Anchoring Wood to a Steel I-Beam

Forget about packing the web; fasten wood to the top, and hang the floor framing with top-mount joist hangers.

Synopsis: Steel beams can carry much more weight than solid or engineered lumber, so they’re often used in home building. But anchoring wood to steel can be time-consuming. John has replaced the most common method — packing the web with lumber — with a far faster method incorporating top-mount joist hangers. By bolting a piece of lumber to the top flange of the I-beam and nailing the joist hangers to it, you can reduce the amount of lumber you use, the number of holes you drill, and the number of bolts you install. And top-mount joist hangers require fewer nails, too.

Modern floor plans are trending toward wide open spaces. Despite advances in engineered-wood beams, there are times when something stronger is needed. Many carpenters shy away from steel because fastening lumber to steel can be tricky. Cutting a steel beam on site is even trickier. Sometimes, though, a steel I-beam is the best choice. Structural steel costs less than comparable LVLs, is strong, and is available from local suppliers. If you order it to the right size with fastener holes punched, your only challenge will be attaching the lumber.

Steel has a few limitations

Although a piece of steel carries a larger load over a longer span with less depth than any other building material, steel has some disadvantages. First, it’s very heavy. You need to make sure you can get it to where it needs to go, either with humans or with a machine. Second, you won’t find steel span charts in a codebook; steel usually needs to be sized by an engineer. Steel should be protected from moisture to prevent rust and deterioration. Also, a steel beam will fail much more quickly and catastrophically than an equivalent wood beam in a fire.

Top-mount joist hangers are the most practical

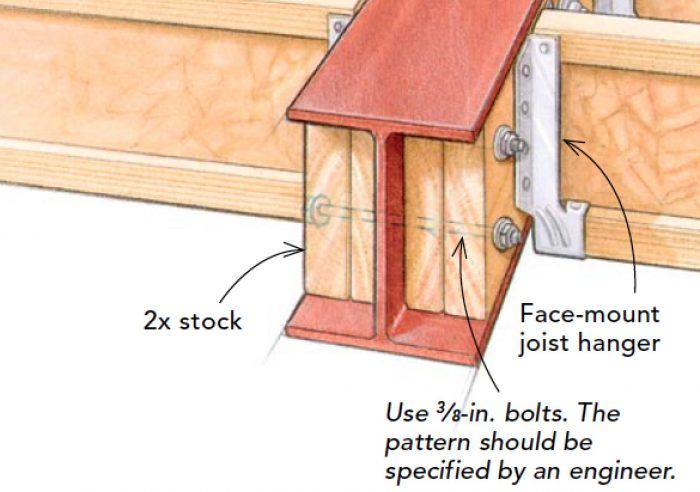

In the simplest usage, an I-beam rests in pockets cast in foundation walls, with floor joists on top of it. More often, though, wood is bolted to the web; then joists or rafters are attached to the wood with standard joist hangers. The drilling and bolting required by this method are so impractical that it’s worth changing before construction. Another attachment method is to weld top-mount hangers to the I-beam. However, this option is rare, not because it doesn’t work but because most framing crews don’t have a welder on site.

I think the best method is to bolt 2x lumber to the top flange of the I-beam, then nail top-mount joist hangers to the lumber. I use 1⁄4-in. by 1 1⁄2-in. lag bolts through the bottom of the top flange. Because top-mount joist hangers won’t resist twisting as well as face-mount hangers, I use strapping below or blocking between the joists. If uplift resistance is needed, I tack the lumber in place with a powder-actuated nailing tool, then through-bolt after the plywood subfloor is down, recessing the bolt heads into the plywood.

The steel I-beams most often seen on job sites are called W- (wide) and S- (standard) shapes, depending on the width of the flange. Steel beams are designated by shape, depth, and weight. For example, a W8x35 beam is a W-shape about 8 in. deep and weighing 35 lb. per lin. ft.

Because steel is hard to cut and drill on site, your supplier needs the exact length along with sketches showing all hole locations and sizes. If you have to cut a beam, an acetylene torch is the easiest method, but metal-cutting blades in circular saws and reciprocating saws work, too.

From Fine Homebuilding #180

From Fine Homebuilding #180

For more illustrations and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Bluetooth Earmuffs

Speed Square

Stabila Extendable Plate to Plate Level

View Comments

Interesting ideas. Two questions: 1) why would steel fail faster in a fire, when it’s non-combustible and fire-resistant - isn’t that it’s advantage, not disadvantage? 2) would downward-driven JH nails driven through 2 x plate on top of steel beam, at 16”-24” have potential to split the 2 x? Seems like every joist is hanging on by 3 nails into outer edges of 2 x plate, a lot of weight outboard of lag bolts seems like it could fail along grain line where JH nails drive into it. I am no expert or pro, just curious. Thanks!

Structural Engineering Services for extensions, loft conversions, load bearing wall removal and structural steel work calculations. At http://www.onlinebeam.co.uk in Surrey we design all Structural works for your home extension project for Building Control Approval. We design concrete foundations, concrete rafts, masonry walls or columns, floors, timber roofs, and steel RSJ beams with full calculations and padstone calcs. We also design steel beam connections and cut splice connections with full calculations and fabrication drawings. We also design timber structures such as floors, flat roofs, pitched roof rafters and purlins, flitch beams, ridge beams all with drawings and structural calculations for Building Approval.

In Friday Night Funkin', https://fnfunkin.io every beat is a chance to shine brighter than ever.