PVC for a Rot-Proof Fence

Built with rot-proof material with traditional tools and techniques, this classic border is engineered to never sag.

Synopsis: Jeff Nixon is an avid woodworker, but he decided to build his most recent project—a privacy fence around his property—with PVC. The material is rot-proof, low-maintence, and able to be cut with woodworking tools. In this article, he explains step by step the process of installing the PVC pipe posts, building the three-part posts sleeves, and putting together the two-part fence-panel sections. Detail drawings show the dimensions and connections of the posts and fence panels.

After building two additions on our home in Munster, Ind., a suburb of Chicago, and after years of other projects around the house, it was finally time to build the fence I had designed many years ago. I have been an avid woodworker my entire life and in addition to major remodeling projects I have built our kitchen cabinets, doors, coffered ceiling, and much of the furniture in our home. I have even taken on a few commissioned pieces. So, while the notion of building a wood fence seemed natural, I wasn’t crazy about the idea of peeling paint or providing dinner for pesky insects and rot, nor was I keen on working with the bowing, cupping, twisting, and warping, which seems to be the dominant characteristics of exterior-grade lumber these days. All things considered, a PVC fence made the most sense.

While my budget had limits, it wasn’t my primary concern. If it was, I would not have chosen PVC. Compare the price of a 12-ft. 1×10: PVC at $78, cedar at $70, and pressure-treated wood at $20. Just like most building materials, the price of PVC has gone way up. At the time of writing this article, it costs about 30% more than when I started this project. Right now, each one of these fence posts would cost approximately $330 to build, and each fence section about $780. Of course, that’s the up-front price. Because PVC lasts so long with little or no maintenance, the cost-per-year comparison would likely be a better indicator of overall value. The way this fence is constructed, I’m confident that it will last decades with no more than the occasional pressure washing.

I’ve been a creative director in the advertising world for most of my adult life, so design and attention to detail are in my blood. The proportions and aesthetics of this fence were specifically created to complement my particular house. Even if this exact design isn’t the perfect fit for you or your customer, the majority of the cutting, assembly, and fastening tips and techniques apply to nearly all PVC projects. Whatever kind of fence you decide to build, make sure you check on the height and setback restrictions with your local municipality and always call 8-1-1 to have your utilities located before you dig your post holes.

Working with PVC

Most of the components in this fence are made out of 1/2-in.-thick 4×8 sheets of PVC. I also milled parts out of 12-ft. 1×10 PVC trim boards. To make transporting easier, I had the home center rip off an 18-3/4-in. piece for the fence sections and cut other sheets down to 52-1/4 in. for the posts. The PVC pickets and the corner trim on the posts are the only factory parts. While I wanted all the components on both the posts and fence to be smooth, the sheets and the boards are only readily available with a woodgrain texture on one side. To hide the grain, I kept the texture side facing down on the lower parts and had them face up on the trim details above eye level. The sheets, trim boards, and pickets were not all made by the same manufacturer, but they all must use similar manufacturing techniques because I found little difference between them.

I was well-equipped to tackle this project because the same carbide-tipped cutting tools that work for wood also work well for PVC. I wanted clean edges throughout, so I used no factory edges, which were too rough. And in order to keep cut surfaces as smooth as possible, every exposed cut edge on this project was shaved with a block plane. With no knots, splits, or checks to deal with, it was satisfying to produce unbroken, tissue-paper-thin shavings with every pass.

