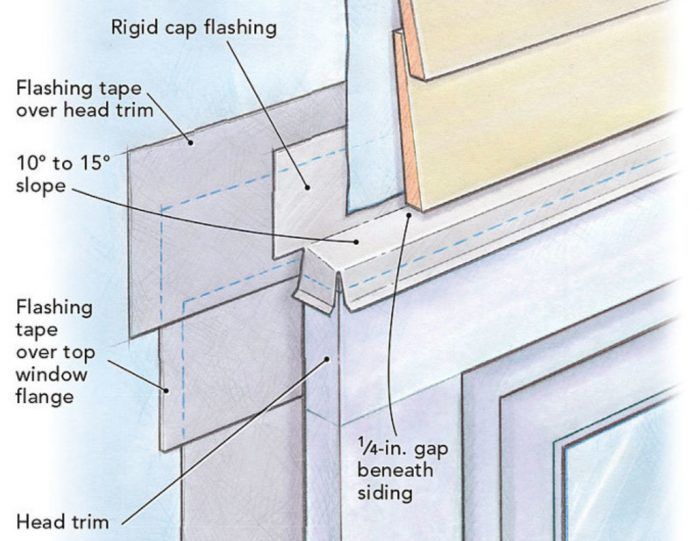

It can get complicated when there are many layers of flashing involved, such as when installing a window. First the sill pan needs flashing, then comes flashing at the jambs that overlaps the flashing at the sill. After the window has been placed in the opening there is the head flashing followed by the overlapping water-resistive barrier (often housewrap). Many layers, but each is installed so it overlaps the previous one: Water goes out.

For a good guide on window flashing, try this video by Mike Guertin or this article by Rob Moody.

Specialized flashing details

Many flashing details will be obvious — such as the step flashing that protects a sidewall where it intersects a roof. Sometimes, however, the need for a special piece of flashing may not be so clear.

Such is the case with what’s called “kickout flashing.” This is a piece of flashing installed at the lower corner of a roof where it dies into a sidewall. The flashing should be bent in such a way that water running down the roof can’t run directly onto the adjacent wall. Instead, the water is kicked out and away from the building. Without this essential detail, water can run right onto the wall. In time, this often leads to decay. (For more, take a look at this explanation in Hammer & Hand’s Best Practices Manual.)

Masonry chimneys are another area requiring special attention. There are at least two layers of flashing here. First comes the step flashing that keeps water out of the seam between the chimney and the plane of the roof. Then comes the counter-flashing that keeps water from running behind the step flashing. The lower corners of the chimney may need a special piece of flashing that makes the turn without a break. This article has more details about flashing details on a chimney.

Caulk is not flashing and other footnotes

It’s not uncommon to see roofing tar take the place of proven flashing details on a chimney. Maybe the roofer was in a hurry, or didn’t know how to repair or replace the flashing. But roofing tar won’t last as long as real flashing, and eventually it will dry out, crack and leak.

The same is true with caulk. Even the best caulk is not as good as overlapping layers of metal or even plastic flashing that has been installed correctly. Eventually, it’s likely to leak.

As great as peel-and-stick products have proved to be, they do not constitute a miracle or an end to common sense. They rely on an adhesive bond that must not fail in order to be effective. Also, they can be difficult to apply in cold weather, and they may not work very well when applied to wet surfaces. Proceed accordingly.

Finally, even metal flashing materials have an Achilles heel: galvanic corrosion. This occurs when two dissimilar metals are placed together in the presence of water. Galvanized roofing nails used to attach aluminum flashing, for example, can lead to premature failure of the aluminum.

If you’re not familiar flashing details, seek out the guidance you need. Your house will thank you for it.

View Comments

It always amazed me how few builders understood flashing in the 30 years I worked on houses. Most of the time it wasn't even used, but often enough it was only a gesture that offered no long term protection. In my work I finally got a metal brake so I could custom make flashing for the inevitable situations where no combination of pre-made flashing could work. This article is great, though it could go into much more detail. At least it may save some repairs, which are often far more costly then simple flashing.