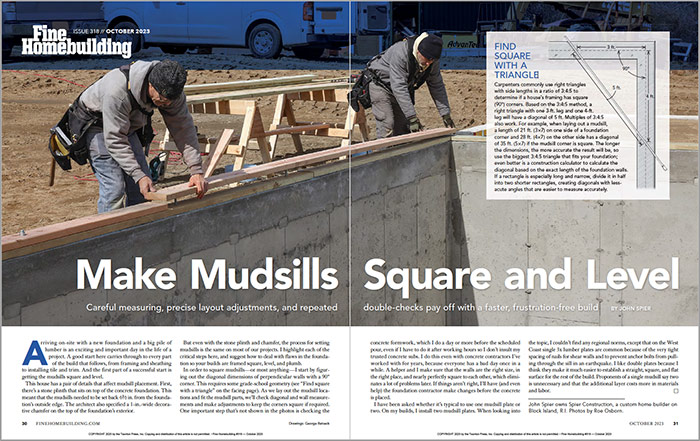

Make Mudsills Square and Level

Careful measuring, precise layout adjustments, and repeated double-checks pay off with a faster, frustration-free build.

Synopsis: In this article, builder John Spier shares his process for installing a mudsill. He begins by checking to see if it is level, square, and in plane. If it isn’t, he makes the necessary correction. From there he locates the placement of the mudsills and snaps layout lines. He then installs the mudsill, which in his area is made of two 2×6 plates.

Arriving on-site with a new foundation and a big pile of lumber is an exciting and important day in the life of a project. A good start here carries through to every part of the build that follows, from framing and sheathing to installing tile and trim. And the first part of a successful start is getting the mudsills square and level.

This house has a pair of details that affect mudsill placement. First, there’s a stone plinth that sits on top of the concrete foundation. This meant that the mudsills needed to be set back 6-1⁄2 in. from the foundation’s outside edge. The architect also specified a 1-in.-wide decorative chamfer on the top of the foundation’s exterior.

But even with the stone plinth and chamfer, the process for setting mudsills is the same on most of our projects. I highlight each of the critical steps here, and suggest how to deal with flaws in the foundation so your builds are framed square, level, and plumb.

In order to square mudsills—or most anything—I start by figuring out the diagonal dimensions of perpendicular walls with a 90° corner. This requires some grade-school geometry (see “Find square with a triangle” below). As we lay out the mudsill locations and fit the mudsill parts, we’ll check diagonal and wall measurements and make adjustments to keep the corners square if required. One important step that’s not shown in the photos is checking the concrete formwork, which I do a day or more before the scheduled pour, even if I have to do it after working hours so I don’t insult my trusted concrete subs. I do this even with concrete contractors I’ve worked with for years, because everyone has a bad day once in a while. A helper and I make sure that the walls are the right size, in the right place, and nearly perfectly square to each other, which eliminates a lot of problems later. If things aren’t right, I’ll have (and even help) the foundation contractor make changes before the concrete is placed.

