Steel with Wood Framing?

When a wood beam is too big, switching to steel makes sense.

I’m planning a second-story addition for my house, and the builder is saying we need to use a flitch beam in the new floor framing. I was hoping we could use engineered lumber. Bottom line, what are my options?

—Jeremy via email

Structural engineer William Porter, with C.A. Pretzer Associates in Cranston, R.I., replies: A number of design considerations go into deciding what member is right for a job. The top two come from the building codes. First is strength—does the beam have adequate structural capacity for the loads upon it? Next is serviceability—will the member bear those loads without excessive deflection? There are usually other constraints such as schedule, budget, and whether the beam will fit the space, so the right solution for one owner or builder may not fit another.

While complicated to discuss in absolute terms, there are two instances where flitch beams—beams made of plate steel sandwiched between wood—are top options. The first is a flush beam in a floor with dimensional lumber joists. While engineered lumber maintains its cross-sectional dimensions with changes in moisture content, dimensional lumber swells and shrinks. An engineered flush beam paired with dimensional lumber joists that do shrink can lead to a humped floor above or a cracked ceiling below. A flitch beam with a steel plate that’s slightly shallower than its wood members can offer the spans of engineered lumber and move with dimensional lumber to keep everything flat.

Flitch beams can also work well when beam depth and width both matter in terms of fitting other members to or around it, such as ridge beams, structural hips, or structural valleys. In these instances, a flitch beam built up of two plies of dimensional lumber and one steel plate performs similarly to a three- to four-ply engineered- lumber beam of the same depth.

It’s my opinion that there’s almost always a better option than a flitch beam. The plates can be awkward to handle on the job, and flitch plates require lead time for fabrication.

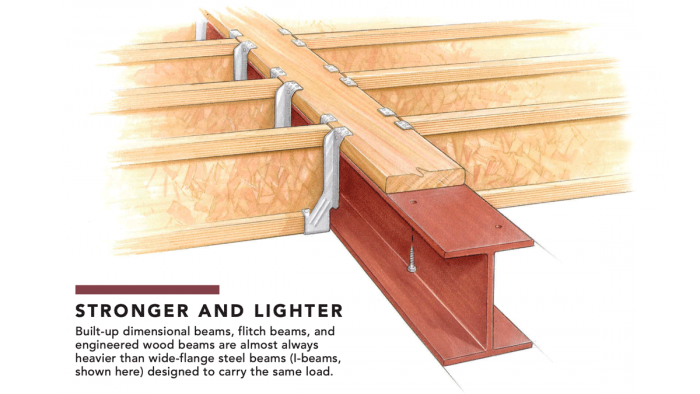

You should also consider wide-flange beams—more commonly called I-beams. The strength and rigidity of a steel member markedly increases if there is more steel closer to the top and bottom of the member. Wide-flange beams put the steel where it counts, in the flanges. I often find that serviceability, not strength, is the governing factor when designing steel members for residential construction. The serviceability of a W10x12 steel beam is nearly identical to that of a 1⁄2-in. by 11-in. steel plate, but the beam weighs only two-thirds of what the plate does. Steel is often priced per pound, so savings in weight means savings in dollars. The wide-flange beam will also be easier to handle since it weighs less, and it has a stable cross-section that can be seated upon supports without high risk of rolling over.

Drawing: Bob LaPointe

From Fine Homebuilding #291

More about steel framing:

What About Steel in Home Construction? – Despite some advantages over wood, light-gauge steel framing hasn’t made the leap to residential building, and the reasons why may surprise you.

Framing With Steel for the First Time – A builder accustomed to wood framing tells about the differences between wood and steel construction.

Old House Journal Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Speed Square

Short Blade Chisel

Protective Eyewear

View Comments

Thanks for sharing this amazing information!! Why don't you check out framing in surrey you might wanna check it out!