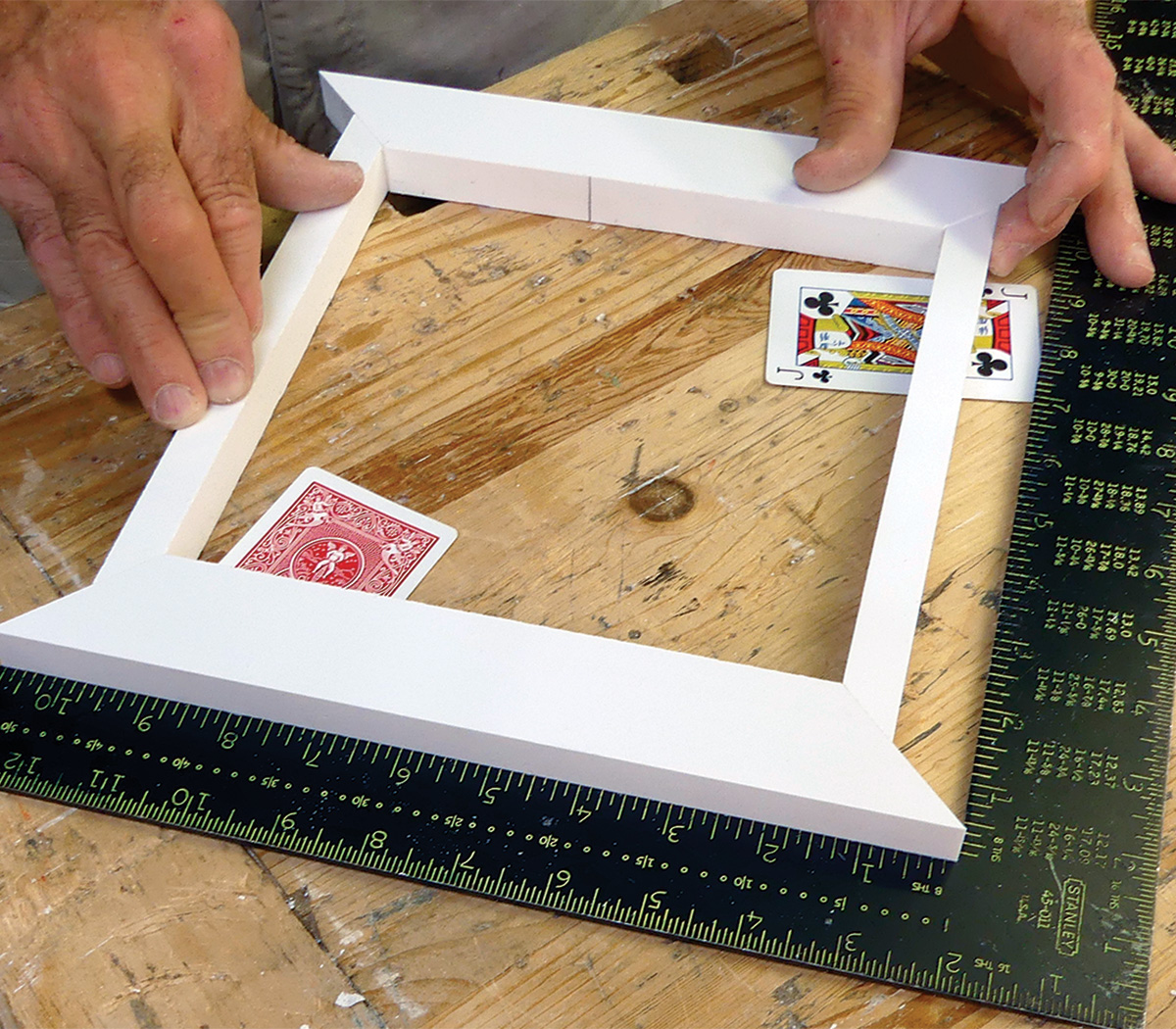

Dealing with the inconsistencies in the width and thickness of PVC was a challenge. When creating a butt joint or miter, it’s not uncommon for two boards to differ in thickness by 1/32 in. Even for an outdoor project like a fence, the difference is noticeable, especially to someone who’s accustomed to cabinetry and furniture-building tolerances. Because the thickness often varies from one end to the other in the same board, I could sometimes get a better match by simply spinning one or both boards around and using the opposite end. On other occasions, I used playing cards to bring the visible side of the connection into plane.

A PVC post will never rot

One of the main purposes of building a PVC fence was to avoid rot, so I decided to use structural posts made out of 4-in. Schedule 40 PVC pipes instead of wood. I started by locating and installing the corner posts first. I then measured the distance between the corner posts and divided the space so that each fence section would be the same size and as close to 9 ft. as possible. I chose 9 ft. mostly for aesthetic reasons having to do with the proportions of the finished post in relation to the composition of the fence sections.

I ran a string between the corner posts to make sure the holes were in a straight line and cut a story pole so that they were all spaced the same distance apart. I dug the holes 10 in. wide and 34 in. deep. I also flared the bottoms to add support and prevent heaving. If a new hole ended up near a hole left behind from an old fence post, I dropped in a concrete-form tube. The holes required about two-and-a-half 80-lb. bags of concrete to fill, and the PVC pipes required an additional one-and-a-half bags. I ran the posts long and trimmed them to height after they were installed, and then filled the inside of the pipes with concrete.

