Air-Sealing SIP Seams

Houses built with structural insulated panels require unique methods of air-sealing to ensure an airtight thermal envelope.

Structural insulated panels (SIPs) are large building components made of rigid foam (either expanded polystyrene or polyisocyanurate) faced on both sides with oriented strand board (OSB) that are used as floors, walls, and roofs. The panels usually include 2x lumber captured between the OSB around the perimeter and are typically joined at the seams with splines and screws. Wherever there is a seam in a home’s thermal envelope—between a window and a rough opening, or between a concrete foundation and the mudsill, for example—there are opportunities for air leakage. SIP seams aren’t exempt from leakage, so they must be air-sealed carefully. Air leaks through SIP seams can lead to rot or, in extreme cases, catastrophic structural failure.

Manufacturers’ recommendations

Most SIP manufacturers recommend that builders seal panel seams with multiple beads of caulk and canned spray foam. Some manufacturers also specify the use of foam gaskets in some locations. According to “Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs) Seams,” a web-based guide from the Building America Solution Center, “The wall-floor, wall-wall, and wall-roof seams can each require as many as six beads of caulk, and the roof-ridge seam can require up to eight beads of caulk…Consider using a power caulker; even in a small (1200 sq. ft.) home, the amount of caulk required can total over 5000 lin. ft. of caulk.”

Recommended sealing methods vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, especially with regard to the use of caulk and foam gaskets. Many SIP manufacturers provide a routed channel designed to receive spray foam. Some provide foaming holes, while other manufacturers advise builders to drill a series of 3/8-in. holes (usually spaced about 8 in. to 12 in. apart) at SIP seams, a method called “drill and fill.”

Until relatively recently, the use of caulk and spray foam satisfied the requirements of most SIP manufacturers. However, in 2001, a cluster of SIP failures in Juneau, Alaska, highlighted problems with SIP sealing methods. Juneau’s failing SIPs had OSB rot near panel seams; investigators concluded that air leaks through poorly sealed seams allowed the condensation of moisture from the exfiltrating air.

The Juneau failures showed that SIP seams sealed with spray foam don’t always remain airtight. Among the possible factors explaining these leaks: The weather conditions may have been damp or cold on the day that the seams were sealed, the workers may have been sloppy, or the panels may have moved due to the settling of the building or to humidity changes. Finally, there is some evidence that thin layers of spray foam aren’t always airtight.

After the Juneau failures, most SIP manufacturers began recommending the use of interior tape in addition to caulk and spray foam. SIP installers who followed this recommendation noticed an unexpected side benefit: The use of interior tape appears to have eliminated the problem of shingle ridging. (In the past, some SIP homes had visible ridges in their asphalt roof shingles above every roof-panel seam.)

Sometimes the tape needs to be installed before the SIPs

To seal interior seams, SIP contractors use a high-quality tape such as Siga Sicrall, Siga Wigluv, or R-Control SIP tape. Taping SIP seams can be tricky, though. For example, when SIPs are installed over a timber frame, the timbers sometimes conceal the seams. The tape is then draped sticky-side up, with the paper backing left on the tape. Once the panels have been installed, the paper is peeled back and torn away so the tape can adhere to the OSB facing of the SIPs on each side of the beam.

After the shell is complete, it’s always a good idea to verify the tightness of SIP seams with a smoke pencil while a blower door is depressurizing the building.

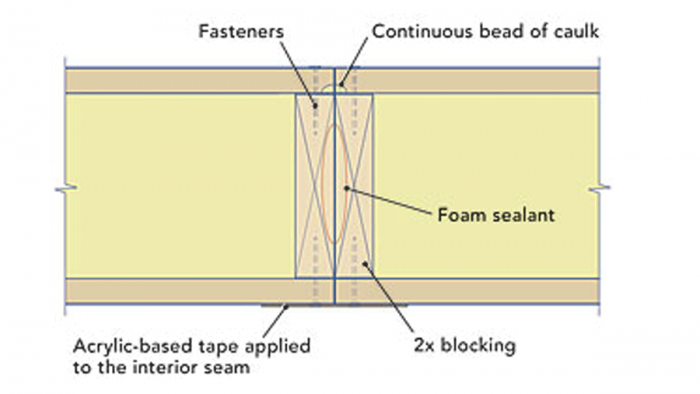

Seal the panel seams

Most SIP manufacturers now recommend a belt-and-suspenders approach to seam sealing that includes spray foam applied between the panels, a continuous bead of caulk applied to the exterior seam, and acrylic-based tape applied to the interior side of the panel seam.

A tricky but necessary tape detail

When the seam of a roof panel runs along or across a wide beam, installers need to drape a wide piece of peel-and-stick acrylic-based tape, with the paper of the sticky side facing upward, over the beam before the panels are set. As soon as the panels are installed, the paper backing can be torn away and the tape sealed to the panel on each side of the beam.

Detailing the ridge

At the ridge, roof panels can be mitered or overlapped. In either case, the interior side of the seam between the panels should be sealed with tape. Exterior gaps are filled with expanding foam.

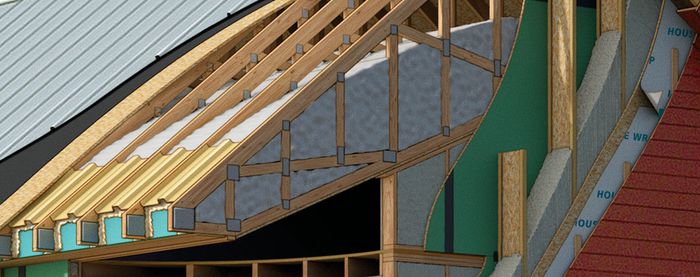

Venting a SIP roof for asphalt singles

Most asphalt-shingle manufacturers prohibit the installation of their shingles on unventilated roofs. The easiest way to add ventilation channels to a SIP roof is to install 2×4 furring on the panels, then install the roof sheathing over the furring strips.

Do SIP roofs need to be vented?

There are two ways to design a SIP roof. Contractors who install a so-called hot roof (an unventilated roof) fasten the roofing underlayment and roofing directly to the OSB facing of the roof SIPs.

The second type of roof, a so-called cold roof, features ventilation channels above the SIPs and OSB or plywood sheathing over the channels. Ventilation channels add to the cost of a SIP roof, but they provide several benefits. Most asphalt-shingle manufacturers void their warranties when shingles are installed on an unventilated roof. In snowy climates, ventilation channels reduce the chance of ice-damming problems. Finally, if any roof-panel seams develop air leaks that permit condensation, ventilation channels will help dry out the damp OSB, reducing rot. (To ensure that these ventilation channels do their job, it’s important to specify a vapor-permeable roofing underlayment such as asphalt felt.)

“I built timber frames in the ’70s and ’80s and, like most other framers, we did not vent the roofs,” writes Bob Irving, a New Hampshire contractor who posts comments on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com. “Every manufacturer I’ve spoken to (major in terms of the New England market at least) said they recommended the practice [of venting roofs] in their manuals. No manufacturer that I’m aware of ever mandated the practice.” Irving continues, “Since then, I have repaired several SIP roofs where the OSB has rotted.”

In short, if you are interested in reducing the chance that your roof SIPs will develop rot, ventilation channels are a good investment.

Drawings: Dan Thornton

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Flashing Boot Repair

Peel & Stick Underlayment

Shingle Ripper