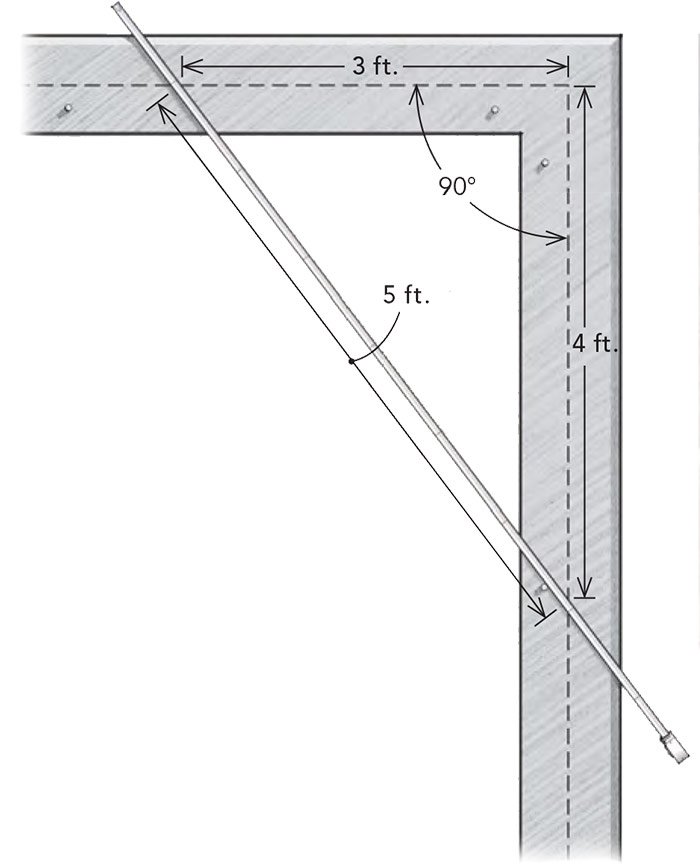

Find Square With a Triangle

Carpenters commonly use right triangles with side lengths in a ratio of 3:4:5 to determine if a house’s framing has square (90°) corners. Based on the 3:4:5 method, a right triangle with one 3-ft. leg and one 4-ft. leg will have a diagonal of 5 ft. Multiples of 3:4:5 also work. For example, when laying out a mudsill, a length of 21 ft. (3×7) on one side of a foundation corner and 28 ft. (4×7) on the other side has a diagonal of 35 ft. (5×7) if the mudsill corner is square. The longer the dimensions, the more accurate the result will be, so use the biggest 3:4:5 triangle that fits your foundation; even better is a construction calculator to calculate the diagonal based on the exact length of the foundation walls. If a rectangle is especially long and narrow, divide it in half into two shorter rectangles, creating diagonals with less-acute angles that are easier to measure accurately.

I have been asked whether it’s typical to use one mudsill plate or two. On my builds, I install two mudsill plates. When looking into the topic, I couldn’t find any regional norms, except that on the West Coast single 3x lumber plates are common because of the very tight spacing of nails for shear walls and to prevent anchor bolts from pulling through the sill in an earthquake. I like double plates because I think they make it much easier to establish a straight, square, and flat surface for the rest of the build. Proponents of a single mudsill say two is unnecessary and that the additional layer costs more in materials and labor.

Check the Foundation

This house has a “T”-shaped gable roof with a pair of valleys. For the rafters to work out, the house has to be framed perfectly square. If the foundation contractor did a good job, all the final dimensions should be within 1⁄2 in. of those specified in the plan. If not, you or someone else will need to make corrections for a smooth build (see “Problem-foundation fixes” below).