I decided to build a water level to locate the top height of the posts. I could have used a laser, but a water level is just as accurate, is fun to build and use, and does not require clear sightlines, which was a bonus given the dense vegetation in parts of my yard. I made the stand from scrapwood and T-nuts, and the level is nothing more than 75 ft. of 3/8-in. tubing, a barbed splicer adapter fitting, and a water reservoir made out of an animal cracker container from Costco. My yard is relatively flat, so only two different heights were needed for the entire run of fencing. I marked a reference line with a pencil on the side of my house that I used to re-calibrate the level for every batch of poles that needed trimming.

Cementing connections

To avoid the purple mess, I decided not to use primer, but I’ve worked with enough PVC in the past and have done enough research to feel confident that every joint on this project will hold up as long as the PVC itself. I refer to the process of using PVC cement as “gluing” for the purposes of this article, but it’s really more accurate to call it “solvent-based welding.” The PVC holds together well and has no end grain, so you can create strong joints that you could never pull off with wood. This also translates into an amazingly small amount of waste, which is beneficial for both the budget and the local landfill.

When working with any PVC cement, eye protection is important, and wearing a HEPA- and vapor-rated respirator is absolutely essential. I would also recommend installing a fan in a window or working outdoors whenever possible.

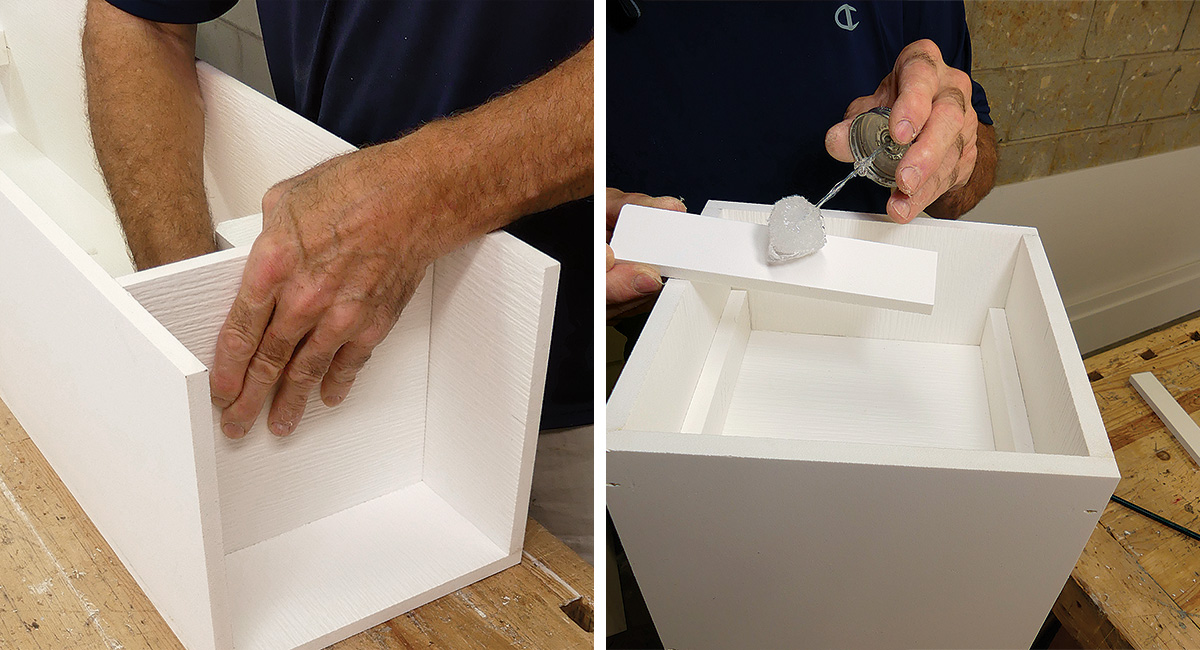

You have to be prepared and move fast when working with PVC cement, and it helps to work out of a full can. I constantly combined cans to create full ones. At first, I used Oatey Heavy Duty Clear PVC Cement on every connection because of its superior holding power, but eventually I started using PVC TrimWelder (slow cure) to give myself more working time on the larger glue-ups. With that large applicator, it’s all too easy to get cement where you don’t want it. Even though it’s clear, excess cement has a noticeable sheen and creates smudges if smeared with a dirty finger, so I kept a roll of paper towels on hand to wipe squeeze-out, drips, and dribbles as fast as possible. If I missed a spot and the cement started to set, I would wait for it to dry and scrape it off with a razor blade. I also found that Mr. Clean Magic Erasers work well for removing grimy fingerprints and general blemishes.

