Methods of Alternative Construction

In recent IRC editions, some more obscure materials, such as straw-bale and light straw-clay, and methods were added.

The conventional building methods and materials that have dominated residential building codes in the United States for most of our lifetimes and the prescriptive requirements that guide their use didn’t just drop out of the sky; they were developed over time through trial and error. That these materials and methods came to take center stage isn’t because they were the first on the scene or even the best available; they simply happened to dominate the U.S. building market at the time the codes were written.

Since the formation of the International Code Council and the introduction of the International Residential Code (IRC) at the turn of the 21st century, prescriptive design provisions have expanded to offer a wider variety of choices than existed before in model codes. In wood-frame construction, for example, there are now 16 different methods and materials for braced walls provided in Table 602.10.4—double what was provided in the first edition of the IRC in 2000. Concrete walls using insulating concrete forms (ICFs) have been recognized since the 2000 IRC, and structural insulated panel (SIP) walls were provided prescriptive methods in the 2009 edition, relieving some basic wall designs of individual engineering. (SIP roofs are a different story.)

To regular Fine Homebuilding readers, those things probably seem pretty familiar, if not mainstream. But in the 2015 IRC and the subsequent 2018 and 2021 editions, some more obscure materials and methods were added in new appendix chapters. Historically, the appendices provided guidance for effective use of the main body of the codes, such as sizing gas-pipe, water-distribution, and gas-venting systems. However, in the last two decades they have also become a place to recognize less common and perhaps more controversial subjects and methods of construction. Unlike the main body of the code, appendix chapters are adopted individually. They provide broadly accepted standards but aren’t things that everyone everywhere is likely to be familiar with or that jurisdictions want to allow—such as tiny homes, for which an appendix first appeared in 2015.

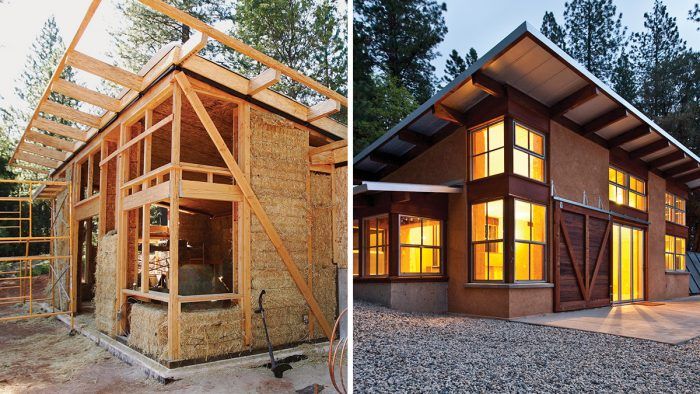

Two other appendices added that year—R and S—offer construction methods that are probably a bit unfamiliar even to this magazine’s audience: light straw clay (now Appendix AR in the 2021 IRC) and straw bale (Appendix AS). Though these chapters are relatively new to the code, the methods aren’t new to the world. Americans have found effective shelter in straw-bale structures since at least the late 1800s, following the invention of the hay baler. The method gained popularity in the back-to-the-land days of the 1960s and ’70s, when people with no conventional building experience wanted DIY options to build on the cheap using local, abundant materials. Today there are straw-bale structures in every U.S. state and all over the world, and the material is a favorite of many natural and some high-performance builders.

As a challenge to its widespread acceptance, straw construction is often belittled as building a house with animal food—though this is patently false. Unlike hay, which is grown to feed livestock, straw is what’s left after harvesting grain. Section AS103.7 requires the straw to be specifically from wheat, rice, rye, barley, or oat. In all cases, the straw is essentially just unprocessed cellulose, and the straw’s tubelike structure can create walls with R-values much higher than those found in conventionally framed houses, depending on the size and orientation of the bales.

Appendix AS illustrates two common straw-bale construction systems—load-bearing, and post-and-beam with straw-bale infill—though other methods can be permitted if approved in the jurisdiction. In the infill system, the straw simply fills the space between the frame’s timbers and provides a surface for the finish, which is typically plaster-applied right to the bales. In the load-bearing system, the plastered straw-bale walls themselves carry vertical loads. There are also provisions for straw-bale braced wall panels; the plaster applied on the inside and outside of bale walls can act as a load-resisting skin, much like sheathing attached to studs or an SIP wall with sandwiched insulation. Under limited design conditions and with specific details, plastered straw-bale walls can resist in-plane lateral wind and seismic loads.

For vertical load-bearing designs, the skin is also doing the work. Though the bales themselves support top plates to pick up the roof load, the load gets transferred to the plaster skins. The bales must be compressed with a uniform load not less than 100 lb. per lineal ft. before the plaster is applied. These skins must bond directly to the bales, and the plaster must be continuously supported at the base of the wall to transfer the loads to the foundation or other supporting structure. (Weep screeds here are a no-no.) These skins are not to be equated with any typical plaster “finish” supported by a wall. Here, the plaster is a structural component.

There are many specific details in this section for bale size, plaster type and thickness, and plaster reinforcement, to name a few. There’s one more detail I want to call out, though: the allowance for a “truth window.” Straw-bale walls have to be finished to provide protection from weather and physical damage, as well as fire resistance and to restrict the passage of air through the walls. This finish is supposed to be continuous, with one small exception for a hole (covered with a door or panel) to provide a window to show off what your walls are really made of. The IRC knows this somewhat unusual method of construction is something we would want to show off.

Light straw-clay is a whole other animal, utilizing loose straw that is lightly coated in wet clay and then tamped into forms to fill the space between structural members and supports. Germans have used this method, or variations of it, since at least the 1100s in half-timbered homes. The IRC allows light straw-clay only for nonbearing infill walls but does provide methods for braced wall panels utilizing a plaster skin like that used in straw-bale construction.

Both of these new appendix chapters were fine-tuned in the 2018 edition, and they seemingly opened the door for more alternatives. In 2021, the IRC added Appendix AU, which addresses cob construction. This method dates back thousands of years, with variants found around the world, including the southwestern United States and England.

The term “cob” is derived from an Old English word for “lump,” because this is historically a method of shelter built using hand-formed clods of high-clay soil and straw stacked and pressed together. The modern method is described in 16 pages of prescriptive provisions for nonbearing and bearing walls, as well as braced wall panels. A design advantage for cob construction is the ease of constructing walls of various angles or with curves, and the IRC appendix provides useful methods for providing non-rectilinear braced wall lines.

Two more modern ideas were also included in the 2021 IRC: Appendix AW provides just over a page of guidance for 3D-printed buildings, and Section R301.1.4 recognizes the use of intermodal shipping containers as a structural system for construction.

Building codes have been evolving for centuries, but shelter has been evolving since the dawn of humankind. The continued three-year revisions of modern model codes represent the present-day expectations of society, whether that involves fine-tuning a common practice with new knowledge; responding to a new or emerging technology, style, or material; or reevaluating methods of the past. Codes are created to follow the will of society, so be sure to contribute to that will. Proposals for the 2024 IRC are being reviewed by committees this year (proposed appendixes for hemp-lime construction, extended-plate wall construction, and accessory dwelling units are under debate as I’m writing this), with opportunities to be provided for public comment this summer and additional hearings this fall. Most folks get involved through an organization, but many individuals attend and participate.

Glenn Mathewson is a consultant and educator with BuildingCodeCollege.com.

From Fine Homebuilding #307

RELATED STORIES

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A House Needs to Breathe...Or Does It?: An Introduction to Building Science

Code Check 10th Edition: An Illustrated Guide to Building a Safe House

The New Carbon Architecture: Building to Cool the Climate