Time-Tested Approach to Chimney Flashing

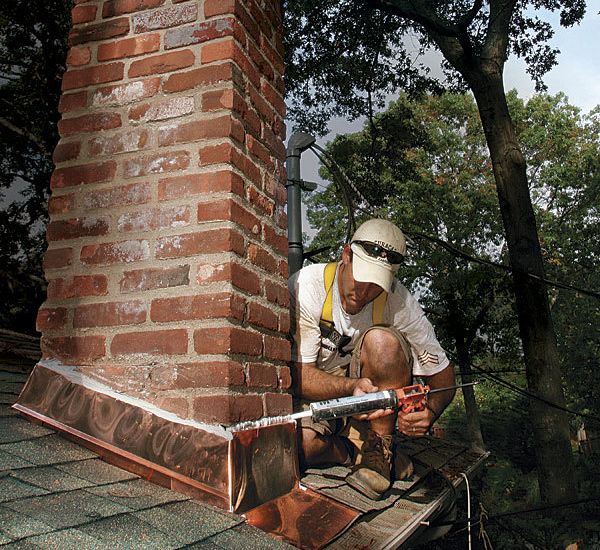

Roofing contractor Dyami Plotke demonstrates how to prepare a chimney for flashing and how to bend, install, and seal metal flashing for a durable, weatherproof, and beautiful job.

Synopsis: Flashing a chimney correctly involves two layers of metal: flashing and counterflashing. In this article, roofing contractor Dyami Plotke explains how he tackles each step in the flashing process. He almost always chooses copper for chimney-flashing jobs because of its appearance, endurance, receptiveness to soldering, and malleability. A series of three detailed drawings demonstrates Plotke’s steps. The first shows where to cut a groove in the masonry for the counterflashing, how to apply a peel-and-stick underlayment over the OSB sheathing patch and up the sides of the chimney, and how to install the apron. The second shows how to install the step flashing and the pan and includes Plotke’s methods for cutting and folding the copper at transition points to make the tightest fit. The third shows how to install the counterflashing. Before sealing the counterflashing to the brick, Plotke uses wedges of folded copper to hold the counterflashing in its groove, and copper pop rivets to connect the counterflashing on the up-slope edge to the counterflashing on the sides. On the up-slope side of large chimneys, he installs a copper cricket to shed water and snow.

By the time my roofing company was called to take a look at the leaking chimney featured here, the sheathing around the chimney was rotten, and the roof rafters beneath were showing signs of water damage.

When the asphalt shingles on this roof were replaced several years ago, the roofer put a new layer of architectural shingles on top of the existing three-tab shingles and reused the house’s original aluminium chimney flashing. He patched several small leaks in the flashing corners with roofing cement, but didn’t touch the flashing otherwise. Had the roofer done a better job with the chimney flashing, the customer would have been spared the headache and expense of replacing the chimney flashing and patching the roof a few years later.

Copper flashing is worth the money

We almost always replace aluminium flashing with copper. Of course, copper costs more than aluminium, but it’s the superior material for several reasons. For starters, it looks good, it lasts almost forever, and it solders great. More important, though, it’s more malleable than aluminium. The flashing pieces can be formed by eye at the metal brake and can be adjusted easily by hand on the roof. When it’s time for new shingles, the flashings and counter flashings can be bent out of the way and repositioned without damage.

Underlayment and apron

The first piece of metal chimney flashing, the apron, is placed on the down-slope side of the chimney. Here, it laps over one three-tab shingle to match the two layers of existing roofing. This shingle is unnecessary when there is only one shingle layer.

Flashing and counter flashing work together

Flashing a chimney correctly involves two layers of water-shedding metal: flashing and counterflashing. The front of the chimney has a single piece of flashing, the apron, as the first layer; the back has a similar piece called the pan. The step flashing, which is the first layer on the sides of the chimney, is made from L-shaped pieces of copper lapped so that they shed water running down the roof. The horizontal leg goes under the shingles, and the vertical goes up the sides of the chimney. Ideally, neither leg is fastened; nail or screw holes compromise the water tightness of the flashing.