This fence build required a lot of planning, time, and energy, and I’m happy with how it turned out. Though it’s been finished for a while, when I pull up the driveway or glance out a window, I’m still surprised at just how much it has enhanced our entire property.

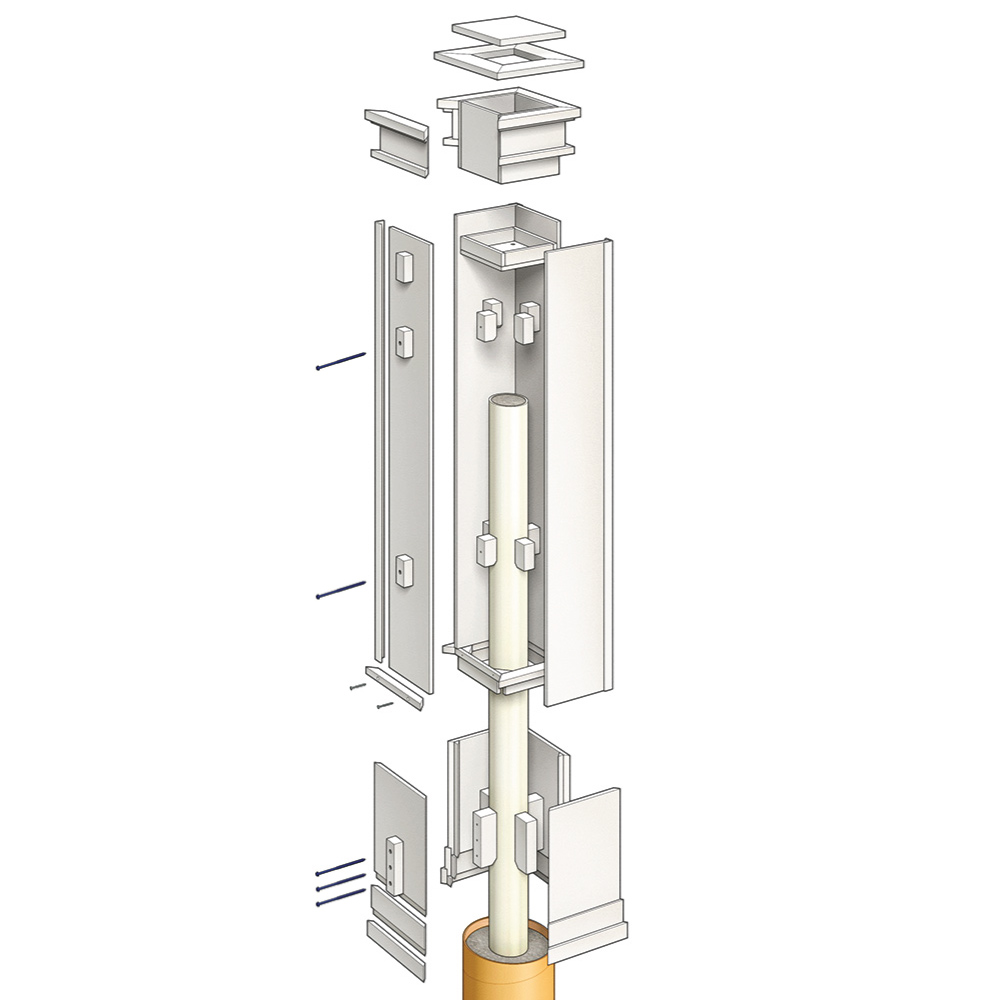

A Three-Part Sleeve Mimics Traditional Post Design

Build the post base

Building and handling the post sleeves is easier to do in sections, so each post is made up of three parts: a base, a middle, and a cap. There are support blocks on the inside of the base and middle that secure it to the structural post and keep it plumb. There are also fence-rail support blocks on the outside of the base and middle that hold up the fence sections. The bases do not rest on the ground, but are held to the concrete-filled PVC support posts with long concrete screw anchors, ten per post. The screws pass through both the post support blocks and the fence-rail support blocks.