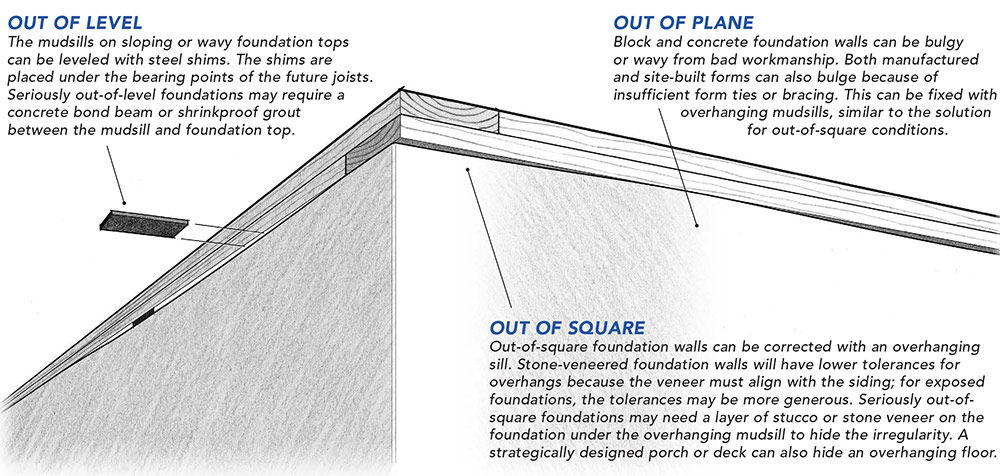

Problem-Foundation Fixes

The foundation contractors I work with on Block Island are skilled and experienced, but like other home-building trade workers, concrete foundation contractors are scarce in many places and the work can reflect the relative inexperience of folks who are learning on the job. Wall lengths and placement that are way off their marks are ultimately going to require adjustments to the floor plan. These are a rarity, as multiple people involved in the build would have to neglect checking the wall locations. I’ve heard of foundations that are as much as 3 in. out of level or square. I’d suggest contract language that specifies that the foundation will be within 3⁄4 in. of square and within 1⁄2 in. of level. If your foundation is not as square or as level as this, you can use these strategies to get things on track.

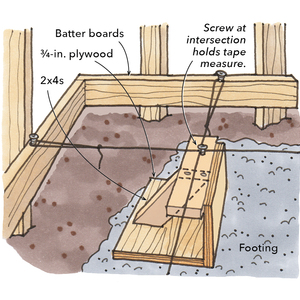

Locate the Mudsills

For this project, I chose the longest wall and its opposite as the starting point. When I’m locating mudsills, I don’t accept anything less than perfect for the layout, because errors will accumulate as the house goes to the second and third levels. If the diagonal measurements are off at all, I adjust the layout by moving the plate location slightly and then rechecking the diagonals. I do this as many times as necessary to ensure the corner of the building is square.

Snap Layout Lines

With the corner points located, we snap preliminary layout lines using nonpermanent blue chalk so that we can erase lines if tweaks need to be made. When we’ve snapped all four walls, I check that the opposing diagonals are the same, indicating that the equal-length walls are square to each other. Then, I turn my attention to laying out the sills for shorter walls for any jogs, wings, or bays. This project had jogs for two porches. If you find that small rectangular sections cannot be made square to the main rectangle, you can slightly rotate the main rectangle on the foundation to make the smaller sections fit better.

Set the Sill Plates

The Bottom Plate

In our area, we install two mudsill plates, usually 2x6s, with the lower one made of pressure-treated lumber. These plates receive holes drilled to fit over the foundation’s anchor bolts, and are then set on top of a foam sill seal. The sill seal prevents air leaks between the foundation wall and the mudsill and acts as a capillary break between the foundation and mudsill. Before I start installing plates, I check the anchor bolts to make sure they are within an inch of the centerline of the plate layout, and placed high enough to fully thread a washer and nut over the plates. If one or more are significantly off, we cut them off with a reciprocating saw and drill a hole into the top of the foundation with a rotary hammer a few inches away from the cut bolt. We then clean the hole with a brush and compressed air and install an 8-in. length of high-strength threaded rod with epoxy adhesive.

Two Remedies for High Spots in the Foundation

Almost no foundation is perfectly flat. There are always places where the concrete settles a little or the forms shift, or the finishers miss their height marks by just a little. How I level the mudsills depends on how bad the imperfections are. If there are just a couple of high spots, I plane the plate or grind the raised spots. If there are low spots, I fill them in with nonshrink grout, which slows the work while we wait for it to set. Don’t level the mudsills with cedar shims, which compress, causing future problems, especially where there are point loads.

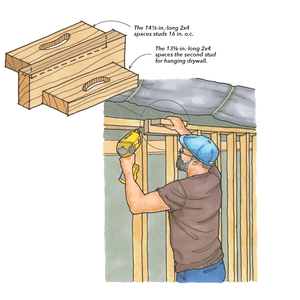

The Top Plate

The pressure treated mudsill bottom plate is usually wider than the other plate stock, and most sills are laid out from the inside dimensions. Allow for the PT’s extra thickness, or you’ll end up with a flare at the bottom of your wall sheathing.

From Fine Homebuilding #318

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

RELATED STORIES

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Bluetooth Earmuffs

Stabila Extendable Plate to Plate Level

Smart String Line