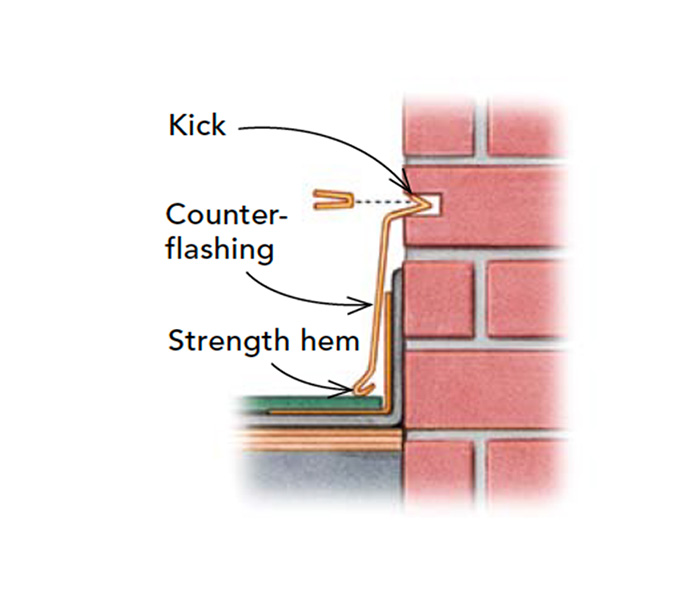

Because there are no nails or screws to hold the vertical leg tight to the chimney, water running down the masonry can get past the step flashing and leak into the house. To prevent this, the flashing’s vertical legs are covered with counterflashing. The counterflashing directs falling rain and water running down the chimney over the first layer of flashing. This creates a finished assembly that looks good and, more important, is watertight.

As was the case on this job, original counter flashings are often installed in a stepped pattern following the mortar lines of the brick. We generally don’t install new flashing in mortar joints. Instead, we cut a 1-3 ⁄ 4-in.-deep groove about 6 in. above the roof deck all the way around the chimney with an angle grinder. Then we install a single piece of counter flashing into the groove.

With this method, there are fewer seams, which translates into fewer potential leaks. It’s also faster and, therefore, less expensive to do it this way. To hold the counterflashing in the groove, we tuck the V-shaped bend at the top into the groove and use small folded pieces of copper to spread the bend, locking the counterflashing in place.

We also rivet the corners with copper pop rivets. These mechanical connections help to hold the counterflashing in place, which in turn helps the sealant at the top of the counterflashing to last up to 20 years.

Step flashing and pan

The apron is cut where it transitions from horizontal to vertical. Then it’s folded around the chimney to prevent winddriven rain and snow from getting behind the step flashing and finding their way into the building. The first piece of step flashing is trimmed so that its bottom leg laps onto the apron.

A quality job is in the details

We give our counterflashing two bends at the bottom, which makes it look and perform better. The lowest bend is called the strength hem. It stiffens the metal and provides a clean, even edge. The upper bend, which also adds strength, is called the kick. The kick breaks surface tension, preventing water from working its way under the counterflashing.

We also make our step flashing from 6-in. by 8-in. pieces instead of the 5-in. by 7-in. pieces commonly found on low-budget roofs. These bigger pieces of step flashing mean fewer leaks from wind-driven rain and heavy snow.

Counterflashing

Counterflashing is what makes step flashing work. The counterflashing pan and apron are made in oversize lengths ahead of time and then cut to length on the roof. A bead of water-block mastic is run under the pan, and a bead of M-1 polyether sealant (chemlink.com) is applied to the top edge of the pan for secondary waterproofing.

Where’s the cricket?

Chimneys that are built anywhere along the rain-carrying parts of a pitched roof (not at the ridges) create a dam that can stop water from draining and allow it to pool behind the chimney. The dam that is created by the chimney can be especially problematic in cold climates, where the chimney can become a collector for snow and ice.

Behind large chimneys, we install a cricket. Shaped like a tiny hip roof, a cricket diverts water and snow around the chimney for better drainage. We install crickets when the chimney is wider than 24 in. (perpendicular to the slope), which is consistent with the shingle manufacturers’ instructions. For smaller chimneys like the one pictured here, a one-piece copper pan is all that’s necessary to carry the roof water around the chimney.

Dyami Plotke is a roofing contractor on Long Island, N.Y.

Photos by Patrick McCombe.

Drawings: John Hartman

From Fine Homebuilding #233

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below:

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Roof Jacks

Fall Protection

Shingle Ripper

View Comments

I was wondering if there is any slope to the copper pan that is installed behind the chimney? My house has a small chimney and I was under the impression that I should install a cricket. After reading this article, I'm now second guessing that. Any advice on the pan would be greatly appreciated. Would it be okay to install a small diverter right above the chimney to help direct water away even more? Thanks so much.