Build the middle section

This middle section is friction-fit into the post base with flanges, and the flanges are glued in place using the base as a guide. Glue only three of the middle section panels together at first; the last panel is dry-fit in place so that the structural-post support blocks can be fine-tuned to fit around the post. In order to maintain enough clearance to squeeze a fence section between two posts, two sides of the astragal trim and two corner moldings need to be installed after the fence sections are set in place.

Build the cap

Like the middle section, the cap is friction-fit into the section below it. To achieve the exact proportions I was after, I found it necessary to create custom widths for a couple of these trim details, but the post top is the only section on this whole project that contains parts that are not made from 3⁄4-in. or 1⁄2-in. stock or preformed components.

Install the middle section and the post base

In order to keep the post sleeves in line, I took the straightest 10-ft. 2×4 I could find and ran it over a jointer, then ran it through a planer. I held it against the face of two adjacent posts until it lined up flat on both surfaces. The finished sleeves are held to the structural posts with masonry screw anchors.

A Two-Part Panel Prevents Sag

Build the bottom rail

To get the exact length of the fence sections, I measured the distance between the installed post sleeves. These sections are more than 8 ft. long, so the boards that run the full length need to be assembled from multiple pieces. And since PVC does not have the same structural integrity as a dense hardwood, I checked with the manufacturer, who was kind enough to have experts take a look and approve both my truss design and overall assembly approach.

Assemble the pickets and upper panel

Because I took the time to make sure the support posts were the same distance apart, I was able to figure out the picket spacing ahead of time, which meant that all I had to do was find the exact center of the upper rails and then I could be confident that the picket spacing on each end worked out the way I wanted.

Being able to plow the dadoes into six rail sections at once was a huge time saver. Getting this done required two router jigs. The first jig is only used to create the center dado. The second jig has a guide board attached to the bottom that fits into that first dado and all the subsequent dadoes. I used a finished rail as a spacing guide while fastening the pickets.

In order to fasten the pickets to the exact center of the picket support board, I cut spacers to lay the pickets on and had to place shims under a rail. Using a large table makes this fence section assembly process a lot easier.

Install the complete panel

You will need an extra set of hands to lift the fence sections because they’re heavy, but if your measurements and cuts were accurate, each section should slide into place with little effort. Because the bottom rail is fully supported by the rail support blocks, I decided adding screws was not necessary. I fastened the upper rails to the rail support blocks with the FastenMaster Cortex Hidden Fastening System, which didn’t require predrilled holes and came with PVC plugs that match perfectly.

Jeff Nixon is a freelance art director. Photos by Mark Petersen, except where noted. Drawings: Christopher Mills.

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

While I applaud the care of layout and detailing that you have done, I would highly encourage a rethinking of using PVC as a building material, especially when careful detailing and construction of a wood (or other natural product) fence can yield a beautiful and long lasting result (especially in such capable hands) without using as many harmful chemicals.

Polyvinyl Chloride, commonly abbreviated PVC, is the world’s third-most widely produced synthetic plastic polymer. PVC is largely used in construction because it can be more effective in weight, cost, and performance than traditional materials such as copper, iron or wood in pipe applications.

• The production of PVC results in the release of toxins including dioxins. The burning of PVC results in the release of dioxins. Additives of PVC can be toxic to users. The manufacturing and incineration of PVC also creates and releases dioxins, which cause a wide range of health effects including cancer, birth defects, diabetes, learning and developmental delays, endometriosis, and immune system abnormalities. One type of dioxin present in PVC is the most potent carcinogen ever tested. These toxin’s primary pathway into the human body is through inhalation.

• The chemicals present in PVC are known as persistent bio-cumulative toxins (PBT’s) which mean they will persist in the environment and species around the world indefinitely. These are also commonly referred to as “forever chemicals.” PVC never completely breaks down in the environment, it cannot be recycled and interferes with the recycling of other plastics.

Thanks,

Jake LaBarre, AIA

architect, builder, and educator.

The source for my information is linked below

https://healthybuilding.net/uploads/files/environmental-impacts-of-polyvinyl-chloride-building-materials.pdf

Great comment. Thanks for the link and the education. I honestly thought this article was an elaborate FHB April Fool's joke: lifelong woodworker builds a plastic fence.