The Pros and Cons of Spray-Foam Insulation

The most important thing isn't necessarily what insulation material you choose, but that you get the installation right.

Though it seems like a product that has evolved quickly in recent years, insulation hasn’t changed all that much. For example, mineral wool had a resurgence in popularity, but mineral wool has been around for a long time. Manufacturers are just doing a better job of marketing their products and progressive builders are continuing to try to make the most high-performing and least-harmful materials work in their homes. In other words, there’s a lot to know about insulation.

Not only that, but builders are using materials in new ways and in combination. Flash-and-batt installations, which use both spray foam and fiberglass (or other) batts, are an example of how builders are leveraging the strength of different types of insulation. The most important thing isn’t necessarily what material you choose, but that you get the installation right.

All insulation needs to be installed right to work. This is equally true for fiberglass batts and spray polyurethane foam. The latter has a lot of benefits that make you wonder why a builder would choose anything else. Well, let’s take a look at one of the ways it’s reputation gets tarnished, poor installation, and see if we can help ensure a successful spray foam installation, should you choose to use it on a project.

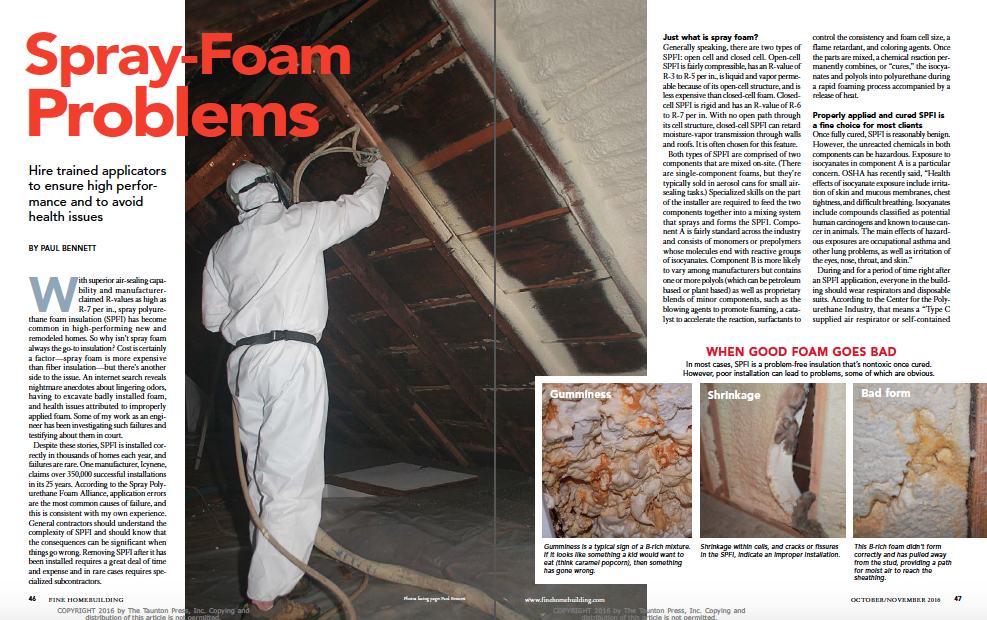

With superior air-sealing capability and manufacturer claimed R-values as high as R-7 per in., spray polyurethane foam insulation (SPFI) has become common in high-performing new and remodeled homes. So why isn’t spray foam always the go-to insulation? Cost is certainly a factor – spray foam is more expensive than fiber insulation but there’s another side to the issue. An internet search reveals nightmare anecdotes about lingering odors, having to excavate badly installed foam, and health issues attributed to improperly applied foam. Some of my work as an engineer has been investigating such failures and testifying about them in court.

Despite these stories, SPFI is installed correctly in thousands of homes each year, and failures are rare. One manufacturer, Icynene, claims over 350,000 successful installations in its 25 years. According to the Spray Polyurethane Foam Alliance, application errors are the most common causes of failure, and this is consistent with my own experience. General contractors should understand the complexity of SPFI and should know that the consequences can be significant when things go wrong. Removing SPFI after it has been installed requires a great deal of time and expense and in rare cases requires specialized subcontractors.

Just what is spray foam?

Generally speaking, there are two types of SPFI: open cell and closed cell. Open-cell SPFI is fairly compressible, has an R-value of R-3 to R-5 per in., is liquid and vapor permeable because of its open-cell structure, and is less expensive than closed-cell foam. Closed cell SPFI is rigid and has an R-value of R-6 to R-7 per in. With no open path through its cell structure, closed-cell SPFI can retard moisture-vapor transmission through walls and roofs. It is often chosen for this feature.

Both types of SPFI are comprised of two components that are mixed on-site. (There are single-component foams, but they’re typically sold in aerosol cans for small air sealing tasks.) Specialized skills on the part of the installer are required to feed the two components together into a mixing system that sprays and forms the SPFI. Component A is fairly standard across the industry and consists of monomers or prepolymers whose molecules end with reactive groups of isocyanates. Component B is more likely to vary among manufacturers but contains one or more polyols (which can be petroleum based or plant based) as well as proprietary blends of minor components, such as the blowing agents to promote foaming, a catalyst to accelerate the reaction, surfactants to control the consistency and foam cell size, a flame retardant, and coloring agents. Once the parts are mixed, a chemical reaction permanently combines, or “cures,” the isocyanates and polyols into polyurethane during a rapid foaming process accompanied by a release of heat.

For photos and information on how to prevent spray-foam problems, click the View PDF button below.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Nitrile Work Gloves

Great Stuff Foam Cleaner

Staple Gun

View Comments

We had Icynene brand open cell foam applied to out attic and second floor bedroom that has no attic space. Our contractor left no mess what so ever, there was no odor after the first 24 hours except in "dead spaces" like closets. I am thrilled beyond belief, noises that we would hear on windy days were gone, the attic runs 55 - 60 in middle of the winter weather here in Western MA, no ice dams and although we heat our 3500 square foot house with an OWF, my wood consumption is down. The only thing to be aware of is that with less air leakage the moisture content of you house will go up. You may notice more condensation on windows than pre-spray foam. We had a great local contractor with a great crew that did a great job. I highly recommend spray foam but I agree, anyone can buy the equipment and materials, only proper training by the manufacturer can ensure proper application.

Hi Pete, this article is super helpful! We have recently started our new family insulation business and came across this article. Really appreciate you taking the time to educate us all on this. Air sealing with open cell spray foam is not an exciting topic to write about, but you did a great job keeping it entertaining and not boring. Thanks a ton!

Can check us out on htttps:www.sfiprosflorida.com if you get the chance, cheers